Forget the Alamo: The Silver Anniversary of Lone Star

[THIS PIECE CONTAINS SPOILERS FOR “LONE STAR,” A FILM RELEASED IN 1996 THAT YOU REALLY SHOULD SEE.]

Released 25 years ago this week, John Sayles’ “Lone Star” is the director’s best film and the most wide-ranging and sophisticated drama ever set in Texas. And it is the movie that best understands how Texans mythologize and lie about themselves, and how the lying and mythologizing dovetails with deception and self-deception in the rest of the nation, and the world.

“Lone Star” is set on the border separating Texas from Mexico in the fictional town of Frontera. As the story unfolds, we keep returning to the concept of the frontier as precisely that: a concept, not a real, measurable thing. The idea of “the frontier” nevertheless defined the self-image of white settlers in the 19th century, and powered the next 150 years’ worth of Western fiction, films, and TV series, as well as works in other genres that are essentially Westerns in science-fiction, crime thriller, or action movie drag (see in particular the career of director Walter Hill, who has worked in all four genres but ultimately always makes Westerns.)

But “frontier” means something different to Native Americans, Mexicans, Mexican-Americans, and Black Americans who were either displaced from their land or prevented from owning land in the first place. To them, the word was not a promise, but a threat. The phrase Manifest Destiny was even scarier, because it meant the assimilation and conquering was ordained by a higher power. The word ‘border,’ likewise, can mean everything or nothing depending on who’s using it. As one “Lone Star” character points out, a bird flying from the US to Mexico doesn’t see, much less recognize, a border.

Sayles’ script starts out telling stories of white, Black, Mexican-American and Mexican people that seem to be unfolding along parallel lines, with rare points of intersection. But when you get to the end, you realize they were never really separate—that, in fact, seemingly independent, self determined lives were set in motion decades ago by actions of parents or ancestors that our main players barely knew (or were told lies about). The result is a web of interdependence that requires representatives of every major demographic group to compromise their values, initially for survival and then (after they assimilate and have children) for land, money, and comfort. The separations cease to be important except as arbitrary markers of power, and by the end of the movie, all boundaries dissolve, even those determined by race, culture, and family bloodline.

The film’s deep bench of characters includes Pilar Cruz (Elizabeth Peña), a schoolteacher with an at-risk teenage son; Pilar’s mother Mercedes (Míriam Colón), the owner of a thriving local cantina whose husband was murdered long ago under mysterious circumstances; Hollis Pogue (Clifton James), the town mayor who was once Buddy’s deputy; Delmore Payne (Joe Morton, star of Sayles’ superb race fable “The Brother from Another Planet”), an Army colonel who grew up in Frontera and has returned to run the local Army base; and Delmore’s father Otis Payne (Ron Canada), owner of Frontera’s only notable Black-owned nightclub, a center for African-American life in a part of the state where Blacks rank a distant third in the political pecking order.

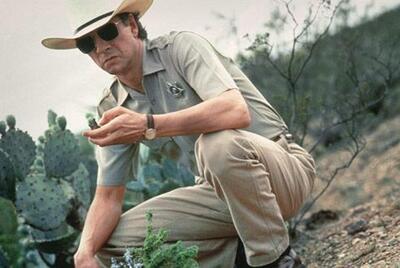

Our guide through the story is Pilar’s former flame, Frontera sheriff Sam Deeds (Chris Cooper, who became an indie film star playing a labor union organizer in Sayles’ 1987 drama “Matewan” nine years earlier). Sam is the son of legendary lawman Buddy Deeds (played in flashback by a then-unknown Matthew McConaughey), the only man who dared stand up to his corrupt and vicious boss, Sheriff Charlie Wade (Kris Kristofferson). Wade was a two-fisted, pistol-packing, racist grifter who ruled the town in the 1950s and ’60. He carried on like a mob boss, regularly demanding a cut of everyone else’s business, deliverable in cash. Anyone who complained, per “Goodfellas,” got hit so bad they never complained again.

Sayles has a genius for coupling textual and physical metaphors, and he opens this film with a doozy. A couple of sculptors who make art from bullets (as Sayles is about to do for the next two-plus hours, and as Western writers and filmmakers had been doing for more than a century) roam with metal detectors on a shooting range near the US Army base. The place doubles as an execution spot for local criminals. The range is described as a “lead mine,” as opposed to a gold mine, but narratively it’s both: in this grim stretch of desert, Sayles’ hybrid Western, film noir, and police procedural takes shape. The artists find a skeleton, a shell casing, a badge, and a Masonic ring. The bones belong to Charlie Wade, who disappeared on the night Buddy publicly stood up to him by refusing to accept a cut of his bribe money or serve as his bag man. Although other suspects are introduced, Sam’s gut feeling is that his dad is the killer. Every detail he learns while nosing around in places he’s not supposed to go confirms that Buddy was involved in the killing. It’s only a matter of figuring out what was at stake, and who else was complicit.

Sayles’ script simultaneously echoes classics of the Western genre (notably John Ford’s meta-Western “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” about the difference between truth and legend); film noir (the behaviors of both sheriffs echo the corruption of “Chinatown” villain Noah Cross, and there are revelations of the forced displacement of poor people by a land developer, as well as a dash of incest); and films and TV programs with an unabashed theatrical feeling. Sayles has been frank about wanting to kick his directing up a notch with this movie, following scattered complaints that his films were too much like illustrated versions of scripts or short fiction, and he achieves that goal and then some. Frontera is shot and portrayed in a naturalistic, understated, “Western-movie” sort of way, the whole “aw, shucks, t’weren’t nothin'” vibe. But Sayles’ direction also permits hints of expressionism and magical realism, and he and his cinematographer, Stuart Dryburgh, convey time shifts in in-camera without cuts or dissolves, re-framing to reveal characters from the past or present, depending on what direction time happens to be flowing in.

Still, though, “Lone Star” is careful not to overdo anything, as if safeguarding against the inherent tendency for oversimplification and overstatement in a screenplay that’s very much about mythmaking, storytelling for power and profit, and how the persistence of one narrative often has more to do with who’s behind it than how convincing it actually is. It’s all theater: political theater, emotional theater. The idea of The Public Stage has rarely been more cogently presented. Sayles embraces the idea of Frontera as a gigantic theater set where actors banter through expository revelations and segue into monologues. The latter are often treated as verbal spectacles that don’t require flashback imagery to get their points across. Sayles seems to have adopted Ingmar Bergman’s belief that a great face is all you need.

There’s a sawdust-and-footlights feeling to the characterizations and performances—particularly the ritualized confrontations between men that threaten to erupt into lethal violence, the camera recording live-wire threats from angles that mimic the perspective of a theatergoer looking slightly up at performers on a raised stage. Like the towns in “Liberty Valance” and Wilder’s “Our Town,” and the city blocks in “Dog Day Afternoon” and “Do the Right Thing” (as well as Sayles’ very Spike Lee-ish 1991 urban drama “City of Hope”), the film feels real and not-real at the same time. The characters are credible as persons who could exist, but also (and how amazing that this is not a contradiction!) as delivery devices for clashing views on political and historical reality, moving viewers through a tale that is, in basic and undeniable ways, a play of ideas.

What makes “Lone Star” feel honest and timeless is its insistence that all of these characters in this corrupt Texas town are just human beings, and that when they act in cowardly, acquisitive, or treacherous ways, they are behaving in accordance with their conditioning, in ways they may not consciously understand. The presentation of Charlie Wade at first feels overcooked, or out-of-sync with the other major characters, because his villainy is so outsized, and he relishes performing it to terrify others (Kristofferson never really got his due as an actor, and this is one of his best performances, oozing racial entitlement and smug nastiness). But we come to understand that this, too, is part of the film’s design. Through the investigations of Sam and his allies, we learn that Buddy was not actually the antidote to corruption, but incarnated a more socially acceptable form of it, in much the same way that the supposed “civilization” of the “frontier”—a major theme in the Western—was a convenient cover story, obscuring how subjugation, bigotry, and rampant greed backed by violence all became institutionalized, subsumed into the normal operations of governments and corporations.

Buddy, it turns out, took a piece of others people’s action, like Charlie before him, just not blatantly. Envelopes of cash never changed hands, as far as we know, but Buddy as mayor apparently didn’t see a problem with taking a piece of a real estate development that used eminent domain to seize other people’s land. Nor did he have a problem with using a prisoner on work release to build a deck onto his home for no pay. More important to Frontera and Buddy, in the long run, was the new sheriff and future mayor’s skill as a coalition builder and kingmaker, securing the political support of Chet Payne and Mercedes Colon by discouraging other businesspeople of color from opening establishments that might compete with theirs. The script establishes early that Sam is opposed to building a new prison in Frontera because the town already profits from the state renting local jail cells (Sayles was ahead of the curve in warning audiences against the burgeoning prison-industrial complex). When his Mexican-American chief deputy Ray (Tony Plana) asks his blessing to run for sheriff when Sam’s term expires (something that we gather was going to happen no matter what, and that was engineered because the town power brokers were tired of Sam back-talking them) Sam asks him what he thinks about the idea of building a new prison. “It’s a complicated issue,” Ray says, clearly embarrassed at having to admit his spinelessness. “Yeah, Ray,” Sam says, “you’ll be a hell of a sheriff.”

There are always three or four things going on in every scene of Sayles’ script beyond the delivery of plot information. One of the most unexpected and rich is the notion that most major decisions in Frontera—as in Texas, and the United States generally—are driven by ideas of whiteness and white exceptionalism, even though the idea of “whiteness” is as much an agreed-upon lie as the idea of a border. It’s provisional, for one thing, and once it is granted to a person not previously described that way, it can be swiftly revoked if an individual fails to toe a certain line. Whiteness, as presented here, is about a willingness to join the existing power structure, whatever it is—and go along to get along. It doesn’t protect a person completely, but it helps.

Tony is one example of that principle. Another is Mercedes, who came to the United States as an undocumented immigrant but refuses to employ “wetbacks” and calls border patrol when she sees illegals on her property. There is some dialogue suggesting that Delmore Payne’s decision to join the US Army—a racist institution for much of its existence, both in terms of how it exercised force against other cultures and how it treated its own nonwhite members—represents a capitulation, and that he’s trying to break the spirit of his son Chet (Eddie Robinson), setting the stage for oppressive behavior to repeat itself. What is the history of Texas, and by extension America, Sayles suggests, but that of generations of undesirables climbing the ladder to success any way they can, then pulling it up behind them?

That this film’s insights come from a filmmaker born and raised in Hoboken, New Jersey, seems less like an irony than an inevitability. If you take the stereotypical boastful, bigger-than-life Texan at their word, and accept that Texas not only used to be its own country (the cowboy myth of self-reliance and reinvention applied to an entire US state) but still believes that it is one, that would make Sayles a foreigner. And if there’s one thing that the history of art has taught us, it’s that sometimes it takes a foreigner to cut through all the bullshit and show us the truth about a place.

I don’t use the word “us” lightly. Before I was a New Yorker, I was a Texan—specifically a white Texan, a distinction that’s crucial to understanding what Sayles is doing in “Lone Star.” Being a white Texan means being indoctrinated with an official self-image of what it means to be a white Texan. Despite occasional shamefaced apologies and self-chastisements, the white Texan is the only kind of Texan to whom the image of The Texan—the soft-spoken tough guy with the ten-gallon hat and six-shooters and square jawline, standing up for truth and justice and independence—truly applies. The ground shifted a little bit in 1981, when the demographics of South Texas allowed the election of Henry Cisneros, a Mexican-American, as the first nonwhite mayor of San Antonio. (The last time a person of color held that job was 1942, when Juan Seguin, a Tejano-Spanish military and political figure who sided with the breakaway Texans in their fight against Antonio López de Santa Anna.)

I spent over 20 years of my life in the Lone Star state, a part of the former Confederacy, and I can testify to the level of indoctrination that every Texan of every color received through the educational system and popular culture until pretty recently. State law required a semester of Texas history for all middle schoolers, and again in high school. “History,” alas, meant white supremacist propaganda. My textbooks taught my schools’ racially diverse student bodies that even though slavery was wrong, the Union’s violation of the concept of “State’s Rights” (i.e., the right to own other human beings, though the books were careful not to dig into that) was somehow equally wrong, and that it was hurtful and incorrect to describe Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States of America, as a traitor, because from his point-of-view, and the points-of-view of people who supported him, the Union was cruel and tyrannical.

Students of my generation were also taught that it was wrong for the Union to “punish” the South after it lost the war (though, as even a cursory study of Reconstruction easily demonstrates, there wasn’t all that much “punishment” against traitors compared to what has happened in other countries where parts of the population tried to break away and form their own country. And former Confederates quickly figured out ways to disempower former slaves who had been briefly empowered, eventually leading to Jim Crow laws, which didn’t begin to be seriously challenged until the Civil Rights marches of the 1950s and 1960s. In regular US History courses, I learned that the Radical Republicans, who wanted legally-enforced freedom and agency for former slaves, were the bad guys in the post-Civil War period; and that president Andrew Johnson, an obstructionist of racial progress, was vilified for daring to undermine them, and never got a fair shake. In the U.S.-Mexico war, according to official Texas history books, Mexico was the bad guy, white “settlers” who had claimed portions of Texas for themselves were the good guys, and the battle of the Alamo represented a heroic act of defiance against the intransigent, control-freak dictatorship of Santa Ana. It wasn’t until university that I learned about complicating factors that conveniently got left out of my earlier studies, such as the fact that many white Texans wanted to break away from Mexico because Mexico refused to allow the importation of new slaves after 1830.

All this information likely meaningless to anyone from outside the United States. But hopefully it gives some sense of what sort of “history” was being taught in Texas schools in the late 20th century, and the way in which official history tends to get shaped and reinforced and passed down in civilizations all over the world, past as well as present. With its plainspoken understanding of politics as theater and history as myth, “Lone Star” should be taught in Texas schools alongside the official texts. Let the books tell students to remember the Alamo, and let “Lone Star” tell them to forget it.