To Cope with My Father's Suicide, I Had to Learn to Love My Grief

November 17 marks International Survivors of Suicide Loss Day, dedicated to those affected by suicide loss.

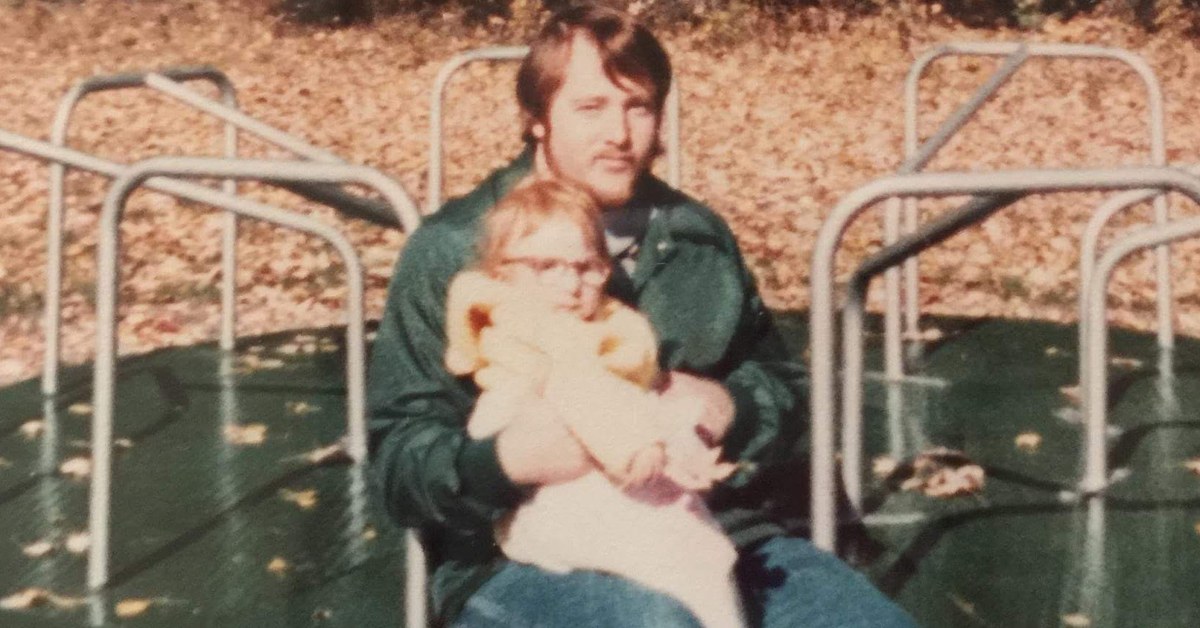

At 21, I thought I knew exactly who I was: Daughter, sister, friend, student, woman with a disability. I was halfway through college and felt like a butterfly excitedly fluttering it its cocoon, just itching to break free and fly. Then, on a regular Monday morning—15 years ago this year—my father died from suicide.

Just like that, my whole life changed. My father’s death was sudden, unexpected, devastating—but above all, it was confusing. For the first time in my life, I felt lost.

Didn’t the universe know this wasn’t supposed to be my life? The suicide of a loved one leaves you in limbo with no way out—full of unfinished business and unsaid words that you’ll never get the chance to say. It’s the ultimate in cruelty—suicide keeps taking things long after the person has died. You’re forever reminded that there should have been more. More birthdays. More family road trips. More memories. More time. More. More. More.

As my family grieved, I felt out of place. Twenty-one is a weird in-between age—I felt on the cusp of adulthood but still wanted the guidance and reassurance of my parents. There were grief books for widows and grief books for children and teenagers, but no one really talked about what it’s like to lose a parent when you’re in your early 20s. Unlike “widow” or “child,” there was really no label that quite described the sense of loss I carried.

No grief book could tell me what it would feel like to see reminders of my father: birthdays, holidays, little girls holding their dad’s hand. Even worse, there was no way to prepare myself for what it would feel like to graduate from college and not pick out my dad’s smiling face from the crowd as I accepted my diploma. When a loved one commits suicide, they’re both everywhere and nowhere.

The most distressing and concerning thing about being left in the aftermath of a loved one’s suicide, I came to realize, is that it decimates your sense of identity. I was no stranger to feeling different—growing up with a physical disability, I was used to feeling different from my peers—but my father’s death brought with it an entirely new sense of isolation. I suddenly felt like a stranger in my own life, isolated from the person I used to be.

A loved one’s suicide doesn’t just leave you mourning for their life, it also leaves you mourning for your own.

That’s the thing no one tells you about dealing with a loved one’s suicide: It doesn’t just leave you mourning for their life, it also leaves you mourning for your own. A part of me died that day too. It took me a long time to realize in the aftermath of suicide, you have to grieve not just for your loved one, but for yourself, too.

I found myself again in subtle ways, little by little. A decade in therapy helped me deal with the effects of my father’s death. Blogging about my journey also helped. But what has made the biggest difference in my well-being is letting myself lean into my grief instead of running from it.

We’ve been conditioned to believe that grief is a bad word and something to be avoided. We even like to tell people how to grieve, when to grieve and, perhaps most importantly, when to stop grieving and just move on. But the more I talked and wrote about my grief, the more I realized that grief isn’t the enemy. Everyone’s grief is different—it’s as unique and individual as the losses we experience—but owning my grief, finally helped me find some relief for all my anxiety and sadness. Grief is not out to get you—it can actually be there to help you.

I like to think my 21-year-old self is still with me, tucked inside my heart, maybe even right next to the spot where my grief resides. I think there’s a place for all three of us—my grief, the girl I used to be, and the woman I am today—to coexist. All three make up the fabric of who I’ve become and in a way, they’re all linked. You can’t really have one without the other two. There’s a certain beauty in that.

When I remember that, I can tell the 21-year-old girl trying to piece together her life in the fallout of suicide that everything is going to be okay. I can spread my wings and my grief and I can finally get the chance to fly.

Melissa Blake is a freelance writer and blogger covering disability rights and women’s issues. She has written for The New York Times, CNN and Glamour, among others.