Artifacts recovered from HMS Erebus offer tantalizing links to sailors on doomed Franklin Expedition

A toothbrush. Human hairs caught in the bristles of a hairbrush. A fingerprint preserved in sealing wax.

Underwater archeologists from Parks Canada found these highly personal items as they recovered more than 350 artifacts during their most recent — and they say most successful — season yet at the HMS Erebus wreck site off the coast of Nunavut.

And they are hoping such tantalizing links to individual sailors from the mid-19th century British expedition led by John Franklin will offer clues and help them move closer to understanding what happened on the ill-fated polar mission.

Along with work done at the site of the other Franklin Expedition vessel — HMS Terror — the underwater excavation on Erebus late last summer was in many ways the result of several years of archeological preparation after the wrecks were discovered in 2014 and 2016.

“Through the work we did on Terror and being able to look inside the cabins, and now getting into the artifacts of individuals inside Erebus, this is the beginning — and it’s only the beginning — of really getting into the story in depth,” Marc-André Bernier, manager of Parks Canada’s underwater archeology team, said in an interview.

Some of the artifacts recovered from the wreck lying in the shallow waters of Wilmot and Crampton Bay were unveiled Thursday at Parks Canada’s conservation laboratories in Ottawa.

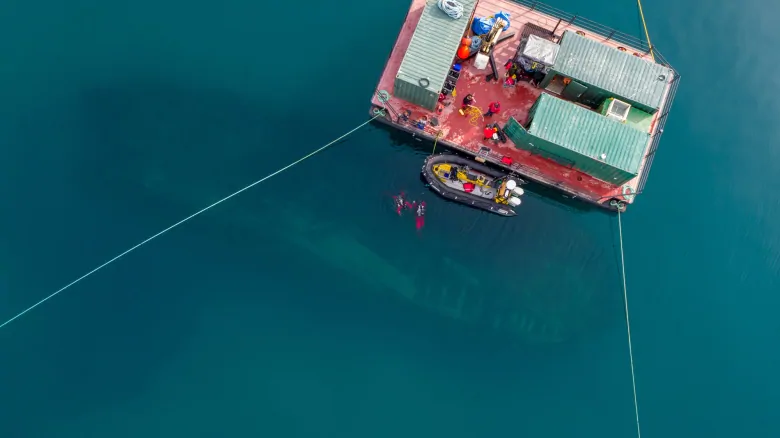

Over a three-week period in late August and September, members of the underwater archeology team made 93 dives and spent about 110 hours underwater at the Erebus site.

“It was by far our most successful season and we’re pretty excited,” said Bernier.

The experience was in marked contrast to their efforts the year before, which were severely hampered by miserable weather.

In 2019, however, the weather was “sublime,” senior underwater archeologist Ryan Harris said in an interview.

“One of our biggest challenges is just … environmental conditions in the central Arctic. We can come up with the most detailed, well-laid plans and they can be frustrated by very unco-operative ice conditions and weather,” he said.

“Finally in 2019 … [it] all came to fruition. It’s extremely gratifying for the entire team.”

Erebus and Terror set sail from Greenhithe, England, in 1845 in an expedition led by Franklin in search of the elusive Northwest Passage.

The ships were beset by ice off King William Island in 1846 and deserted two years later, according to a note left by the crew in a cairn. Franklin and his 128 men all died.

But what really happened on the expedition has been an enduring mystery. The discovery of Erebus in 2014, and Terror two years later, in many ways only raised more questions, particularly regarding how the ships ended up where they did.

This past season marked a major transition in the exploration of the Erebus site, as archeologists moved from assessing and evaluating it to meticulous and systematic excavation inside the wreck.

“We have always said … that the potential to find things is great because of the cold water [preserving artifacts]. But this year, that was confirmed,” said Bernier. “We are finding places that have not been displaced or moved since the ship went down.”

‘It’s quite humbling’

In this instance, archeologists focused efforts on the living quarters of the crew on the lower deck of the ship, diving about eight metres below the surface of the water.

“We’re excavating in the world of somebody that lived 170 years ago in his space, so when you go down it’s quite humbling … but it’s exciting,” said Bernier.

“Every day, every dive is a discovery. You just don’t know what to expect.”

Items recovered included epaulettes from a lieutenant’s uniform and ceramic dishes. The epaulettes, Bernier said, were found in a drawer filled with a lot of sediment but otherwise empty of artifacts, leaving the impression that they were abandoned.

“On the flip side, in the ship’s pantry, there’s barely any sediment, because the density of the objects is so big. You would have plates stacked up 13 high.”

Other items recovered include a leather coat sleeve, textiles, navigational instruments, buttons, an entire table service for the captain’s table and a ceramic jar with “prepared mustard” stamped on it and mustard seeds inside. Quite a few bottles were found — “10 or 12 of the wine bottle type,” Bernier said.

“Some still had contents in it, so we’ll have that analyzed.”

There was even an accordion — after the years underwater, it doesn’t play, but does allude to how the sailors brought along items to entertain themselves.

While human hairs were found on the hairbrush, no human remains have been discovered on Erebus so far.

Numerous writing materials — a wooden pencil case, four kinds of pencils and a quill with a full feather and a pointed end — were also discovered. But no logs or diaries that might contain sought-after accounts of what happened during the expedition have been found.

“That’s the next step, we hope,” said Bernier, who also noted such materials might be more likely found toward the ship’s stern, in officers’ cabins.

In the Erebus pantry, archeologists found a lead stamp with a name on it — that of “Ed. Hoar,” steward for the ship’s captain. Edmund Hoar, from Portsea, Hampshire, was 23 when the expedition set sail in 1845.

Such personal discoveries hold a particular significance for the archeologists.

“Whenever in archeology we come across artifacts that can really be linked to individuals, that’s highly personalized, that’s quite evocative,” said Harris. He also pointed to the sealing wax that has the thumbprint or fingerprint of the sailor who used it to seal a letter or document.

“We talked about trying to identify DNA samples, but to actually have a fingerprint from one of the crew, that’s incredible, something you just don’t come across every day.”

In the case of Hoar, who wasn’t an officer on the ship, the discovery of his name and its association with an artifact offers the opportunity to tell the tale of someone of a more humble origin.

‘That’s where archeology is in the best position to tell the story of people who don’t have as much of a presence in the historical record,” said Harris.

“The sailors themselves had to fit all of their earthly possessions into one half of a seaman’s chest that would double as a bench at the mess table.

“We’re not just interested in telling the stories of the officers who had an elevated social status, but of the more anonymous people that made up the rest of the ship’s company.”

Harris said they are trying to tell the story of the expedition on many different levels, from the overarching historical narrative right down to the experiences of individual crew members and who was in a particular cabin at a particular time.

“What are the events we don’t know about and what order did things unfold in? Why are the two ships 75 kilometres apart? How did they sink?” Harris said, rhyming off some of the questions that have been at the core of the Franklin mystery.

“Who were the final survivors of the expedition? Did discipline break down or was it maintained until the end? Those are the sorts of stories we hope to tell with artifacts that are linked to specific individuals.”

While the archeologists are revelling in last summer’s results, they won’t offer any public assessment of how what has been found might contribute to answering bigger questions hanging over the Franklin Expedition.

Watch: Video footage from the wreck of HMS Terror

It’s “all too early to say,” said Harris.

“You definitely run a risk if you try to arrive at conclusions with only a handful of artifacts, but I think what we have at hand now is a confirmation of the density and diversity of artifacts that we stand to find in subsequent field seasons.”

Bernier said it’s “been a long road” to get to this point in trying to tell the story of the Franklin Expedition.

“We hope this is the beginning of a long string of seasons where we actually get into the story.”