'Going to jail is probably easier': Domestic violence perpetrators tout treatment program

This story is part of Stopping Domestic Violence, a CBC News series looking at the crisis of intimate partner violence in Canada and what can be done to end it.

“How do we stop being hamsters?”

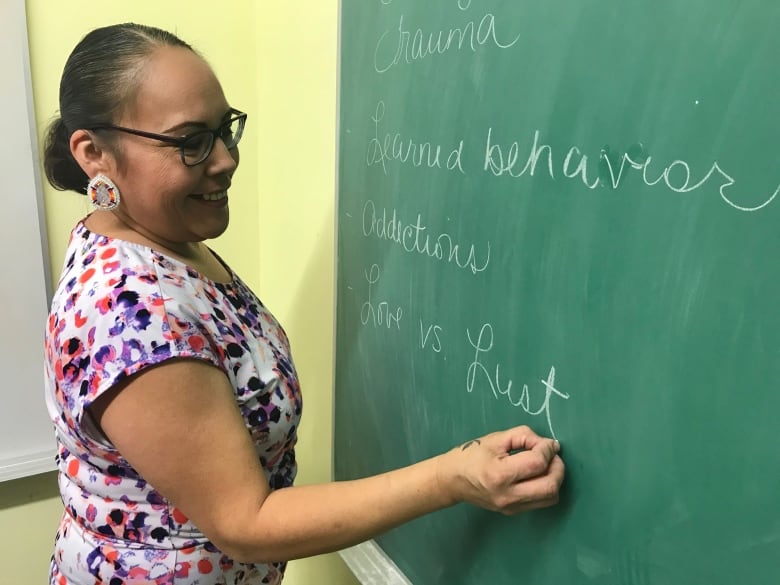

Probation officer Pam Desnomie wants to get a laugh, but she also wants to make a point.

As night falls in the Qu’Appelle valley, east of Regina, the no-nonsense Cree woman poses that question to eight men and three women who have all been charged with some kind of domestic violence.

Desnomie, 59, believes most perpetrators of domestic violence learn the behaviour as children and repeat it as adults, like hamsters going round and round on a wheel.

“What are you going to do to break the cycle?” Desnomie asks the group.

Desnomie’s day job is supervising offenders serving sentences in the community, but she volunteers to facilitate this two-hour session every Monday night because it gives her hope.

Most of the men and women have been ordered by a provincial court judge in Fort Qu’Appelle to take The Way, a 52-week domestic violence intervention and prevention program offered by the File Hills Qu’Appelle Tribal Council. The council also delivers the program on four reserves and inside the provincial jail in Regina. Participants are primarily First Nations men who also have drug or alcohol problems.

Saskatchewan has one of the highest rates of intimate partner violence in the country. A CBC News analysis has revealed women and children fleeing violence are turned away from domestic violence shelters more than 600 times a month in Saskatchewan and tens of thousands of times a month nationally.

‘It’s preventable’

“Domestic violence is predictable, and if it’s predictable, it’s preventable,” said Bev Poitras, the tribal council’s director of restorative justice.

Poitras has been the driving force behind The Way. It began when Peepeekisis First Nation realized 80 per cent of criminal charges in the community were related to domestic violence.

Poitras decided that helping abused women and children flee violence wasn’t a long-term solution.

“The police go to the home, they’ll separate the husband, take him away. The wife goes to the safe shelter … within two days, two weeks, two months, they’re back together again,” Poitras said.

It makes more sense to try to heal families, she concluded.

Poitras wrote proposals and got nearly $300,000 from the federal government to build the program and train facilitators.

The curriculum combines feminist theory about power and control with cognitive behaviour therapy to teach abusers how to control their behaviour, attitudes and choices in order to build healthy, non-violent relationships. Sessions include such topics as triggers of violence, substance abuse, power sharing and forgiveness. Over time, facilitators have folded in traditional Indigenous teachings.

The Way invites both offenders and their victims to participate, if it’s considered safe. The local judge will often waive a no-contact order for the brief period when they’re in a session together.

Jail versus therapy

Tonight’s lesson is about intergenerational patterns of violence.

Desnomie asks the group what kinds of abuse they witnessed in their childhood home and how it made them feel.

“Scared.”

“Ashamed.”

“Unloved.”

Desnomie responds, “You bring all that garbage into your relationships.”

It’s mind-blowing. We see the progression and them actually taking that responsibility for what they’ve done.– Pam Desnomie, facilitator, The Way

It’s overwhelming for Angela Morin, 39, a mother of seven who lives in Fort Qu’Appelle. She grew up in a home filled with alcoholism and abuse of all kinds: physical, sexual, mental and emotional. Morin says she spent a decade getting beat up by her husband and only left the relationship after her children were apprehended.

Now, in a new relationship, she’s the one who lashed out in anger. Last year, Morin pleaded guilty to assault after a drunken fight with her boyfriend. The judge ordered her into The Way and gave her a conditional discharge, with no criminal conviction or record.

“I’m learning a lot about myself, who I am, and how not to repeat this in the future,” said Morin, who is still with her boyfriend despite the assault.

This doesn’t mean offenders are getting off lightly, Poitras said.

“What is real punishment? Right? Because to me, having to deal with the traumas and the garbage that you’ve learned, and things that are not appropriate, that’s hard. That’s hard to change that. So, going to jail is probably easier,” Poitras said.

Jason Bear, a 42-year-old from Ochapowace First Nation, avoided jail time by taking the program. He was charged with unlawful entry last year after he got drunk and broke into his ex-wife’s house to retrieve some of his belongings. He didn’t attack her, but the judge could see Bear had a history of violence and ordered him to take this year-long program.

“It definitely hit home, and it hit the heart,” Bear said about the treatment program. “You get out what you put into it.”

He used to blame his parents. He grew up in a home with a toxic and violent mix of alcohol and abuse, he says, and he thought that was “normal.”

Now Bear, who has a new partner, believes it’s possible to change.

“I’ve taken responsibility for all of my actions leading up to now,” Bear said.

Does it work?

The Way has a lot of support and testimonials, but no evaluation results to back it up.

Batterer intervention programs (BIPs) can be controversial. There are several different kinds in North America. Studies about their effectiveness and how often perpetrators re-offend have produced conflicting results.

Critics suggest offender treatment programs can jeopardize victims’ safety by luring them back to their partner with a false sense of trust and security.

Crystal Giesbrecht, the director of research for the Provincial Association of Transition Houses and Services of Saskatchewan (PATHS), says she wants to see “programming for perpetrators that is based on evidence, that is rigorously evaluated, so that we know that it’s doing what we hope it’s doing.”

She doesn’t believe a one-size-fits-all program will work for every offender, or every community.

The Government of Saskatchewan is partnering with File Hills Qu’Appelle Tribal Council to figure out how to formally measure the impact of The Way and whether graduates have re-offended.

In the spring of 2019, the Ministry of Corrections and Policing began offering incarcerated high-risk offenders a program designed by U.S. correctional treatment experts. The province plans to evaluate this program, as well, to assess its impact on recidivism.

Offenders who plead guilty in specialized domestic violence courts in Regina, Saskatoon and North Battleford can also take a court-monitored counselling program.

“Formal evaluations of these courts show that treatment programs have an impact on positively changing offender attitudes and behaviours, and that victims reported feeling safer,” according to a statement from the provincial Ministry of Justice.

Culture and connections

Much of the strength of The Way can’t be written in a textbook. It’s about connection, culture and community.

Desnomie and her co-facilitator, Frances Elliott, laugh and joke with the group to relieve pressure as they grind their way through tough conversations about childhood trauma.

There’s a common understanding that everyone in this room has had shared experiences.

Desnomie was only 13-years old when she was first hit by a boyfriend. He was older — 18 years old — and worked in the kitchen at her residential school. She got pregnant and was pressured to stay in an abusive relationship that would last for years.

Nearly four decades after leaving him, she can still remember the feeling of having no power or control.

These sessions are part of her healing journey too.

“It’s mind-blowing. We see the progression and them actually taking that responsibility for what they’ve done. On average, it takes three or four months before they get it and it clicks in, but we just stick with them,” Desnomie said.

She gives everyone a homework assignment for next week:

Brainstorm five non-violent behaviours you will teach your children.

If you need help and are in immediate danger, call 911. To find assistance in your area, visit sheltersafe.ca orhttp://endingviolencecanada.org/getting-help. In Saskatchewan,www.pathssk.org has listings of available services across the province.