Care home resident Frederick McKay was found dead in the cold. His sister wants answers, and accountability

The death of a Saskatchewan care home resident who wandered away on a cold day in 2017 has left the man’s sister with a lot of questions.

On Boxing Day of that year, 59-year-old Frederick Stephen McKay — Steve to his family — walked out of his rural support home outside Prince Albert.

Cecile Corrigal, McKay’s older sister, still wonders why his body was not found until the next morning, when he was discovered on a portion of grid road less than a kilometre from the care home.

“I want accountability and answers,” Corrigal said. “This could have been prevented. Steve didn’t have to die this way.”

At the time, RCMP said they launched an internal review because their response to the initial call reporting McKay as missing “may not have been sufficient.”

Last week, the RCMP confirmed that review has wrapped. The police force has changed its policy and is now “requiring officers to attend all missing persons complaints in person.”

“As a result of the review, operational guidance was provided to the officers involved,” said Saskatchewan RCMP spokesperson Jessica Cantos, adding she could not confirm at this time how many officers received such guidance.

Corrigal said the RCMP’s findings don’t bring her much reassurance.

“Steve’s life was sad,” she said. “He was alone, and I think about this and it drives me crazy.”

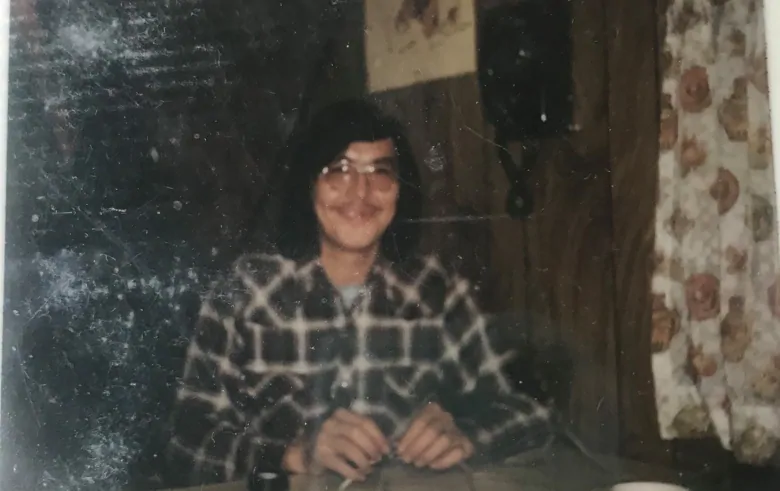

‘He was a great carpenter’

The circumstances that led to McKay living in a care home at the age of 59 date back to his childhood.

Corrigal said she and McKay were Sixties Scoop children, apprehended and placed in separate foster homes.

“Some of them weren’t very good,” Corrigal said. “He got strapped in a barn. Stuff like that, he would tell me.”

McKay graduated from high school and became a journeyman trades worker.

“He was a great carpenter when he was young here,” said Duane Favel, the mayor of Île-à-la-Crosse — a village where McKay lived before being placed by social services in the care home near Prince Albert, about 300 kilometres to the south.

McKay worked at some mines but turned to alcohol and drugs in the 1980s and 1990s, Corrigal said.

“I know that being in foster homes and stuff had a lot to do with the way he was, and why he drank and stuff,” she said. “He had a lot of anger or frustration.”

McKay was also diagnosed with schizophrenia and was prone to running away in the bush, Corrigal said. He lived on and off at her home in Île-à-la-Crosse until 2015, when he harmed himself.

“He’d be really good when he was on medication,” Corrigal said of her brother. “He was a very good person.”

Corrigal said the care home where McKay was placed, located on a farm about 12 kilometres outside of Prince Albert, knew he had to be watched.

Vivian Rasmussen, who runs the small home with her husband, Egon, said the doors have alarms but that McKay managed to bypass them.

Left home around noon

The RCMP detachment in Prince Albert received a call about McKay’s disappearance at about 3:05 p.m. on Dec. 26, 2017, according to the original press release. The Saskatchewan Coroner’s Service concluded he left at around 12 p.m., according to the Ministry of Justice.

It’s not clear from the RCMP when they first went to the farm to investigate. CBC News asked the RCMP when exactly they first arrived.

“Our officers respond to many calls with situations that vary in nature and there are no two calls that require the exact same response,” Cantos said.

“Our officers are expected to respond as the situation dictates. The outcome of our review determined the officer should have attended the area in this particular investigation.”

The RCMP also referred CBC News to the original press release, which only mentioned the time of the call on Dec. 26 and the body’s discovery the next morning, at around 8:30.

Egon Rasmussen said he found the body on the morning of the 27th.

‘I place no blame upon anyone’

According to Cantos, “the [RCMP] investigator was advised by the complainant that they believed the victim may have caught a ride [with] a passerby.”

The Prince Albert detachment asked a northern detachment to check their area, she added.

“They figured, like I had figured, [McKay] must have gotten a ride,” Rasmussen said.

“After I discovered the body [on Dec. 27], it did take a while for them to come,” Rasmussen said of the RCMP.

“I stayed with [the body] for quite some time. I felt obligated,” he said.

“I place no blame upon anyone,” Rasmussen added. “It was very unfortunate and tragic, but I’ll never know what Frederick had in his mind to do.”

The RCMP, in its release, said foul play was not suspected. The cause of death was hypothermia, according to the Ministry of Justice.

McKay’s sister said that she was first contacted by the RCMP about his death on Dec. 27, while she was in hospital in Saskatoon. They provided “very sketchy details as to what really happened,” Corrigal said.

She believes McKay was trying to get home to Île-à-la-Crosse for Christmas.

No charges recommended

In January 2018, the RCMP announced their initial review of the incident determined “our police response may not have been sufficient.” The police force launched an internal review.

According to Cantos, that review wrapped on Aug. 8, 2018. A province-wide policy change requiring “officers to attend all missing persons complaints in person” applies to detachments that receive the missing persons calls, Cantos clarified.

“The change in policy was made to close a gap that was identified as a result of this investigation, not necessarily the expectation of how officers locate a missing person,” Cantos said.

“If there are other areas to be searched in other detachment areas, those officers will assist. The original detachment is responsible to attend the original location of the complaint.”

The RCMP also requested an external investigation into its officers’ actions. The Saskatoon Police Service completed that investigation on Oct. 24, 2018.

“No charges were recommended as a result of the external review,” Cantos said.

At time of McKay’s death, the RCMP committed “to advising the public of the outcome of both the internal review and the external investigation at the appropriate time.”

‘Somebody had to see him’

The temperature ranged from –25 C at 3 p.m. CST on Dec. 26 to as cold as –35 C by the morning of Dec. 27, 2017.

Corrigal said she believes McKay might still be alive today if the RCMP had responded sooner. She’s also “very disappointed” that McKay was able to leave the care home without anyone immediately noticing.

“Somebody had to see him,” Corrigal said. “I mean, [the RCMP and the care home] told us he was close to the house.”

Corrigal said the RCMP brought her the clothes her brother was wearing when he went missing: a winter jacket (“not a thick one”), blue jeans, a T-shirt and Croc shoes. “No thick sweater or nothing,” she said.

McKay left behind a son, who has fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and lives in supported housing, Corrigal said.

“He talks about his dad, like ‘If we thaw him out, he’ll be OK.’

“All I can do is just play along.”