Canada could be a huge climate change winner when it comes to farmland

Canada will add a huge share of the land that becomes climatically suitable for growing major crops as the world’s temperatures continue to rise, a new study suggests.

The study, published today in the journal PLOS ONE, predicts about 4.2 million square kilometres of Canada that are currently too cold for farming crops like wheat will be warm enough by 2080 if greenhouse gas emissions continue to climb.

“It may become our bread basket for the future. In that regard, it’s good for Canada,” said co-author Krishna Bahadur KC, an adjunct professor of geography at the University of Guelph.

Currently, only a million square kilometres in Canada are warm enough for growing crops like wheat, corn and potatoes, he said.

“It’s a big, huge difference.”

The research suggests that even much of the Northwest Territories and Yukon could get warm enough to grow wheat and potatoes, while corn and soy could be grown farther north than they are now.

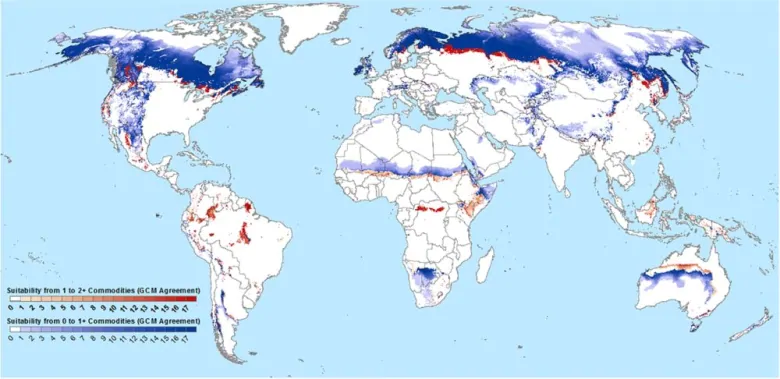

By combining models that predict the future climate with those that show what temperatures are suitable for growing 12 major crops, the researchers showed that around the world, about 15.1 million square kilometres of new land — more than 30 per cent of the land currently being farmed worldwide — could become warm enough for farming corn, sugar, oil palm, cassava, peanuts, cotton, millet, sorghum, rice, potato, wheat and soy.

The new farm land wouldn’t just be found in northern areas like Canada and Russia, but also mountainous areas in other parts of the world, including the tropics.

More farming, more warming

But actually farming all of it could have serious environmental impacts, the study says.

- Huge amounts of greenhouse gas emissions would be released from the soil — about 177 gigatonnes, or 119 times the current annual emissions of the U.S.

- It would destroy important biodiversity hotspots and many of the animals and plants that live there.

- It would degrade the drinking water quality for millions of people.

“We need to proceed to expand agriculture very cautiously,” KC warned, “and also [be] very mindful about possible environmental consequences.”

He said the study aims to highlight those concerns for policy-makers.

The idea for the study came from lead authors Lee Hannah and Patrick Roehrdanz of the U.S.-based environmental organization Conservation International. Experts have long predicted that a warmer climate would make new areas of the world suitable for growing crops. Hannah and Roehrdanz wondered what the impact would be on biodiversity and water quality.

They approached KC and his colleagues at the University of Guelph, who thought they could use models to answer that question. In the process, they realized the release of carbon from agriculture would also be an issue.

In fact, it would be a major consequence of pushing agriculture into Northern Canada, where boreal forests and peatlands store huge amounts of carbon, the study says.

Cutting down the trees and disturbing the peat would release a lot of that stored carbon, as would tilling the soil to grow crops, KC said.

“The magnitude of the potential release indicates that policies directed at constraining development of these areas are vitally important,” the study says.

Climate isn’t the only factor

KC acknowledged the study looked only at climate as a factor when determining where crops could be grown in the future, and didn’t take into account things like soil quality.

Soil scientist David Burton of Dalhousie University, who wasn’t involved in the study, says that could have a big impact on how much of the potential new farmland is actually arable.

“The soils of Southern Canada have taken 10,000 years to develop,” he said. “Rapid change wouldn’t necessarily make soils in Northern Canada suitable for production.”

He said he wholeheartedly agrees people should think about the potential environmental consequences before expanding agriculture into new areas, but he said he thinks policy-makers already do.

Johanna Wandel, an associate professor of geography at the University of Waterloo who edited a book called Farming in a Changing Climate, agrees the soil in much of Canada would likely be unsuitable for growing crops, as it’s too rocky or acidic.

Neither Burton nor Wandel think the expansion of agriculture into new areas will necessarily be the solution to a growing world population and increased demand for food in the near future, especially given the study predicts only 0.2 per cent of existing farmland will become unsuitable for growing major crops due to rising temperatures.

They predict the emphasis will instead be on better technology and productivity on the land we already farm and reducing waste to make harvests go further.

Nonetheless, Wandel said she has great respect for the quality of the modelling in the study.

She said even though the benefits of climate change may be small compared to the negative impacts, “it’s absolutely useful to start talking about some of the opportunities.”