'We still have title': How a landmark B.C. court case set the stage for Wet'suwet'en protests

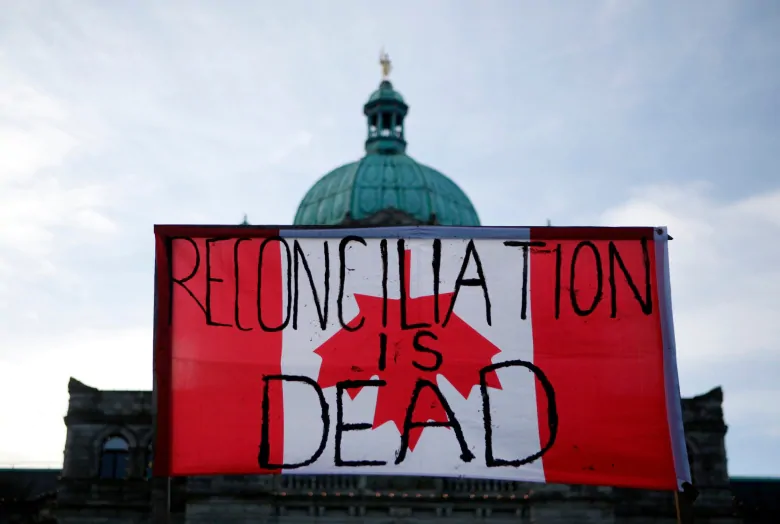

Amid the backdrop of nationwide protests, blockades, and arrests, Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs on the front lines of the fight to stop a pipeline in their traditional territories are pointing to a Supreme Court case from the 1990s that underscores their authority over the land.

The decision in Delgamuukw vs. British Columbia was delivered on Dec. 11, 1997, affirming Aboriginal land title and setting a precedent for how it is understood in Canadian courts.

“The Supreme Court established that Wet’suwet’en had never extinguished title to our territories,” said Molly Wickham, a governance director at the Office of the Wet’suwet’en, on CBC’s The Early Edition. “Within Western law, they have acknowledged that we still have title to our territories — and this is an issue about title.”

Here’s what you need to know about the case — and why it’s pertinent today.

What is the Delgamuukw case?

The Delgamuukw decision stemmed from a 1984 case launched by the leaders of the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en First Nations, who took the provincial government to court to establish jurisdiction over 58,000 square kilometres of land and water in northwest British Columbia.

In 1991, B.C.’s Supreme Court ruled that any rights the First Nations may have had over the land were legally extinguished when British Columbia became part of Canada in 1871.

The First Nations appealed and eventually the case made its way into the Supreme Court of Canada, which found Aboriginal title could not be extinguished, confirmed oral testimony is a legitimate form of evidence and stated Indigenous title rights include not only land, but the right to extract resources from the land.

The case has been widely cited as an influencing factor in future court decisions, including the 2014 Tsilhqot’in decision which further established the existence of Indigenous title to land in British Columbia not covered by treaties.

Why is the case relevant to Wet’suwet’en protests?

Representatives from 20 First Nations — including the elected chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en — signed agreements with Coastal GasLink consenting to the project. The pipeline was subsequently approved by the provincial government.

However, hereditary leaders have not consented to the project which runs through their territories.

In the Delgamuukw case, Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs established that the Indigenous nation had a system of law that predates the days of elected band councils enacted under Canada’s Indian Act.

Under traditional Wet’suwet’en law, hereditary chiefs are responsible for decisions regarding ancestral lands.

In the current dispute, hereditary chiefs say the decision to approve a pipeline in their ancestral lands without consent is an infringement of their Aboriginal title and rights.

Aboriginal title and rights are protected under the constitution.

Are title rights enough to stop a pipeline?

In the Delgamuukw decision, Chief Justice Antonio Lamer outlined that aboriginal title “encompasses the right to exclusive use and occupation of the land.”

However, the decision also notes that Aboriginal rights could justifiably be infringed for the development of agriculture, forestry, mining, and “the general economic development of the interior of British Columbia.” Lamar determined the issue should be examined on a case-by-case basis.

According to a 2014 judgment, infringements can only take place only when there’s adequate consultation, and “the benefit to the public is proportionate to any adverse effect on the Aboriginal interest.”

Kate Gunn, a lawyer with First People’s Law, says the requirements to infringe upon the title rights in favour of a major project like a pipeline would be onerous.

“In the situation where we have a group that’s been in court for years establishing title … I think that the obligations on the Crown [to justify a rights infringement] would be very high,” she said.

No rights infringements were justified through the courts before the Coastal GasLink pipeline was approved.