Look Away, Look Away

“I wish I was in the land of cotton, old times there are not forgotten,

Look away, look away, look away, Dixie Land.

In Dixie Land where I was born in, early on a frosty mornin’,

Look away, look away, look away, Dixie Land.”

– Chorus from Dixie

“And I want to thank, on behalf of Black America, white America. Thank you white America for making us tough. Because we’ll get through this terrorist stuff. White folks made us tough because they’ve been terrorizing us for 500 years. […] We’re used to terrorists. This is no big deal for us. I’m worried about my white friends. They ain’t gonna make it through this. I’m opening up a school: How To Be A Nigga in America and Survive.”

– Paul Mooney (1941-2021), from a standup performance just after 9/11/2001

When I was at UCLA Film School, the venerable Professor (now Professor Emeritus) Howard Suber had a legendary class on story that I would later realize took structuralism and made it accessible and intriguing. His class promised to take even the most film savvy student on a ride by revealing things about the medium that were obvious upon being pointed out but had been obfuscated by shallow received ideas about storytelling.

One of the moments that forever changed how I thought about storytelling was when Professor Suber asked us a simple question: what is the chief characteristic of a hero? Of course, the answers came quickly: courage, intelligence, honesty, compassion. Suber listened with an impish smile that let us know none of these were correct. And then he gave his answer: the chief characteristic of the hero is the ability to withstand pain; specifically pain that the rest of us worked hard to avoid.

The words fell like feathers in the quiet but the impact made a tremor travel through the room. We all immediately recognized this as truth but Suber dutifully pointed out examples. Rocky Balboa (particularly the Rocky of the original film) is the only example he gave that I can still remember. When I relay this lesson to my own students today I typically point to moments like the climax of “The Avengers,” when Tony Stark finally achieves his apotheosis by carrying a nuclear missile into space. The act almost kills him and also marks him for the rest of the series.

To be clear, there are many types of pain, and any will do for the hero of a story. Physical pain is not the only kind of pain Professor Suber was referring to. It is a (slightly dubious) cliché of screenwriting pedagogy that stories are about conflict, but I left Professor Suber’s class feeling that the greater truth was that in drama, characters are born to suffer for us.

This idea has come back to me many times in the last year as I witnessed and took part in the Great Black Pain Discourse. For the social media uninitiated, I will explain. There is a growing sentiment spreading across the timelines of Twitter and the comment sections of Facebook, particularly in the wake of projects like “Them” and “The Underground Railroad,” which holds that too many of the stories about Black people are overly focused on suffering and trauma. The argument holds that such films no longer serve a healthy purpose. Some even go so far as to question why Black suffering holds such allure, suggesting that there’s a pornographic appetite for Black suffering that filmmakers are unwittingly feeding.

This renunciation of Black Pain doesn’t square with what I know about why we watch films. What about catharsis, the notion that explorations of pain and suffering offer a necessary emotional release? Catharsis is an old concept. Is it possible that the modern world has exceeded the cathartic capacity of dramatic storytelling? This is a complicated question with no easy answers in sight. But perhaps by going back in time and moving through the history of film can we get a better perspective.

At the outset I want to address the “let people watch what they want” point that often comes up around this subject. It has been said that this is a pointless debate because the individual viewer reserves the right to watch what they want and shun what discomforts them. To this, I say, of course. We all pick the films that speak to us on an individual level. If stories of enslavement don’t speak to you, if you feel you know all you need to about this shameful foundation of American life, I cannot argue with you. But the filmmaker in me has to ask what becomes of Black Cinema if we turn away from difficult stories? Will Black Cinema grow if we only depict joy and happiness? Or will it devolve into mere entertainment, an escape from life’s hard truths rather than a weapon to do battle with them? The chilling answer might lie in the recent NAACP Image Awards, where “Bad Boys For Life” beat “Da 5 Bloods,” “One Night in Miami,” “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” and “Jingle Jangle: A Christmas Journey” for Outstanding Motion Picture.

It is at this point fairly common knowledge that American cinema has a racial original sin just as the nation itself does. D.W. Griffith’s landmark 1915 epic “The Birth of a Nation” was a formal leap forward for the medium. It unambiguously told the story of Reconstruction as a tragedy and cast white supremacist terrorism as heroic. It was the first American blockbuster, and it succeeded in bringing the largely dormant Ku Klux Klan into the 20th century. Griffith’s disgraceful and mendacious racist epic did irreparable damage to the moral fabric of this country and more than that he set a terrible precedent: he shows that history, whether willfully misrepresented or misunderstood, can be a powerful chisel to sculpt the future. We Americans are a forward looking people, even if our tendency to disregard the past means we are tripping over its tendrils as we dash ahead.

One of the more striking arguments against depicting slavery is the notion that it has been done to death. To listen to this argument, you would assume slavery films were a time-honored American genre like Westerns or Biblical pictures. But the reality is slavery is touched on fairly rarely in American film. However, the subject is so sensitive we have a perception that there are far more films made on the subject than there actually are. While it is difficult to come up with an exact number or percentage of American films about slavery, a Wikipedia entry on slavery films lists just 110 titles, many of which are not American films and/or are not about American slavery. So while this is far from scientific exactitude it tends to suggest under 100 films made that touch on slavery in a medium with over a century of history (and most of those films skew newer, meaning they were mostly made after 1970). The misperception about slavery films is understandable. Both “The Birth of a Nation” and “Gone with the Wind” (1939) have such an outsized place in American (film) history they suggest a genre that doesn’t truly exist. But the truth is white supremacy more usually expressed itself in Golden Age Hollywood by erasure. They simply relegated non-whites to the periphery, to the edges of the screen or off the screen altogether.

For organizations like the NAACP, these two pillars of American film gave them two related objectives: combatting romanticized depictions of slavery and its aftermath and also a push for greater representation on screen. The fight over Disney’s “Song of the South” (the 1946 film is set during Reconstruction and Uncle Remus is the sentimentalized former slave who wants to remind us that things back then maybe, just maybe, were better than they are since the North meddled) was bitter and the voices raised back then in objection to the film were stentorian. As detailed in a recent season of Karina Longworth’s outstanding You Must Remember This podcast, the controversy put a permanent mark on the film: it is not available for streaming on Disney+ (even though the film enjoyed many re-releases, including a lucrative run during the Reagan Era).

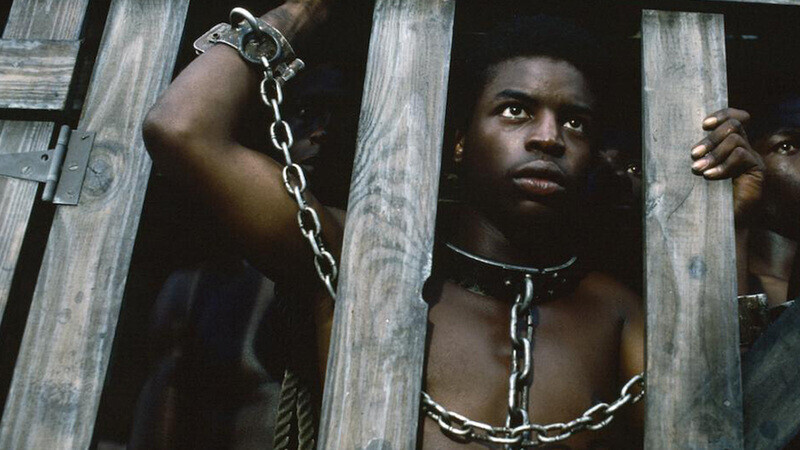

After the tumult of the 1960s, the 1970s was the era when the goal of representation which Black organizations had fought for began to bear fruit. There were more films about Black people (which also led to more films featuring non-Black people of color), more opportunities for Black actors to appear in supporting parts, and all of this culminated in 1977 with the debut of “Roots,” an ambitious television miniseries that traced the journey of writer Alex Haley’s ancestors from Africa into American bondage. “Roots” changed America’s perception of slavery overnight in a way that the American educational system had, by design, failed to do.

This August marks Alex Haley’s centennial birthday. In the 1970s, he had already been put on the map by collaborating with Malcolm X on his autobiography and the way in which he labored for years to unearth his family tree from the fog of chattel slavery has become the stuff of legend. By the time the miniseries came out, “Roots” had become a cultural phenomenon. According to an article in the New York Times (dated February 2, 1977), historian Roger Wilkins wrote that “Roots” “may have been the most significant civil rights event since the Selma to Montgomery march of 1965.” It was a ratings smash, a moment the likes of which only come around once in a generation. The miniseries had its critics: “Very frankly, I thought the bias of all the good people being one color and all the bad people being another was rather destructive.” These were the words of Ronald Reagan, who was just three years away from being elected president.

Regardless of whether or not it should be so, movies and television play a profound role in how history is understood, processed, and allowed to influence our contemporary dialogue about race. So if we begin to turn our backs on films and TV that grapple with heavy themes and daunting subjects, what could be the long range impact of that choice? Have we arrived at the point where we know all we need to know about the roots of American white supremacy?

As the 1980s continued, we saw more representations of the Jim Crow era and fewer attempts to grapple with the subject “Roots” had taken on. The rise of Reaganism in the 1980s led to contrapuntal measures in race films, the most famous of them was the White Savior trope. As if to address Reagan’s critique of “Roots,” more and more films about the oppression of Black people were centering white people and following their transformation from passive participant in an unjust system to active opponent (I haven’t read Roots but from what I understand several parts for white people were beefed up during the adaptation process to allay network executives’ fears that the miniseries relied too much on the point of view of Black people). This effectively made Black people the objects rather than the subjects of stories about their lives and hardships. Only the white characters were granted inner lives. The Black people were meant to suffer and through that suffering ennoble the righteous white person who had the courage to reject the white supremacy they’d been taught.

As if guided by the Newtonian laws of physics, the White Savior film was disrupted by an explosion of Black Cinema in the late 1980s. A new wave of African-American filmmakers had arrived, and they were intent on telling Black stories for Black people while simultaneously demanding space in the mainstream. The stories they chose to tell were overwhelmingly contemporary, of the moment, but with a deep understanding that today is built on yesterday and whatever joys one experiences today are linked to the past which includes dried tears and memories that scar.

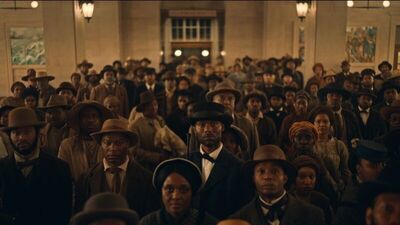

This Black Cinema boom of the late ’80s and early ’90s ebbed in the (George W.) Bush era. But such waves are cyclical, and with the Obama era came the first film directed by a person of African descent to win the holy of holies, the coveted Academy Award for Best Picture. It was directed by a British filmmaker (of Grenadian and Trinidadian descent) who had an outsider’s audacity in telling the story of a Black American pressed into slavery as a freedman. And in retrospect, it all made sense. Steve McQueen did not have the baggage of someone like Spike Lee (who had been dismissed by many as a self-aggrandizing loudmouth and bomb thrower) in the minds of the largely white Academy voters. “12 Years A Slave” fit a provocative pattern for McQueen whose debut feature film “Hunger” was the first film about “The Troubles” to be made in several years and some critics questioned his take on the 1981 hunger strike of IRA prisoners.

Like most artists, McQueen was inexorably drawn to the taboo. He dared to revisit The Troubles, he earned a dreaded NC-17 rating for his sophomore effort (“Shame”) making a film about sex addiction just as sex was being ushered off American theatrical screens altogether, and now he was making a film about the subject most of us in this country would rather not deal with or think about.

McQueen’s 2013 film was a box office and critical success and it led to a renewed interest in exploring this tragic history. Perhaps the film’s success had the unforeseen consequence of emboldening the stance that we had finally seen enough of slavery. It was around this time that I began to see this position be spoken in public and on social media. For an African American of my generation, this took me aback. I was brought up with the ethos that as ugly as aspects of our history were, we had a duty to face it. Like many of my generation I watched all six episodes of “Eyes on the Prize” (first volume) and made sure my own son saw it as well. But something was changing. And this ethos was being displaced by something else. People were no longer even paying lip service to bearing witness to history, now they were flat out saying “no more.” What changed?

Just months after “12 Years A Slave” made Oscar history (the ceremony took place on March 2, 2014), we began to see the killings. Less than six months after that film won the big prize, Eric Garner’s murder (July 17, 2014) in Staten Island was recorded and went viral. Michael Brown was murdered one month later in Ferguson, Missouri. No tape of that murder, but Ferguson became the national nexus for the fight against police acting with impunity and treating Black lives as cheap and expendable.

In short, McQueen’s beautifully crafted but emotionally excoriating triumph coincided with a wave of images of Black Death. These images are nearly inescapable: they visit us as we have a drink or a quick bite through televised news, they snake across our social media timelines, and they play in our minds whether we want them too or not. And once this wave begins, it doesn’t really stop. Philando Castile’s murder (July 6, 2016) was even live streamed on Facebook by his girlfriend.

These videos have taken a psychic toll. And many have begun to wonder if perhaps the perpetual “toughening up” that Black people have experienced in America may be more deleterious than we want to admit. Perhaps that which doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. And perhaps that which doesn’t kill you depletes you before the next inevitable assault.

These videos are horrific, but it is indisputable that they have been a major factor in forcing this country to have a conversation about law enforcement and race that is long overdue. I find it hard to believe the conviction of Derek Chauvin for the killing of George Floyd (May 25, 2020) would have happened without this terrible montage to which we have been forced to bear witness. It is incredibly upsetting for many to accept this. Words should be enough. But they are not. Images have a power all their own. That’s why in 1955 a grieving mother named Mamie Till insisted on an open casket funeral to show what the world had done to her beautiful son. This simple but painful act helped galvanize change in America.

So taking into account this hideous stream of Black Death, it is understandable that some have now found representations of Black Suffering too triggering. I am sure “Roots” would have had a different reception if television and the Internet were bringing Black Death to our homes on a weekly and daily basis.

This taps into an old debate about cinematic representations of atrocity. Jean-Luc Godard famously cited his failure to stop Steven Spielberg from making “Schindler’s List” as one of the reasons why he didn’t deserve the Academy’s 2010 Honorary Award. In the 1980s, Godard began to use real video clips of violence and its aftermath in his landmark Histoire(s) du cinéma essay film (as well as images of pornography as if to underscore the connection between sex and death in cinema). Godard is supremely suspicious of filmmakers who want to reconstruct atrocity and infers (in the case of American filmmakers especially) a totalitarian impulse behind such stories; he believes that recreated atrocity asks the audience to feel without thinking, and for Godard, that way lies fascism.

Godard has never applied this reasoning to depictions of American slavery and racist violence, but I think his reasoning echoes and finds common cause with some of those who object to current depictions of slavery. “Who is this film for, and what purpose does it serve?” are the questions that hang over any film that wades into such territory. And the 2020s have thrown one more element into the combustible mix: genre.

There are countless examples of genre (specifically horror and science-fiction) being used to explore questions of race and history from the last two years alone, but clearly the breakthrough here was Jordan Peele’s Academy Award-winning “Get Out,” which borrowed the horror formula of Ira Levin to make a visceral experience rooted in free-floating racial anxiety and the perceptive take that the progress represented by Obama’s presidency might in fact mask something sinister with deep roots in American soil.

As I write this we mark the centennial of the Tulsa Race Massacre, one of many white supremacist ethnic cleansings that resulted in the death and the destruction of a vibrant African-American community. The perpetrators faced no consequences and the incident was largely withheld from historical account unless you sought the information out on your own. Damon Lindelof’s laudable choice to open his miniseries sequel to Alan Moore’s “Watchmen” changed that, possibly for good. The fictionalization of this massacre did more to educate the public about it than all the books and documentaries that came before it. And I think that fact issues a stern warning to those who would seek to have Black Trauma eliminated from the screen. To erase such history from film and television risks erasing it from the public consciousness altogether which only serves the aims of white supremacy.

At this moment, Republicans across the country are trying to criminalize any attempt to educate students about this terrible history (it’s a fait accompli in the textbooks, but they know teachers have been making up for these elisions via instruction). And without films and television offering a different perspective from their lies, their warped view of the past might become even more widely accepted than it already has. In the vacuum we will inevitably get films that much like the song “Dixie” (which was written to say that slavery as an institution was worth defending) attempt to spin history in a way that brutal depictions of slavery do not.

Assuming that we agree that this history has a place on our screens, the very fair question remains how it could and should be handled. Two recent examples come to my mind. Jayro Bustamante’s “La Llorona” caused quite an uproar in his homeland of Guatemala when word spread that his new film was a thinly veiled horror reimagining of the trial of former dictator Efraín Ríos Montt for genocide against the indigenous people of Guatemala. This led to a tense production and growing discomfort with the airing of “dirty laundry” which only abated when the film received positive reviews from American and European critics. We’ve begun to see more and more of this here, employing the horror genre as a way of overcoming the audience’s discomfort with confronting death and brutality. It should be noted that in the context of Bustamante’s film, it is the oppressors who are the targets of the haunting. We watch the ex-dictator and his family pay for his sins and when we do see the genocide, one of the dictator’s loved ones is forced to experience it the way the Mayans did. The supernatural is employed in this film to correct an evil, not to amplify it.

I was also struck by another more realist handling of atrocity: Jasmila Žbanić’s Academy Award-nominated “Quo Vadis, Aida?,” which depicts the struggles of a Bosnian U.N. translator to save the lives of her sons and husband from the 1995 Srebrenica Massacre during the Bosnian War. Comparing this film’s telling of attempted genocide to earlier decades’ treatment is revealing. We have moved away from the need to see atrocity on screen as seen in Spielberg’s “Schindler’s List.” The Bosnian film represents the next chapter in this kind of storytelling by giving us clear indicators of the stakes and placing the rape and mass murder just off-screen. This new restraint does nothing to blunt the devastation of the characters in the end. Žbanić’s film offers a new approach to difficult subjects. The shocking imagery is gone, but the pain is not.

But above all, I fear that none of this matters. I worry that the audience for difficult films about Black history is dwindling, and that regardless of the way Black Death is handled or how explicit the violence is, the audience has begun to withdraw. I am of course well aware that Black Cinema cannot only depict the suffering and the pain. Steve McQueen’s brilliant “Small Axe” films addressed that by making sure Black Joy was as much a component as Black Suffering. McQueen understands that our joy and our agony are two sides of the same coin, a coin that is flipped on us without warning. Black Joy is irrepressible (who else would turn the act of standing in punitively long lines to vote in Georgia into acts of celebration as seen in viral videos last election cycle?). We will always make our comedies, sing our love songs, and envision our own kind of heroism. Yet if we spend a season focusing exclusively on Black Joy, and eradicate the sorrow and heartbreak, we are only telling half of our story.

Our joy and our pain are inextricably linked because our joy, our Black Joy, has always been an act of defiance. And that joy loses its profundity and power on its own. We may think we want to see stories where people that look like us just win and thrive and embody fabulousness, but Professor Suber’s words echo in my ears and I suspect in time we’d come back to the simple truth that the hero’s journey is one of pain. If this urge to shun that pain and catharsis grows and Black Cinema abdicates its responsibility to use cinematic craft to elevate the total breadth of our history, then the films by Black filmmakers will at best function as disposable entertainment and lose the range that elevates a story to art. One of our greatest African-American directors, Barry Jenkins, has just given us a towering adaptation of “The Underground Railroad,” a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel. It remains to be seen whether or not this work will suffer because of reluctant Black viewers. Cinematic golden ages never occur solely because of filmmakers. They also require critics who can help the audience understand challenging work and an audience willing to take the ride. If any one of these is absent from the equation, the golden age that might be is lost.