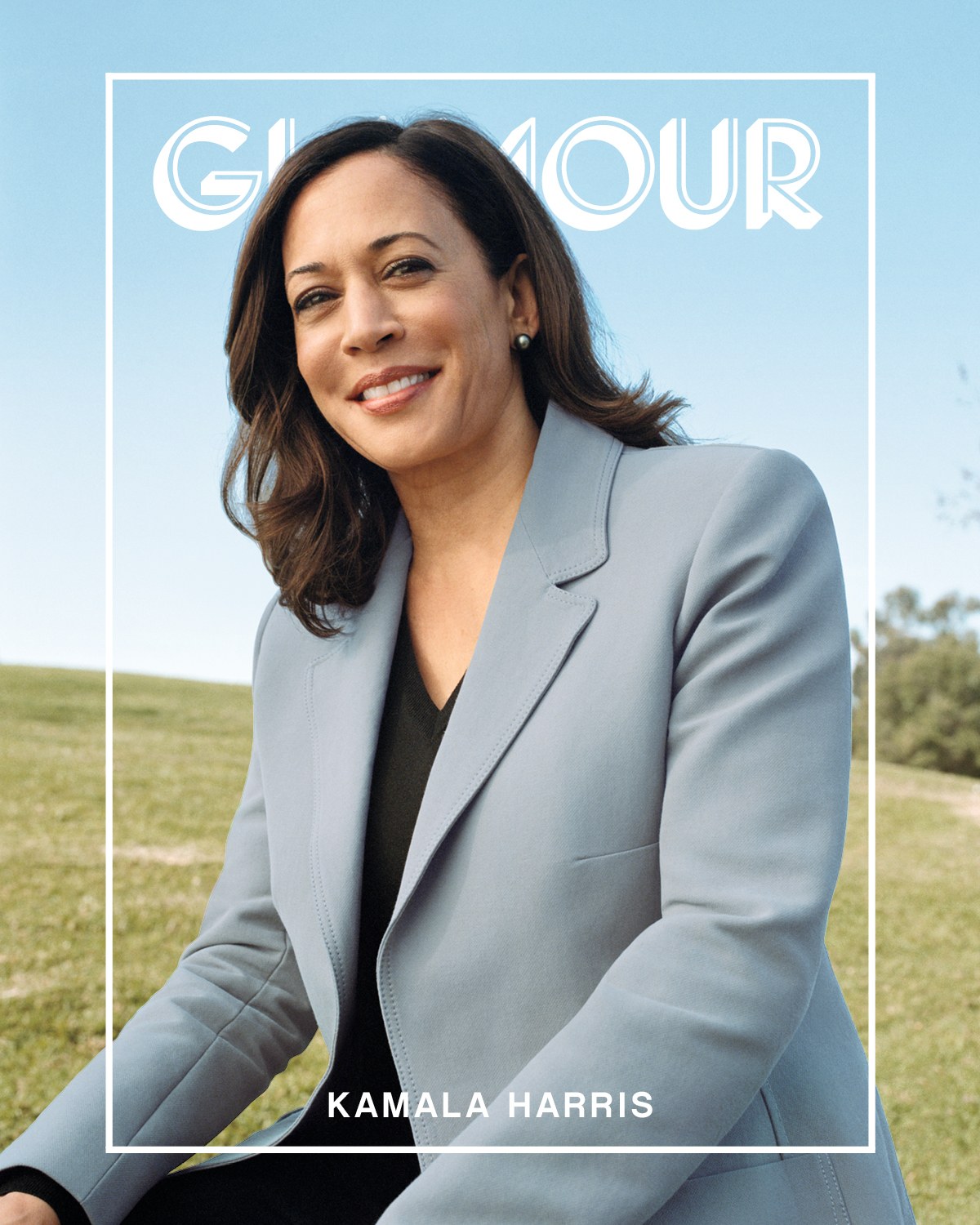

Kamala Harris Is the Politician America Needs Right Now

If you want to ask Senator Kamala Harris whether she’s planning to run for president, keep in mind her favorite Cardi B track: “Be Careful.”

The California Democrat will answer with polite exasperation because to discuss the race with her now, she believes, implies that political ambition motivates her work in the Senate. Instead it’s a deep sense of justice that drives her. “I’m just trying to get at the truth,” says Harris, 54. “I don’t believe my time is to sit here and spew poetry. It’s not for some kind of performance art. It’s not about grand gestures.”

Still, the narrative of her rise is the stuff great political careers are built on. Elected in November 2016, Harris is the lone African American woman in the Senate and its first ever Indian American. She was appointed by Democratic leadership to a seat on the powerful Senate Judiciary Committee and has pushed legislation centered around national security, civil rights, and bail reform (an issue on which she has found common ground with Senator Rand Paul, a Republican from Kentucky).

PHOTO: Zoe Ghertner/Art Partner/Courtesy of Vogue

Outside Washington she’s gained fans and critics for her well-documented blunt talk. She’s been on the front lines of every major issue in 2018, and the viral clips add up: Harris grilling Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen Nielsen about the Trump administration’s controversial child-separation policy; staring down Attorney General Jeff Sessions over his contacts with Russian nationals; pressing then Supreme Court justice nominee Brett Kavanaugh to name laws that govern the bodies of men (as abortion laws govern the bodies of women). After that exchange left Kavanaugh flustered, Trevor Noah, host of The Daily Show, tallied the scorecard: “Goddamn, Kamala Harris brings it.”

Harris credits her childhood as a daughter of immigrants for her confidence—even swagger. Her mother, Shyamala Gopalan Harris, a student from India, and her father, Donald Harris, an economics student from Jamaica, met as activists in the civil rights movement. As children, Kamala and her sister, Maya, followed them to marches. “It was the sixties and seventies, a charged time where everyone in my life was very actively involved,” Harris says. “One of the soundtracks of my childhood is ‘Young, Gifted and Black.’ It was about being told you can do anything you want to do.”

“My mother always told me, ‘You may be the first to do many things,’” she says. “‘Make sure you’re not the last.’”

But Harris absorbed another message too: You’re accountable. After her parents divorced when she was seven, her mother emphasized it. Harris remembers coming home and complaining about some mishap at school. “Other kids’ parents would give them a big hug, ‘Oh, what happened, I’ll handle that,’” she recalls. “My mother would look at me: ‘Well, what did you do?’ ” Harris learned to make her peace with it: “I was like, ‘You never took my side.’ I realized she was teaching us that you’ve got to identify your position of power in a dynamic and not let things just happen to you.” At Howard University, Harris joined the debate team and became a member of Alpha Kappa Alpha, the country’s first African American sorority. Jill B. Louis, who pledged in spring 1986 with Harris, remembers a calm about her even then. “She was always a model of stability and composure,” Louis says. “Night or day, she was never rattled.”

Harris went on to law school at University of California Hastings College of the Law and became a prosecutor, determined to enact criminal justice reform from within. “There is certainly a very important role to be played being on the outside,” she says. “But there is also a role to be played being on the inside at the table where the decisions are being made.” After, she served as district attorney of San Francisco and then was elected attorney general of California. There she worked in the trenches with now Senator Catherine Cortez Masto (D–Nev.). “When you’re the top law enforcement officer of the state, you are going to be surrounded mainly by men,” says Cortez Masto, who was attorney general of Nevada at the time. “Some, but not all men, are going to be dismissive. You don’t let that slow you down. The Kamala Harris that I know is not going to be forestalled by anybody trying to get in the way of her doing her job.”

Sitting on a couch in her Senate office, across from a bust of Thurgood Marshall, the first African American Supreme Court Justice, Harris connects her time as a prosecutor to her responsibilities now. It’s the last week of September, and a vote on Kavanaugh looms. She knew the nation was overdue for a public conversation about sexual assault, she says. When she’d overseen jury selection for such cases as an attorney, men and women would often ask to be excused. Behind closed doors, they’d say, stricken, “I don’t want to share this in the open courtroom because I’ve never told anybody, but I cannot sit on this jury because that happened to me.” Not long ago, after a black-tie event, an acquaintance’s wife sent her a note. “When she was 14, she was raped by an 18-year-old student,” Harris says. The woman had kept it a secret for years, but now she implored: “Please fight for women everywhere whose stories may not have been told.

“Leaders need to do is speak truth, even if it’s an uncomfortable truth. I think it is really important that we are fighting for the best of who we are as a country, and I do believe we are better than this.”

Such stories are her motivation now, despite attacks from all sides. Both conservatives and even some progressives have taken up the hashtag #neverkamala to voice their concern that she’s either too liberal or not progressive enough. The White House Twitter account took aim at her in July, tweeting “@SenKamalaHarris, why are you supporting the animals of MS-13? You must not know what ICE really does,” after Harris called for Immigration and Customs Enforcement to be rebuilt “starting from scratch.” (Harris tweeted back: “As a career prosecutor, I actually went after gangs and transnational criminal organizations. That’s being a leader on public safety. What is not, is ripping babies from their mothers.”)

In the meantime, Harris has raised over $5 million to help elect Democrats in the midterms, proof she’s a bankable leader. Her second book, The Truths We Hold: An American Journey, is set for release in January 2019, well-timed for the unofficial kickoff for the 2020 race. About President Trump, she pulls no punches: He “has decided to, I think, spew hate and division,” she says. She’d like to take a different path. “One of the things that all leaders need to do is speak truth, even if it’s an uncomfortable truth. I think it is really important that we are fighting for the best of who we are as a country, and I do believe we are better than this.”

Yamiche Alcindor is the White House correspondent for PBS NewsHour and a political contributor for NBC News and MSNBC.