Fears of election meddling on social media were overblown, say researchers

Now that the election is over and researchers have combed through the data collected, their conclusion is clear: there was more talk about foreign trolls during the campaign than there was evidence of their activities.

Although there were a few confirmed cases of attempts to deceive Canadians online, three large research teams devoted to detecting coordinated influence campaigns on social media report they found little to worry about.

In fact, there were more news reports about malicious activity during the campaign than traces of it.

“We didn’t see high levels of effective disinformation campaigns. We didn’t see evidence of effective bot networks in any of the major platforms. Yet we saw a lot of coverage of these things,” said Derek Ruths, a professor of computer science at McGill University in Montreal.

He monitored social media for foreign meddling during the campaign and, as part of the Digital Democracy Project, scoured the web for signs of disinformation campaigns.

Threat of foreign influence was hyped

“The vast majority of news stories about disinformation overstated the results and represented them as far more conclusive than they were. It was the case everywhere, with all media,” he said.

It’s a view mirrored by the Ryerson Social Media Lab, which also monitored social media during the campaign.

“Fears of foreign and domestic interference were overblown,” Philip Mai, co-director of the Social Media Lab, told CBC News.

A major focus of monitoring efforts during the campaign was Twitter, a platform favoured by politicians, journalists and partisans of all stripes. It’s where a lot of political exchanges take place and it’s an easy target for automated influence campaigns.

“Our preliminary analysis of the [Twitter hashtag] #cdnpoli suggests that only about 1 per cent of accounts that used that hashtag earlier in the election cycle can be classified as likely to be bots,” said Mai.

The word “likely” is key. Any social media analyst will tell you that detecting bonafide automated accounts that exist solely to spread a message far and wide is incredibly difficult.

#TrudeauMustGo and other frenzies

A few times during the campaign, independent researchers found signs that certain conversations on Twitter were being amplified by accounts that appeared to be foreign. For example, the popular hashtag #TrudeauMustGo was tweeted and retweeted in large numbers by users who had the word “MAGA” in their user descriptions.

But this doesn’t mean those users were part of a foreign campaign, Ruths said.

“It’s very hard to prove that those MAGA accounts aren’t Canadian,” he said. “How can you prove who’s Canadian online? What does a Canadian look like on Twitter?”

Few Canadians use Twitter for news. According to the Digital News Report from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, only 11 per cent of Canadians got their news on Twitter in 2019, down slightly from 12 per cent last year.

Twitter’s most avid users tend to be politicians, journalists and highly engaged partisans.

Fenwick McKelvey, an assistant professor at Montreal’s Concordia University who researches social media platforms, said he feels journalists overestimate Twitter’s ability to take the pulse of the voting public.

“Twitter is an elite medium used by journalists and politicians more than everyday Canadians,” McKelvey told CBC. “Twitter is a very specific public. Not a proxy for public opinion.”

In fact, most Canadians — 57 per cent — told a 2018 survey by the Social Media Lab that they have never shared political opinions on any social media platform.

Tweets for elites

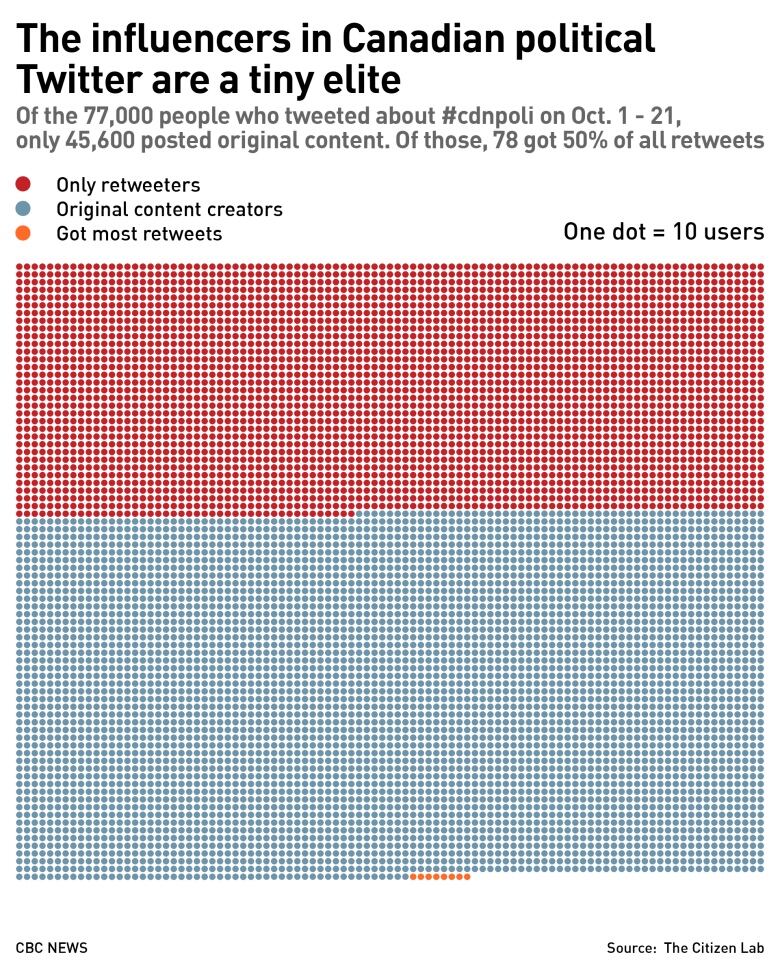

For an idea of just how elitist Twitter can be, take a look at who is driving its political conversations. For some of the major hashtags during the election — like #cdnpoli, #defundCBC, and the recently popular #wexit — just a fraction of users post original content. The rest just retweet.

And the users who get the most retweets, the biggest influencers, represent an even tinier sliver of Twitter users, according to data from the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab, another outfit that monitored disinformation during the campaign.

“What we thought was a horizontal democratic space is dominated by less than two per cent of accounts,” said Gabrielle Lim, a fellow at the Citizen Lab.

“We need to take everything with a grain of salt when looking at Twitter. Doing data analysis is easy, but we’re bad at contextualizing what it means,” Lim said.

So why this focus on Twitter if it’s such a small and unrepresentative medium for Canadians? Because it’s easy to study. Unless a user sets an account to private, everything posted on Twitter is public and fairly easy to access.

On the other hand, more popular social networks like Facebook make it much harder to harvest user content at scale. A lot of misinformation may also be shared in closed channels like private Facebook groups and WhatsApp groups, which are nearly impossible for outsiders to access.

But even taking into account those larger social media audiences, the evidence shows that Canadians are getting their news from a variety of sources, Lim noted.

Although the threat posed by online disinformation to Canadian democracy was overblown in the context of the 2019 campaign, Ruths said he still believes it was important to be alert, just as it’s important to go to the dentist even if no cavities are found.

And he suggests that journalists looking for evidence of bot activity apply the same level of rigour as the people doing the research.

“We saw a lot of well-intentioned reporting,” he said. “But finding suspected accounts is not the same as finding bots. Saying that MAGA accounts don’t look like Canadians’ doesn’t mean they’re not.”