I’m a Sound Man: Brian De Palma’s Blow Out at 40

When Brian De Palma’s conspiracy thriller “Blow Out” arrived in theaters in the summer of 1981, the results were pretty much disastrous across the board. Although the film did receive some rave reviews from people like Roger Ebert and longtime De Palma supporter Pauline Kael, most critics dismissed it as just another tawdry exercise from the filmmaker and accused him of once again constructing a movie out of elements ripped off from other films, particularly Michelangelo Antonioni’s groundbreaking “Blow-Up” (1966) and Francis Ford Coppola’s revered “The Conversation” (1974). Commercially, it proved to be equally disastrous. Granted, releasing a serious-minded adult-oriented film at the height of the summer season—a time when audiences were then flocking to the likes of “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” “Superman II” and “Stripes”—was not the wisest move. But the combination of bad reviews and disastrous word-of-mouth regarding its downbeat story and grimmer-than-grim ending pretty much sealed its fate, opening #8 at the box office on a weekend that would be won by another debuting film that would more than double its grosses—the immortal Bo Derek classic “Tarzan, The Ape Man.”

And yet, while the film quickly disappeared from the charts, it did not vanish from the memories of those who did see it. In the years since its release, a reappraisal of “Blow Out” would begin to take hold, thanks in no small part to Quentin Tarantino, who would not only name it as one of his all-time favorite movies but cite John Travolta’s performance in it as one of the key reasons behind his decision to cast the actor in “Pulp Fiction” (1994). Between that, fading memories regarding the initial critical reaction, and the veneration that it received in the popular documentary “De Palma” (2016), the film’s reputation would greatly improve over time to the point where it is now generally regarded as arguably the controversial director’s greatest cinematic achievement. As someone who considers Brian De Palma to be his favorite filmmaker, I not only concur with this assessment towards a film that I have loved and admired since I first saw it nearly 40 years ago, I would go so far as to proclaim it both one of the finest American films of its era and one of my all-time favorites to boot.

Considering how the whole “Blow Out” saga would eventually turn out, it’s ironic to note that it began with De Palma at a high point in a career of many ups and downs. In 1980, he released “Dressed to Kill,” a highly controversial erotic thriller that proved to be a critical and commercial hit during a summer movie season in which many of the more highly anticipated offerings (such as “The Shining”) were being rejected. As a result, he was in a position where he could pretty much pick and choose what he wanted to do next. Although he considered other projects, including one inspired by the murders of labor leader Joseph Yablonski and his wife and daughter and, reportedly, “Flashdance,” he eventually settled on a script of his own, then titled “Personal Effects.” The project would move him away from the grisly thrillers he had become known for with films like “Carrie” (1976), “The Fury” (1978) and “Dressed to Kill,” with a story that would be a more serious-minded and adult-oriented and not nearly as gory. Renamed “Blow Out,” the script attracted the attention of Travolta, whose luster had dimmed slightly in the wake of the failure of the bizarre romantic melodrama “Moment by Moment” (1978) and the tepid response to “Urban Cowboy,” but who was still considered bankable at that point. With Travolta on board, De Palma was able to secure an $18 million dollar budget and the film was a go.

The opening scene is set at a girl’s college dormitory, late one night. Via an elaborate and extended Steadicam shot, we prowl around outside peering in the windows as the unwary residents get into all kinds of barely dressed mischief. A campus security guard begins peeping in on the fun as well, but it is then that we realize that we have assumed the perspective of a knife-wielding maniac who makes short and bloody work of him. The killer sneaks inside the building, manages to get around unnoticed until he gets to the showers (thankfully there is a sign reading “Shower” on the door) and attacks the girl inside, who responds with the weakest and silliest-sounding scream imaginable. We then discover that we’ve just seen the rushes for “Coed Frenzy,” a cheapo mad slasher movie similar to those clogging up multiplexes at the time this was being made. Echoing his fake-out opening from “Sisters” (1973), this brilliant sequence displays De Palma’s sardonic wit and scorn at the kind of gory trash that was all the rage, and which “Dressed to Kill” had been unfairly lumped in with in some quarters, as well as his unmatched skill as a visual stylist (with the singular exception of “Halloween,” none of the slashers from that era looked nearly as good as what we see). While some might argue that the sequence is little more than a gratuitous joke, it’s a clever setup for the story to follow while subtly underscoring one of its recurring themes—that we cannot always believe what we see even as it unfolds before our eyes.

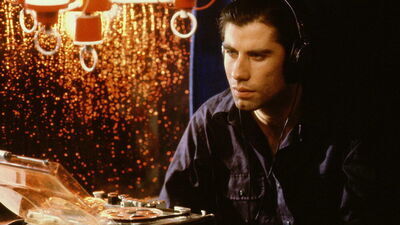

Travolta plays Jack Terri, a sound man working for the Philadelphia-based low-budget outfit producing “Coed Frenzy,” and the film’s producer insists that he go out and record both a more convincing scream and new wind effects in order to replace his tired library sounds. That night he goes out with his equipment to record some ambient sounds and happens to see a car plunging off a bridge, into the water below with a man and woman inside. Jack jumps in and is able to rescue the woman but cannot save the man. At the hospital, Jack is buttonholed by a couple of men who inform him that the dead man was the governor of Pennsylvania—widely considered to be the front-runner for the next presidential election—and that the woman, Sally (Nancy Allen), was not his wife. Jack agrees to say nothing about what he knows about the accident in order to spare the governor’s family any embarrassment, and even helps them to sneak Sally out of the building and away from the press.

Going over his audio recording of the accident, Jack becomes convinced that he can hear a strange noise just before the sound of the tire blow out that preceded the crash. After listening to the tape enough, he becomes convinced that the strange noise was that of a gunshot, which would make the “accident” into something far more sinister. Using his instincts gleaned from a previous career working with the police wiring people up in order to collect information—a job that ended tragically as the result of a poorly timed technical failure that he still feels guilt over—Jack begins to look into the case himself with the help of Sally, who is perhaps not 100% innocent but certainly did not know the magnitude of what she was getting into when she got into that car. Without going into much more detail, I will merely mention that Jack’s investigation raises the interest of two other individuals who turn out to be connected—Manny Karp (Dennis Franz), who managed to photograph the entire accident but whose presence on the bridge that night was not exactly coincidental, and Burke (John Lithgow), a borderline psychotic political operative who knows exactly what happened on that bridge, and who is willing to go to elaborate and even murderous lengths to keep those details from being revealed.

In many respects, “Blow Out” is a recapitulation of the various obsessions that had been driving De Palma throughout his entire career. The murder of the governor is obviously meant to evoke memories of the JFK assassination (with a hint of Chappaquiddick thrown into the mix) and Jack’s dogged attempts to expose the vast conspiracy surrounding it to a public that may not ultimately care is reminiscent of Gerrit Graham’s attempts to crack the Kennedy conspiracy in De Palma’s audacious social satire “Greetings” (1968). Beyond that specific plot concept, the film touches on such elements as voyeurism; a cynical take towards contemporary entertainment; modern technology and the dangers that can come from putting one’s faith entirely behind it; and deeply flawed heroes who are struggling to find some kind of redemption and either fail at it or succeed, only to discover that the price to achieve it may ultimately not be worth it.

Part of De Palma’s genius comes from presenting his narratives in such stylish and striking visual terms that it isn’t until later on that you realize not everything adds up. While the aforementioned “Blow-Up” and “The Conversation” are undeniable inspirations for the film—all three involve emotionally isolated men with a particular skill set that they attempt to utilize when they stumble upon murder plots—De Palma uses such a conceit in “Blow Out” only as a mere leaping-off point for his own unique take on the premise. The resulting screenplay is a bit of a miracle, as it offers a narrative as dense and complex as any that he had done up to that point (or since then), but in a surprisingly graceful and straightforward manner. With “Blow Out,” De Palma allows viewers to grasp what’s going on without letting them get lost in the labyrinth (except when that’s the point, of course) and without any extraneous bits of business. Even the stuff that appears to be extraneous, such as the “Coed Frenzy” opening or a spree of murders of prostitutes, all ends up fitting together in the big picture that De Palma presents with jigsaw precision.

Like practically all of De Palma’s key films, there are a number of elaborately constructed set pieces in “Blow Out” that bring his considerable skills as a visual stylist to the forefront. But unlike some of his other films, such sequences are so perfectly integrated into the storyline they never feel like he’s showing off. Obviously, the “Coed Frenzy” opening is a standout that illustrates that while he’s perfectly capable of cranking out mindless exercise in violent style—the kind that he has often been accused of making throughout his career—he’s no longer interested in such a lack of artistic challenge. There’s also the haunting flashback sequence in which Jack recounts his days with the police and the case where everything went wrong, which serves both as a compelling way to fill in his backstory and explain his cold, cynical attitude towards everything, and to allow De Palma to show what he might have made of “Prince of the City,” a project he was scheduled to do even before “Dressed to Kill” but which he lost out on when the producers elected not to wait a year for Robert De Niro’s schedule to clear up and instead gave it to Sidney Lumet. (This sequence, originally devised for De Palma’s version, will make you look at De Palma’s “Prince of the City” as one of the great unmade movies.)

The climactic chase, in which Jack speeds through the crowded streets of Philadelphia (at one point barreling through the middle of a parade) to rescue Sally fro mthe deadly trap that he has inadvertently placed her in, is such a miracle of filmmaking—both in terms of sheer technique and the emotions that it engenders—that Hitchcock himself would have doubtlessly bowed to it out of sheer admiration. (The scene is especially impressive when you realize that De Palma was forced to reshoot it at the last second, after all the footage he shot vanished when the truck carrying it was stolen.) However, the most spellbinding sequence in the film—possibly of De Palma’s entire oeuvre—comes when Jack, using his audio recording and a collection of photographs of the accident published in a magazine a la the Zapruder film, creates a mini-movie that proves once and for all that it was anything but an accident. A scene like this in a contemporary film would be all but unimaginable, and not just because of the massive changes in technology—it has to go on for a while or else it simply doesn’t work. As shown here, it’s not only a completely spellbinding exercise in pure cinema but it also serves as beautiful and potent a display of the seductive allure of the filmmaking process as has ever been put up on the screen.

With the major exception of Sissy Spacek’s character in “Carrie,” De Palma’s characters were oftentimes essentially pawns that he moved around like chess pieces and whom it was sometimes difficult to relate to on an emotional level. Here, the central characters of Jack and Sally are both fleshed out and ultimately engaging despite their flaws, which not only allows viewers to develop an actual rooting interest in them but also gives the finale the overwhelmingly powerful punch that it might not have otherwise produced. Of course, the ability to care about these characters comes in no small part from the truly inspired performances behind them. For example, I don’t think that I am going too far out of line when I suggest that Travolta (who first worked with De Palma and Allen on “Carrie”) has made a number of films that are of a somewhat dubious nature—so many that while the aforementioned “Moment by Moment” was once regarded as a potential career-killer, it probably would not even rank among his ten worst films. However, one thing that you can say about him is that even in the worst and most ill-advised of his projects, you rarely see him simply coasting through a part—even in something like “Battlefield Earth” or “Gotti,” he is always putting in 100% effort. When he puts that approach in the service of a worthy screenplay and role, as is the case here, the results can be extraordinary. Beautifully suppressing the natural charm that helped make him a star but which would have been all wrong here, he plays Jack as a cold fish who has willingly removed himself from the world in order to avoid getting hurt and as he struggles tome the choice to care and reengage once again, he manages to engage viewers without breaking his character. Even though he is a mess, we still root for him and when it all goes wrong, we are just as shattered as he his in the film’s unforgettable final shot. This is by far the finest performance of Travolta’s career—even his turns in “Saturday Night Fever” (1977) and “Pulp Fiction” pale in comparison to it—and one of the biggest tragedies of the eventual failure of the film is that few people saw it at the time are realized what he was capable of doing.

The other key performances in the film are nothing to sneeze at either. When the film came out, there was much criticism that Allen (in what would be the last of the four films she did with De Palma, whom she was married to at the time) was merely playing a downscale version of the high-class sex worker she portrayed so memorably in “Dressed to Kill.” Like so much of the criticism of the film at the time, this observation was not entirely accurate and fails to take into account just how engaging and likable she is in the role—Sally may be a bit naive in certain regards but she is far from being just a mindless bimbo and, as is the case with Jack, we genuinely care about what happens to her during the breathless finale. More importantly, although the film smartly avoids any hint of a conventional romance between Jack and Sally, the onscreen chemistry between the two is off the charts, so much so that one can almost picture them taking those exact same characters and spinning them off into a potentially fascinating romantic comedy.

And since a film of the sort has a tendency to live or die on the strength of their villains, “Blow Out” is blessed with two equally strong performances in the bad guy roles. As the sleazy photographer, Dennis Franz (who had small roles in “The Fury” and “Dressed to Kill”) is an absolute hoot as a guy who suggests what might result if a stained T-shirt suddenly became a sentient life form. John Lithgow, who worked with De Palma on “Obsession” (1976) and would later reunite with him on “Raising Cain” (1992), is a scream of an entirely different and more chilling manner, as someone who suggests a cross between G.Gordon Liddy and the serial killer character that Lithgow would later play so memorably on “Dexter.”

In the wake of the failure of “Blow Out,” De Palma quickly signed on to do the splashy, big-budget remake of “Scarface” (1983). He continued with a career that would continue to raise the hackles of critics and audiences alike while hitting upon the occasional success with films like “The Untouchables” (1987) and “Mission: Impossible” (1996) that allowed him to channel his undiminished filmmaking skills into a more commercially viable framework. The one downside is that, with the exceptions of the war dramas “Casualties of War” (1989) and “Redacted” (2007), De Palma never really tackled material as serious-minded again, even though he proved himself more than capable of with it.

And yet, the reputation of “Blow Out” has continued to grow in the 40 years since it first came out. While the technological aspects have certainly changed, the story has not aged at all—in an era in which people are more willing than ever to find conspiracy in everything, it now feels more in sync with the times than ever before and even the infamous finale feels like less of a shock. It remains a work of stunning cinematic craft from one of our greatest, if too often undervalued, filmmakers and while he has made any number of other great movies over the years, this is the one he deserves to be remembered for above all.

“Blow Out” is now playing on the Criterion Channel.