Liberals postpone planned tabling of UNDRIP bill because of Wet'suwet'en crisis, says Mohawk chief

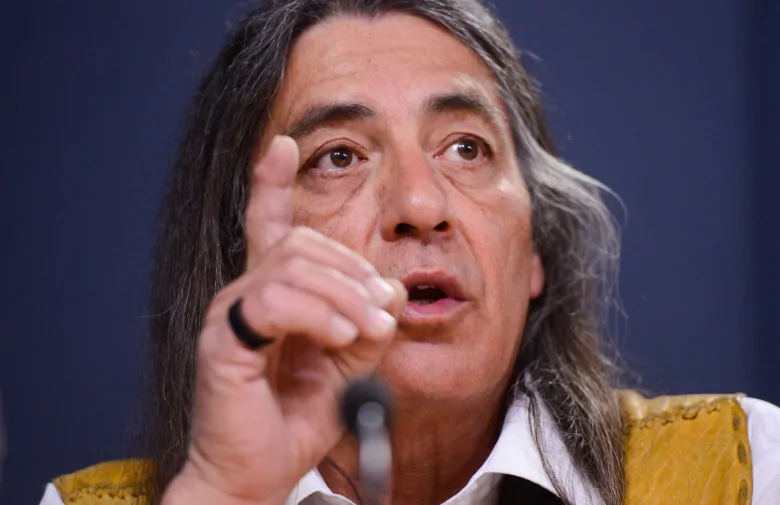

The Liberal government has postponed a planned tabling of its promised bill on the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as a result of ongoing rail blockades sparked by RCMP action on Wet’suwet’en territory, according to Kanesatake Grand Chief Serge Simon.

Simon said he learned of the decision on Tuesday when he went to Ottawa to appear at a news conference alongside Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde and the band chiefs from the Mohawk communities of Kahnawake,Tyendinaga and a former chief of Akwesasne.

“My understanding is that because of this crisis that the Trudeau government has to deal with they will have to put the UNDRIP aside for now,” said Simon, whose Mohawk community west of Montreal was at the centre of the 1990 Oka Crisis.

“Hopefully that is not the case…It could be a means for this situation to get resolved, if Trudeau … continues with what he has promised, that would show a lot of good faith.”

On Feb. 6, B.C. RCMP began enforcing an injunction against Wet’suwet’en encampments that were built to stop construction of a natural gas pipeline. This led to protests and rail blockades across the country — including one demonstration that has paralyzed one of Canada’s busiest rail corridors.

CBC News has learned that national Indigenous organizations were alerted last week that the Trudeau government would be tabling the bill on the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) on Thursday

UNDRIP establishes minimum standards for how countries should deal with Indigenous Peoples. In its throne speech late last year, the Trudeau government promised to have the legislation introduced within a year.

Officials with Indigenous organizations were informed on Monday that tabling of the bill would be postponed and that no replacement date had yet been set, according to the source.

Justice Minister David Lametti’s office has the lead on the UNDRIP file. A senior government source told CBC News the government remains committed to UNDRIP and to tabling legislation to implement it soon.

Ontario rail traffic stopped for 2 weeks

The bill has been postponed amid an unfolding national crisis that hangs on a breakthrough at the table between the federal and B.C. provincial governements and the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs.

The RCMP action on Wet’suwet’en territory led Mohawks in Tyendinaga, Ont., to launch a demonstration along railway tracks between Napanee and Belleville, Ont., about 250 km west of Ottawa, that shut down a rail corridor vital to the movement of goods between eastern and western parts of the country.

The Mohawks say they won’t leave the rails until the RCMP pulls out of Wet’suwet’en territory and they have held their positions for two weeks.

An Ontario Superior Court injunction, which was extended last Friday, hangs over the demonstration and the Ontario Provincial Police are monitoring the Mohawk camp.

In B.C., the RCMP there said they discussing the request from the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs that they leave the territory.

“Discussions are underway with respect to possible next steps,” said B.C. RCMP Staff Sgt. Janelle Shoihet in a statement to CBC News.

“Any options will have to be discussed with all stakeholders and out of respect for those discussions, we have nothing to publicly share at this time.”

Wet’suwet’en hereditary Chief Woos told CBC’s Power and Politics Tuesday that he won’t meet with the federal or provincial governments until the RCMP leaves his territory. Woos wants a detachment set up by the RCMP in January 2019 removed from his Gidimt’en clan’s lands.

The Trudeau government, along with the B.C. government of John Horgan, are working on establishing talks with the Wet’suwet’en hereditary leadership. As of Wednesday morning, no date had yet been set for a meeting.

B.C. was the first province to pass UNDRIP legislation.

The Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs oppose the Coastal GasLink pipeline and say its approval for construction violated their recognized rights over the territory.

While several Wet’suwet’en band councils signed deals for the project, the hereditary chiefs say they have jurisdiction over the nation’s territory and point to a 1997 Supreme Court decision as supporting their position.