10 years after Deepwater Horizon — what has science learned from the spill?

Ten years after one of the largest environmental disasters in American history, oil spill science is better and stronger — but there are still many unanswered questions about the effects of the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

“It’s a good news story in the sense that 10 years later we know a lot more, we are better prepared for the next eventuality,” marine geochemist Elizabeth Kujawinski told Quirks & Quarks host Bob McDonald. “It’s a bad news story in the sense that we don’t entirely know everything that happened.”

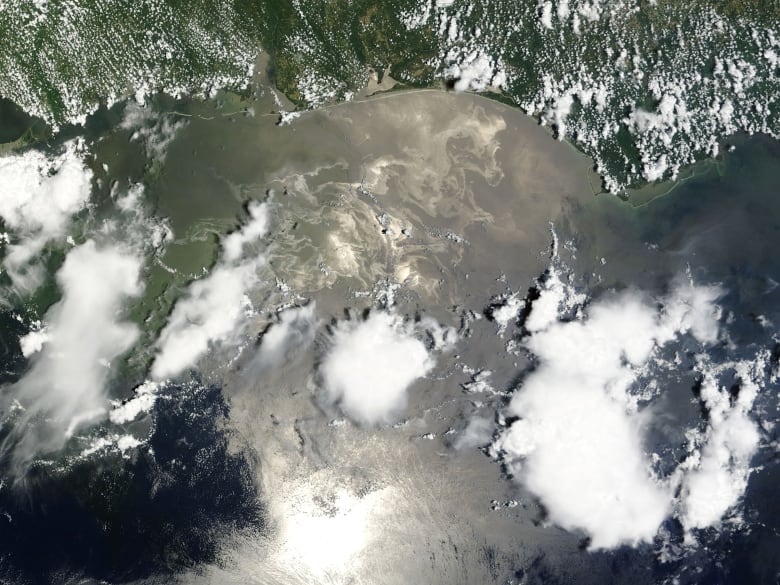

On April 20, 2010, a powerful explosion at an oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico killed 11 workers, and injured 17 others. That explosion also resulted in an oil well blowout more than a kilometre underwater. Crude oil flowed from that well into the ocean for the next 87 days.

In all, the Deepwater Horizon oil well disaster released an estimated 800 million litres of oil and gas into the Gulf of Mexico, making it the largest accidental marine oil spill in history.

Kujawinski is a Senior Scientist in Marine Chemistry & Geochemistry at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is part of a team behind a review paper, published this week, which surveys what scientists have learned from studying the spill over the past decade.

Deepwater Horizon as one big science experiment

While the oil spill was devastating, it did enable significant scientific discoveries. One such discovery is the greater understanding of how bacteria are involved in degrading oil and gas released into the ocean.

“So who responds first: the organisms that eat oil, or the organisms that eat the gas?” said Kujawinski.

Another lesson learned was the role of the sun in breaking down the oil. Because the spill took place during the summer months, the strong sunlight acted as a further catalyst to breaking up the oil.

“That has generated a really interesting body of work that can be used for future spills to understand how to promote that kind of degradation, how to promote sort of the ecosystem cleaning itself,” she said.

As to how the ecosystems are recovering, Kujawinski says some areas are doing better than others. “We were pleasantly surprised… Different Marsh systems and certain aspects of the deep sea all seem to be recovering.”

However, other areas have not bounced back as quickly.

“That seems to be a function of the fact that the Deepwater Horizon was just one of many stressors that were hitting that ecosystem at the time.”

All of this data goes into creating more accurate models to tell scientists how to deal with oil spills in the future.

Dispersants — did they help, or did they hurt?

There are still many unknowns about the lasting effects of the spill — including the effects of the tools used to stop it.

In an attempt to get the massive spill under control, emergency teams used over 3 million litres of chemical dispersants, which were meant to break up the oil and make it easier to biodegrade. At the time, such widespread use of dispersants was controversial, especially because they were being applied directly to the well head, 1.5 kilometres underwater.

“The dispersants in my opinion remain one of the most complicated and difficult to understand components of the Deepwater Horizon,” said Kujawinski. “One of the reasons it was a big concern was because there had not been any study of how dispersants would affect organisms, whether they are corals or fish or dolphins or whales in the deep ocean.”

At the time, Kujawinski studied the chemistry of organic molecules in seawater, and was studying the impact that the dispersants, as well as the oil and gas, would have on the organic molecules in seawater.

“We know that there were dispersants down in the deep ocean for a longer period of time than might have been originally intended,” she said.

But they don’t know what effects those dispersants are having in the deep ocean. “You have to be able to know what the oil droplets look like coming out of the wellhead before the dispersant, and then during the dispersant application, and those were very challenging data to get,” she said.

“In the future, it is now clear that that is the critical data to have.”

In all, as unfortunate as the disaster was, the science community is now better armed to deal with future oil spills, wherever they may be.

“Our biggest concerns with the Deepwater Horizon results is what will happen if this happens again, but in the Arctic,” she said. “It’s much colder, it’s much more remote, the weather is much more severe.

“In many respects the Deepwater Horizon, as awful as it was, was a way for us to figure out what’s really happening in these systems without the worst case scenario.”

Written and produced by Amanda Buckiewicz