Breaking the silence: Inuvik woman shares story of pain and hope

This story is part of CBC North’s ongoing MMIWG coverage. On Nov. 28, starting at 4 p.m. MT, CBC North will hold a forum in Yellowknife and over Facebook Live, where Indigenous woman will speak to their own experiences and what still needs to be done.

The song Momma, tell him he won’t have to go is Ann Kasook’s personal story of witnessing domestic violence as a child.

Kasook, 68, is a well known Inuvialuit singer/songwriter from the N.W.T.’s Mackenzie Delta region. She’s performed the song countless times at festivals. Over time, thousands have heard her song.

But few saw Kasook’s bruises, or heard from her the story of the violence and abuse in her own marriage which lasted for decades.

“I was always fearful,” said Kasook, who is ready to share her story following the death of her husband Charlie two years ago, himself a well-known musician and community member.

“As much as I went through in life I was able to survive it,” she said. During their 50 year marriage there was love, music and laughter, but also paralyzing fear, threats and abuse, Kasook said.

“It’s time to break the silence.”

Early life and marriage

Kasook lives in Inuvik. With a population of more than 3,000 people, it’s the largest centre in the Northwest Territories Mackenzie Delta region.

Ann Kasook’s earliest memories aren’t of fear but peace.

As a young child she lived at Reindeer Station, a village-like depot for reindeer herders north of Inuvik.

A Norwegian couple, who Kasook called her grandparents, raised her while her biological mother was being treated for tuberculosis in Aklavik.

At the age of five her grandparents brought her to Tuktoyaktuk to meet her mother and her husband.

When her parents were sober there was love and kindness, said Kasook. Both had attended residential school together until they were 18 years old.

“They didn’t know how to be parents,” she said.

Colonization and the intergenerational impacts of residential schooling, along with poverty, overcrowding and limited resources all contribute to the territory’s high rate of violence against women.

“When they drank … my dad would beat up on my mom all the time,” she said. “It became rampant.”

Kasook also experienced abuse in the community. Her family relocated to Inuvik in 1965. Her parents eventually separated

“By then I was really feeling unloved and uncared about,” said Kasook.

She met her future husband in Inuvik. She married him at 16.

“I thought my husband is the only person that will ever love me,” she said.

There was no honeymoon period.

“Then only too [late] realized … I was going to be abused.”

Kasook says she quickly became isolated, only leaving the house when her husband allowed.

The N.W.T. has among the highest rates for police reported intimate partner violence in the country, at nine times the national average for women, according to Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2017. Today, only five of the territory’s 33 communities have shelters. Roughly a third don’t have RCMP officers based in the community year round.

“He would padlock me in the house,” she said. “It was during those years that family violence … it was like who cares,” said Kasook. She said alcohol fuelled her husband’s rage.

Outside the home, her husband was friendly and kind. She believes his dark side was rooted in his experiences attending residential school.

Kasook began drinking as a way to cope.

“I’d drink out of fear,” she said, hoping to black out and forget the violence.

One night Kasook says her husband challenged her to leave him while driving on the highway. He threatened to throw her out of the truck and run her down, she said.

“Instilled with fear all the time,” she said, she developed a stutter, terrified to speak about anything.

Anna Pingo, 51, is Kasook’s eldest daughter.

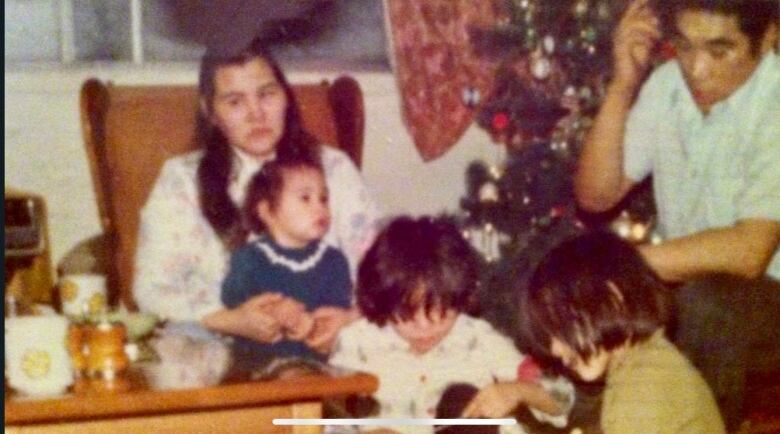

Pingo said the family home was always full of people. Her parents hosted many jam sessions over the years. Her father was a talented guitar player, she said, who was “very kind, very loving.”

“When he wasn’t drinking … he loved us so much. He protected us,” Pingo said.

But when he drank, he was completely different.

“There wasn’t a time where mom didn’t have a black eye or a bruise on her face,” Pingo said about family life in the 70s.

Pingo said the violence slowed down when both her parents quit drinking.

“I vowed that I’ll never ever live that life,” said Pingo. “You don’t have to live the way you grew up,” she said.

She calls her mother resilient.

Breaking free

Kasook broke free from the cycle of violence, but it took decades.

She says she tried to run away only once, unsuccessfully.

One winter night she packed up her two children and fled to another home, only to find the people she hoped would let her in were sleeping.

“We weren’t able to get in the house. So I had to kind of walk — start walking back home.”

Her eldest daughter’s ears froze.

“And I never ever tried to run away [again].”

Kasook said that in 1974 police laid charges, and her husband was sentenced to 6 months probation and ordered not to drink for a year.

The physical violence stopped, but Kasook’s fear didn’t wane.

“The fear was so immense. That went on for a few years after he was sober,” she said.

It was more than a decade before Kasook went for counselling following a trauma related breakdown in 1988.

“I think it’s the small communities [that] really struggle because everybody knows everybody,” she said.

She opted to see a mental health worker in Tuktoyaktuk with her three children, rather than staying in Inuvik close to her husband, or flying further south to Hay River, N.W.T.

“I didn’t even feel safe until I was off the ground,” said Kasook. “That was the first time that I really got some help,” she said.

“I still had fears but I was able to take a stand.”

‘Didn’t have to live like that anymore’

A large plain home in a residential neighbourhood was also a place of healing for Kasook. It’s where the Inuvik Transition House Society supports women and children fleeing violence.

Kasook was never a client, but she worked there as the executive director for nearly 17 years.

“Pretty much almost every story I heard … there’s similarities to what I went through,” said Kasook, who lives not too far from the transition house.

“I was able to realize that I didn’t have to live like that anymore,” she said. “I was able to say ‘No more.’ I realized that I wasn’t alone.”

Dedicated to work at shelter

Kasook often worked overtime and double shifts when the women needed her. While she wasn’t allowed to offer counselling, she always lent her ear.

“In a small community it’s hard to find people you can trust, but if you could find one or two people it makes a difference,” she said.

She stopped working at the shelter in 2017 when her husband became sick with cancer. She took leave from her job to care for him shortly before he died.

Kasook isn’t sure if things have improved for women who are experiencing violence. She worries things may have gotten worse.

“I think people need to really be able to share their stories even though it’s tough,” she said, without judgment from others.

She said it may hurt for her children to hear the full truth about their father.

“They don’t like to hear that their dad was … Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,” she said.

“That’s hard on me because I love my kids and stayed for them.”

When Kasook worked at the shelter, she hung a puzzle on the wall.

The serene landscape image of trees and sky had missing pieces.

“My whole life was a big mess, like a puzzle. And slowly I was putting the pieces back together,” she said.

She told the women she worked with, and herself, it takes time to gather all the pieces.

“I still have some missing pieces,” she said. “But I have enough to form a beautiful picture.”