Read This Before Asking Why Christine Blasey Ford Waited to Tell Her Brett Kavanaugh Story

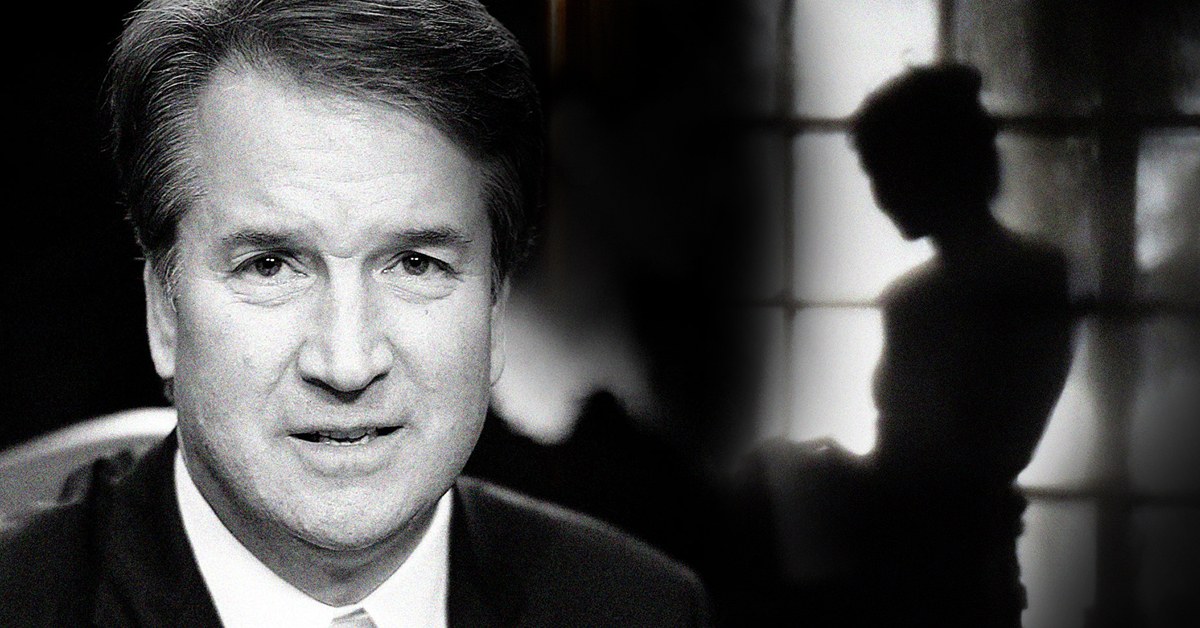

On Monday, the #MeToo movement will get its highest wattage moment yet when psychology professor Christine Blasey Ford and Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh testify in front of Congress about one night in Maryland over 36 years ago.

Ford’s lawyer calls what happened an “attempted rape,” involving Kavanaugh shutting her in a bedroom, pinning her down while pawing at her bathing suit, and clapping a hand over her mouth when she screamed; Kavanaugh says he “categorically and unequivocally” never did anything of this sort to Ford or anyone else.

Monday’s hearing is being touted by lawmakers as a chance to find out the truth. But it’s also going to be, in many ways, a public trial for the woman who accused Kavanaugh. With rape culture and victim shaming working overtime, as it so often does in our society, a familiar question will be on the table: Why did she wait so long to come forward?

Conservatives are already teeing up the argument that jumping on a girl and pawing at her is the type of every day occurrence that shouldn’t make headlines. “Sorry, but having a drunk 17 year old BOY grope you at a teenage party is not newsworthy!” one Twitter user posted this week. And by the standards of 1982, when the alleged incident occurred, they’re right. That adds context when considering Ford’s decision to keep the experience to herself. Back then, the phrase “date rape” was newly minted in the lexicon and not widely used. Boys did whatever they wanted to girls. And girls mostly accepted this as the natural order of the species. “Boys will be boys,” explained a lawyer for three high school football players in Glen Ridge, N.J. who sexually assaulted a mentally disabled 17-year-old girl with a baseball bat and a broom handle in 1993.

Back then, as I chronicled in my book Blurred Lines: Rethinking Sex, Power, and Consent on Campus, Americans didn’t consider anything that wasn’t a violent assault by a stranger to be rape. Even intellectuals in the 1980s and 1990s didn’t take sexual assault all that seriously—they treated it more as a philosophical koan of sex relations than an important social issue. In David Mamet’s Oleanna, a play about a feminist college student who accuses her professor of rape, he calls her “frightened, repressed, confused . . . abandoned young thing of some doubtful sexuality who wants power and revenge.” Controversial academic Camille Paglia, extremely popular in those decades, argued that masculine sexual aggression was normal, and a woman’s only choice was to protect herself; to say otherwise, she declared later, was to join a brigade of “fanatical sex phobes.”

In our era of #MeToo reckoning, these voices have become quieter and things have finally started to change. But things haven’t changed enough for one woman’s word to be believed simply on its own without corroborating evidence. Or without the argument that her experience has timed-out—that statue of limitations exist when it comes to trauma.

If history is any indication (or Justice Clarence Thomas’ defense when accused of sexual harassment during his Supreme Court confirmation hearings in 1991) Kavanaugh is going to use the usual playbook to defend himself: calling himself a standup fellow—or, as Kellyanne Conway said, “a man of character and integrity”—and explaining he’s shocked, simply shocked, by this character assassination. He’ll talk about being raised right by his parents and point out that he’s a “carpool dad” for his two daughters, hoping that their mere existence will act as a shield against accusations against a member of their sex. But most importantly, he’ll talk about whether Ford told anyone at the time what happened that night.

No one who understands the nature of trauma and sexual assault thinks that it’s a big deal when women don’t tell an authority for months or years about an assault. Not every woman wants to upend her life in the pursuit of justice, or even deal with criticism about “playing the victim” from their peers or institutions. Couple that with an era where women, if something bad happened with a guy, would likely keep it to themselves due to the blasé attitude surrounding sexual violence and the permission boys and men had to engage in it. A cool Gen-X girl brushed off anything untoward, knowing there was no percentage in calling a boy out because even if a few of her friends believed her, the rest of the school would not. And how could they? In the 1980s, there were no tools and very little language to identify or corroborate assault.

As a friend who went to high school in the 1980s posted on Facebook this week, what might have happened to Ford “happened all the time when I was growing up and no doubt still does.”

“This is such a common story,” she wrote. “This happened ALL THE TIME. What also happened all the time was that women who this happened to didn’t really talk about it much because, see above.” Whether Kavanaugh is confirmed to the Supreme Court or sent off to play endless rounds of golf, one thing we know is that women aren’t being quiet about this any longer. But in addressing sexual misconduct, we must also grapple with our past and understand that the experiences of women of a certain age group cannot be examined without historical context. We cannot dismiss claims with the lazy excuse that “that’s how it was then.”

In fact, in cases like Ford’s, there’s no excuse to resort to old victim-shaming tropes. We have the tools, now. We must use them.

Vanessa Grigoriadis is the author of Blurred Lines: Rethinking Sex, Power, and Consent on Campus, out October 2018, and a contributing writer at The New York Times magazine and Vanity Fair.