B.C. First Nation signs historic water agreement with company that flooded it decades ago

Almost 70 years after the Cheslatta Carrier First Nation was destroyed by fire and floods, to make way for an industrial project, the community has signed a deal with the company that was responsible for the destruction.

In 1952, members of the Cheslatta Carrier Nation in northern British Columbia were forced from their homes with only two weeks notice so that Alcan, a mining company, could make way for a hydrolectric dam and its reservoir to power the nearby aluminum smelter in Kitimat.

In the following weeks, the floodwaters rose, destroying the community as well as 60 graves of community members.

On Thursday, Cheslatta Carrier First Nation signed a deal with the mining company, now named Rio Tinto, to work together and rebuild the First Nation’s economy through a land transfer, a scholarship fund, a training centre and promotion of recreation and tourism.

In 2019, the B.C. government promised to pay the First Nation more than $4 million in restitution.

Corrina Leween, the First Nation’s chief, spoke with As It Happens guest host Helen Mann about how this deal represents a “new relationship” with the mining company. Here is part of their conversation.

Maybe you could start by taking us back to 1952, and tell us what happened — what people were told when they got this notice that they were to pack up and leave.

There were representatives from the Department of Indian Affairs (D.I.A.) and the Rio Tinto Alcan — Alcan at the time — representatives. And they came into the community and had meetings with the people — basically told them that they had to leave, that the water levels were going to rise.

So with a couple of days notice the people packed their bags, and what they could carry, and left the area. They were given two weeks notice.

Where did they go?

They walked out of the Cheslatta area, and they headed into the Grassy Plains area. And currently, our community resides spread out from the Marilla area — which is the Ootsa Lake area — all the way over to the Uncha Lake area. And it’s mainly the Grassy Plains area and the Uncha territories where our people live.

What happened to these homes after they were left?

So when the Cheslatta people left, they were burned down. And before they left, they buried some of their possessions so they could come back for them. The company used — or D.I.A. used — metal detectors, and found where they had buried some of their possessions. And they put them in a big pile, and they burnt them as well.

So when the people went back, that’s what they went back to. Their homes were gone.

“We called the agreement the New Day Agreement. And it was a willingness, I think, on both sides to create a partnership where we could work hand in hand. And work toward an economic solution to the poverty — to work toward a benefit agreement that would sustain all of our wishes and our gaps that we have in our community.” – Corrina Leween

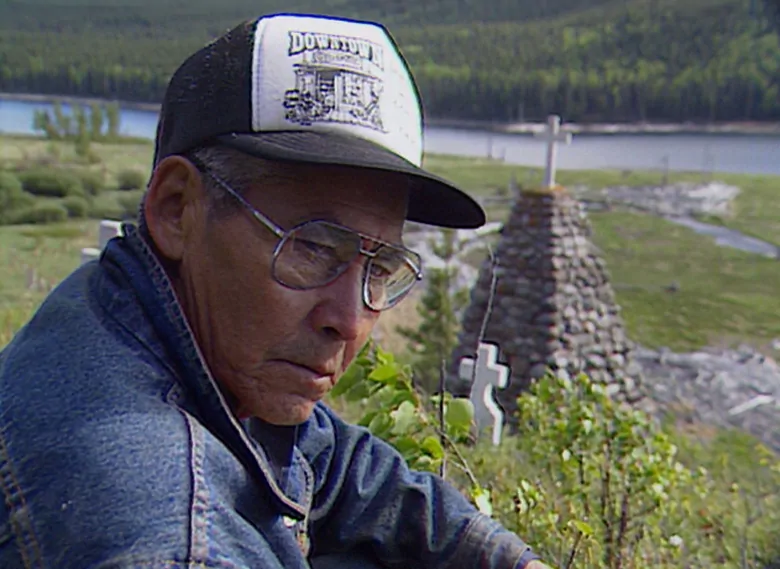

And you had a cemetery in the area. What happened there?

When the water started to rise, the people tried to relocate some of the people that were buried in the cemetery to higher grounds.

But the cemetery actually ended up washing a lot of our people into [the] Cheslatta water system — to the point where in a celebration the bishop came back down … and blessed the lake, and designated it as a cemetery.

And is it true that some people have actually found human remains?

Yes. It was only a few years ago that there was a camper at the Cheslatta Lake area. And he was camped on the beach, and he noticed what he thought were human bones protruding out of the bank. So he called Cheslatta office.

We all went down, and we had an archaeologist with us. And they uncovered the ground, and they found [an] elderly woman buried there. We called her Grandma Cheslatta.

This is not like an ancient grave site. This is just before 1952. So presumably families there might even know some of the people who are washed out of those graves. I’m wondering what kind of effect that has on a community.

It’s traumatizing every single time a new piece of their ancestors is found floating in the water. There’s been baby caskets — just the top of the baby casket, you know, floating in the water. And these are people that bring these back to Cheslatta when they find them. One elder said, “I don’t want to see that again, because it’s too hurtful.”

So it opens the wounds all over again each time this happens — each time the flooding happens and more of our people are found floating in the water, up on shore.

Why is it significant after all these years for Rio Tinto to come to some sort of settlement with your community?

We had called Rio Tinto to the table. It was a memorandum of understanding — started our whole process. And we wanted to create the partnership. We knew we are staying here. We knew Rio Tinto was going to stay here. So we went to the table.

We called the agreement the New Day Agreement. And it was a willingness, I think, on both sides to create a partnership where we could work hand in hand. And work toward an economic solution to the poverty — to work toward a benefit agreement that would sustain all of our wishes and our gaps that we have in our community.

So we wanted to rebuild our economy, stabilize our cemeteries, re-establish our community with better housing, better education opportunities. And we really wanted to create a stable environment for the economy.

And my generation — I’m the first generation coming out of there — that our generations can take and make a benefit out of what has happened to our earth, our children.

So that we can create that sustainability — where we’re in the driver’s seat, where we’re not going to be taking the handouts. We don’t want handouts anymore. What we want to do is rebuild our community.

Written by Sarah Jackson and Kevin Ball. Produced by Alison Masemann.