Oilsands on 'collision course' with Canada's climate goals, global market changes: report

The oilsands have reduced the amount of greenhouse gas they emit per barrel of oil produced but remain more carbon-intensive than the average barrel worldwide and are the fastest-growing source of emissions in Canada, according to a new report from the Pembina Institute.

That puts the sector in a risky position as the world looks to shift toward lower-carbon energy sources, the report says, and creates a challenge for Canada in meeting its climate commitments.

“We urgently need to work together to prepare Canada to compete in a low-carbon economy,” the institute’s executive director, Simon Dyer, said in a release.

“That includes a fact-based discussion about the role of the oilsands, which is the fastest-growing source of emissions in Canada. We need a constructive and thoughtful conversation — let’s not shy away from it.”

The report aims to “depolarize the conversation about continued production of oil from the oilsands,” highlighting the success the industry has had in reducing emissions intensity over past decades while also warning of “unprecedented pressures” that lie ahead.

Despite those improvements in carbon intensity, total emissions from the oilsands have more than doubled since 2005 due to increased production and “are projected to keep growing at a similar pace through to 2030,” the report says. That puts the industry on a “collision course” with Canada’s commitment to achieve “deep decarbonization” as part of a global effort to stave off the most devastating effects of climate change.

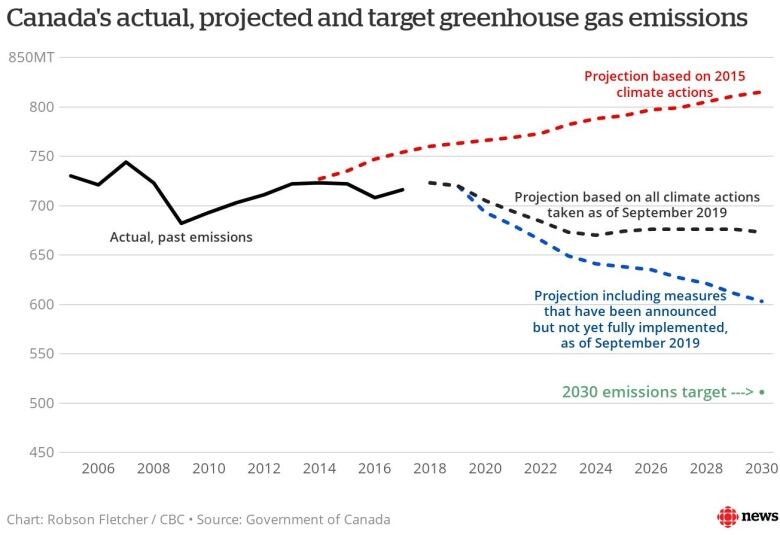

Canada’s annual emissions totalled 716 megatonnes in 2017. Under the Paris Agreement, it has pledged to reduce that amount to 511 megatonnes by 2030, but at its current rate is set to miss that target by nearly 100 megatonnes.

Even more challenging will be Canada’s plan to become carbon-neutral — that is, to have zero net emissions when including carbon offsets — by 2050.

“Business-as-usual no longer applies — significant changes are necessary,” the report reads.

Those changes will be particularly needed in Alberta, which accounts for more than a third of Canada’s total greenhouse gas emissions, the report adds.

It notes the province’s oil and gas sector is “the largest single source of emissions across Canada,” making up 19 per cent of the country’s total greenhouse-gas output in 2017.

“The pathway to make Canada’s oilsands carbon-neutral will not be easy, and will only be more difficult if the discussion is not grounded in fact,” Chris Severson-Baker, the Pembina Institute’s Alberta regional director, said in a release.

“This report answers some of the key questions around oilsands and describes the challenge to go well beyond the incremental gains that have been made to date to reduce total emissions for the sector by 2030 and ultimately achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.”

Several major oil-and-gas companies, including Cenovus, Canadian Natural Resources and MEG Energy have announced long-term plans to make their operations carbon-neutral in the coming decades, although exactly how to achieve that remains an open question.

The Pembina report makes several recommendations it says would help toward that goal, including a return to an industry-wide standard in Alberta’s carbon pricing policy for large emitters.

Effective Jan. 1, the provincial government changed that policy, creating different benchmarks for different facilities, a move the report describes as “a step backward in climate policy.”

“In contrast, the previous provincial regulations were meant to accelerate the adoption of lower-carbon technologies through an industry-wide benchmark that created both a level playing field and a race to the top,” the report reads.

It also recommends improved emissions monitoring, the creation of sector-by-sector emissions targets for 2030 and 2050 made enforceable in five-year increments and the establishment of more “credible and effective” energy regulators at both the provincial and federal levels that have “the capacity to follow through on that enforcement.”

Finally, it calls for a a “robust ecosystem to support innovation, research and development” of new technologies that go “beyond incremental improvements” in reducing oilsands emissions.

Such rapid changes will be necessary not only to meet Canada’s climate commitments, the report says, but also to keep the industry competitive as “global shifts toward lower-intensity energy options are likely to put more carbon-intense crudes — such as the bulk of oilsands products — at risk over the next decade.”

The Pembina Institute is a non-profit organization that produces research, analysis and recommendations on policies related to Canadian energy and climate change.