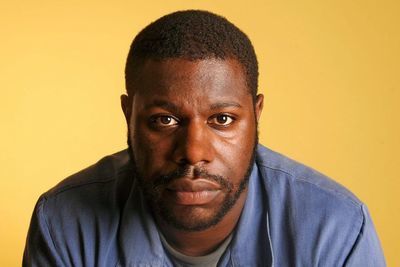

Steve McQueen Honored at Chicago International Film Festival

The Chicago International Film Festival commemorated the 20th anniversary of its Black Perspectives program by honoring a man who, after directing three features, has proven himself to be one of our greatest living filmmakers. Steve McQueen, the first black director to win a Best Picture Oscar (for 2013’s astonishing “12 Years a Slave”), spoke about his career in a fascinating conversation moderated by University of Chicago professor Jacqueline Stewart on October 22nd. Stewart did an excellent job of illuminating the recurring themes that link the English auteur’s work in provocative ways, such as “structural inequality, abuse of power and the marginalized.”

Prior to making feature films, McQueen created artworks in a variety of different mediums, from paintings and moving images to the staggering “Queen and Country” that featured a series of postage stamps displaying portraits of British soldiers who died during the Iraq War. This was one of many pieces on display at a 2012 exhibition of McQueen’s work at the Art Institute of Chicago, which kicked off nearly four years prior to last Saturday’s CIFF presentation.

What led McQueen to take on his first major film project was the life of Irish Republican hunger striker Bobby Sands. It was a story he believed demanded to be told as a feature. He considered Sands’ self-declared strike and subsequent death to be among the most important events in British history, and was amazed at how few people knew about it. Portraying the horrendous living conditions and unforgiving brutality faced by the prisoners was a task most first-time filmmakers would balk at, but McQueen has always desired “the burden” of bringing difficult stories to light, especially ones that exist on the margins. The Irish cast members were paralyzed by “the Troubles” in their youth, and this film gave them an opportunity to work through that volatile period in their country.

The resulting picture, 2008’s “Hunger,” is one of the most impressive debut features ever crafted. McQueen had never been on a film set and refused to visit any before production began because, as he told Stewart, “I wanted to do it my way.” The first clip he screened for the audience was a galvanizing sequence in which prisoners are stripped and beaten by guards in what appears to be standard protocol. McQueen was stunned to observe the violence he had instigated as a filmmaker, and his body developed a rash once filming wrapped, likely as a result of delving into such punishing material.

Earlier on the red carpet, McQueen spoke of his goal to have “the movie screen become a mirror that reflects the audience in the theater” as well as “a truth they may not want to see.” That is certainly true of sex addiction, which the director explored in his powerful second feature, 2011’s “Shame,” which re-teamed him with the tirelessly committed actor Michael Fassbender. When Stewart asked him about the film’s full-frontal nudity, McQueen quipped, “I have a penis. Who hasn’t seen one?” Nudity has been an essential element in the director’s work going back to his first work of film art, 1993’s “Bear,” which shows two naked men (one of them McQueen) who regard one another with a mixture of aggression and eroticism similar to that of the young men in several coming-of-age films at CIFF, such as Barry Jenkins’ “Moonlight” and André Téchiné’s “Being 17.”

The clip McQueen chose to show from “Shame” was a shot of Fassbender jogging down a street in NYC as his sister has sex with a repugnant man in his apartment. The director told Stewart that this sequence provided the audience with “a breath, a lull, that allowed them to digest the previous scenes,” much like the “avalanche of words” that follows the first hour of near-wordless violence in “Hunger.” McQueen’s cinematographer on all three pictures, Sean Bobbitt, shot Sands and the priest in silhouette during their extended conversation, thus inviting the audience to lean in and focus on their words, while the camera remained stagnant. It is the director’s love of experimentation that makes his work so rich, and also what caused him to leave NYU. “I wanted to throw a camera up in the air, but they wouldn’t let me,” explained McQueen.

Just as Sands’ story was egregiously underreported, “Twelve Years a Slave,” the 1853 memoir of abolitionist Solomon Northup, was virtually unknown outside of academic circles. Northup’s book chronicled his experience of getting kidnapped and sold into slavery, an achingly personal work of literature that, to McQueen, is the African equivalent of Anne Frank’s diary. McQueen’s adaptation of the book was such a critical and financial success (earning an estimated $187 million at the worldwide box office) that it opened the door for other films about that period in history to be made. The director can’t understand the notion of “slavery movie fatigue,” in part because so few have reached the screen, and in part because the narratives themselves are so compelling.

Time and again, McQueen’s film exposes audiences to people and situations unlike any previously found in a historical drama. A key example would be the character of Mistress Shaw (Alfre Woodard), the black wife of a white plantation owner, who is referred to in one line of Northup’s book, and was expanded by McQueen and screenwriter John Ridley into a fully realized being. The final clip McQueen selected was Woodard’s scene opposite Patsey (Oscar-winner Lupita Nyong’o) and Solomon (Chiwetel Ejiofor, whose “nobility” the director likened to Poitier and Belafonte). On the red carpet, I asked the director about one of the film’s most visceral moments, when Solomon is hung from a tree just enough for his toes to balance on the ground. As the camera held on Solomon for what felt like an eternity, I held my breath until my throat started to feel as if it was constricted. You don’t just watch a scene like that, you feel it.

“I wanted to create a situation that would allow for a multitude of narratives in one shot,” said McQueen. “It was an economy of time. Within that shot, you have Solomon struggling, of course, but then you have the other people on the plantation going back to normal. You see how people had to get used to seeing this ritual torture and somehow had to live with it. Within that one frame, I wanted to show this bizarre situation in which people are going about their daily business while someone is struggling for their life. It can be so much more powerful when there are two or three narratives going on at the same time within one vista.”