Considering John Ford’s ‘Apology Western’ Sergeant Rutledge

John Ford, who was once accurately described as a “tough, two-fisted, hard-drinking Irish sonofabitch,” has justifiably gone down as one of the greatest directors ever. On the surface, his films seem simple and uncomplicated, very much in the studio style of directors of the period from the 1930s though the mid-’60s. But on closer examination, Ford’s authorship displays a nuanced approach, complexity, emotional depth, and penetrating characterization that many films made by his peers sorely lacked.

During his very long career as a film director, starting in the silent era in 1917 until “Seven Women” (his exquisite final film in 1965), he made more than his fair share of classics which still stand the test of time: “The Informer,” “The Grapes of Wrath,” “My Darling Clementine,” “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” and “How Green Was My Valley.”

Though he made films in every genre, from dramas to historical epics, romances and even comedies, Ford has been justifiably associated with the Western and is considered one of the most influential directors in that genre. He directed so many that Ford once said of himself, “My name is John Ford. I make Westerns.”

However, despite the fact that Ford considered himself a political progressive (though he was close friends with actors he worked with that were right wing reactionaries, like John Wayne, James Stewart, and the even more right wing Ward Bond), he was often labeled a conservative.

Ford’s films were not above dealing in negative racial stereotypes. He regularly portrayed Native Americans in most of his Western films as bloodthirsty savages. On top of that, in the early 1930s, Ford also made several films with long-lambasted black character actor Stepin Fetchit, like “Judge Priest” and “Steamboat Round the Bend,” in which he, in all his films, played degrading and embarrassing roles as a slow-witted, lazy buffoon.

In fact, Ford started out his film career as an actor and stuntman in silent movies including, according to Ford himself, D.W. Griffith’s notorious “The Birth of Nation.” He can be seen as one of the Klansmen, who in the dramatic climax rescue the white people under threat by savage “renegade” Black Union soldiers.

However, by the mid-’50s, when Ford was nearing the twilight of his long career, the director seemed to have mellowed with age, discovering and exploring a more humanist side to himself. Perhaps it was the changing times, especially after the emergence of the modern Civil Rights Movement era. Maybe he saw his own mortality down the road, or simply changed his opinions to become more open-minded and accepting.

The result was a few films in which he seemed to be, in a way, apologizing for the wrongs he committed in terms of his distorted portrayals of people of color in his previous films. But Ford was also challenging the misty eyed, romanticized images of the west that he portrayed in many of his films about strong willed, determined, loner men battling a hostile environment.

There was the myth-breaking 1962 Western “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” in which Ford reexamines that whole mythos of the west he helped create. In 1964, there was his penultimate work, a nearly three-hour-long 70MM Super Panavision roadshow western epic for Warner Bros. “Cheyenne Autumn” told the true story of the Trail of Tears, and focused on the Cheyenne tribe who travelled by foot across 1,500 miles back to their ancestral hunting grounds. They defied US Army troops ordered to send them back by force if necessary.

Though the film is an ambitious attempt to deal with how this country has historically and unjustly dealt with Native Americans (and there are several impressive scenes in the film), “Cheyenne Autumn” suffers seriously by Ford’s ponderous direction and a wobbly meandering script. His stilted “wooden Indian” characters, a lot of the time, stand like stoic statues, with the major speaking parts played by either Latino or Italian-American actors such as Richard Montalban, Dolores Del Rio, and Sal Mineo. There’s also one too many boring side stories involving white characters.

Four years earlier, in 1960, Ford made a more modest and more successful Western that has been overlooked and forgotten, “Sergeant Rutledge,” a film that remains pretty remarkable and advanced for its period. It tells of a black U.S. Calvary sergeant of a regiment of black troops, played by Woody Strode.

In the film, which is mainly told in a series of flashbacks during a court martial, Strode’s First Sargent Braxton Rutledge of the all-black 9th U.S. Army Calvary (which was originally established in 1866 as one of the U.S, Army’s first all black segregated units stationed in the west and southwestern Texas) has found himself in a dire situation, accused of murdering his white commanding officer and for the rape and strangulation of his daughter.

Though the shooting of the officer was in self-defense after he shot and wounded Rutledge, Rutledge proclaims his innocence of the murder of the white woman. When hiding at a abandoned railroad station that is attacked by the Apaches, Rutledge saves the life of Constance Towers, the sweetheart of Lt Cantrell (Jeffery Hunter). Cantrell arrests Rutledge after coming back to the station to save Towers and eventually defends him at his court martial. After he is arrested by Hunter, Rutledge knows that that he has no chance of getting a fair trial, or, as he bluntly says to his follow black troopers, “I walked into something none of us can fight … White woman business!” A truly remarkable line of dialogue in a film released just five years after Emmett Till.

Rutledge escapes in the hopes of making it north to freedom. But when he discovers a group of Apaches are lying in wait ready to ambush the 9th along with Hunter and Towers, he goes back to warn them of the attack and takes command of his troops and tries to save the life of one of his men seriously wounded on a runaway house. Though Rutledge is commended for his heroic deeds, he returns to face trial.

Naturally, he is found innocent when the real culprit of the crimes is revealed and he confesses on the stand in the film’s only real misstep in a scene so overwrought, overacted, and tonally off that it seems to have come out of some Victorian melodrama. His innocence proven and honor restored, Rutledge returns to the 9th with the final shot of him leading his troops through Monument Valley as an off-screen chorus sings “The Buffalo Solder” on the soundtrack.

Ford, who was usually straightforward when it came to the visual aspects of his films, shows some real cinematic and dramatic creativity. The narrative structure is told mainly in a series of flashbacks in which information is revealed in bits, leaving us guessing as to what really happened. But Ford also effectively takes advantage of Strode’s muscular, broad-shouldered, overpowering presence, shooting him often from a low angle to let him dominate the frame and the audience.

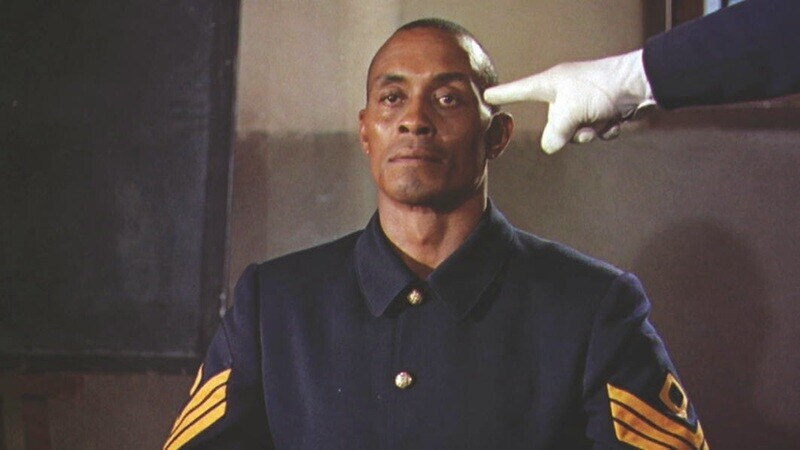

When Rutledge is first on the stand, Ford cuts to a dramatic striking shot of the prosecutor’s white gloved hand pointing an accusing finger at Rutledge. The glove practically exaggerates the whiteness of the prosecutor, commenting on the injustice that innocent black men have faced on trail for crimes they did not commit. It’s further exacerbated by the prosecutor’s constant references to Rutledge being “A Negro,” or with the white gloved hand his insistent pointing at him calling “That man,” coded words for “that BLACK man,” or even worse. Needless to say, the crime has set the townspeople aflame with hatred, as a lynch mob in the back of the courtroom itches to take matters into their hands.

In addition, during the trial sequences, Ford frequently leaves the actors in silhouette during the more emotional moments of their testimony. When Rutledge is on the stand, Strode is lit alone in the witness chair, surrounded by darkness, abandoned and helpless as many Black men on trial have felt.

Throughout the film there are little telling touches about the life of Black men during that period. In one touching scene, the oldest member of the troop, the gray-bearded Sgt. Skidmore (played by the wonderful character actor Juano Hernandez) takes the stand and is asked how old he is. He replies he has no idea because he was “slave born” and tells the judges memories of things he remembers as a young slave boy. The judges gasp when they realize that Skidmore must be at least 70 years old, older than all of them, with most of that life in bondage.

And Rutledge knows the pain and horrors of slavery. Though his past is never revealed, he is, as were almost all Black men who served in the Army during that second half of the 19th century, an ex-slave who had run away to join the Union Army during the Civil War and continued serving in the Army.

One telling scene is when Rutledge mockingly tells Cantrell, “You know what they say about us sir, we heal fast,” repeating an often used racist expression that slave owners said to justify slavery. And in a later scene when talking with his comrades about the obstacles they still face, even though they proudly serve their country, Rutledge says to them, “It was Mr. Lincoln to say we were free, but that ain’t so. Not yet. Maybe one day, but not yet!”

Ford even plays on the image of the sexual savage imagery of Black men which Griffith exploited in “Birth of a Nation” with his Black characters Gus, “a renegade Negro” who attempts to rape a young white girl, and Silas Lynch, who dreams of being the ruler of an all Black nation, and wraps his arms around the white frail Lillian Gish proclaiming that he will make her his queen. The idea that a brute Black man would defile the pure white innocence of white woman literally made audiences panic. The close-up shot of Rutledge’s gigantic Black hand over Towers’ mouth to keep her from screaming and warning Apaches must have sent similar feeling of panic.

Later, when Rutledge is in a small cramped room with Towers, he takes off his shirt to tend to his wound. He reveals his chiseled body, and there’s an underlining sexual tension that Ford subtly handles. But the sequence is sexually charged in a way that amplifies the tension between a white woman and a bare-chested Black man. No doubt the film was banned in the south (and other parts of the country) by some theater owners as being too explicit and offensive for audiences.

Even the final happy ending has a bitter edge: Rutledge never thanks Cantrell for being his defense lawyer and goes straight back to leading his Buffalo Soldiers out for another tour of duty. Though Rutledge and his men march by and smile when they see Hunter and Towers kissing, there’s no sentimentality or hopeful message. The film suggests that though a Black man was found innocent, racial tensions will always exist; so what is the use of pretending that all is suddenly well? The same thing will happen again to another Black man and he probably won’t be as lucky as Rutledge.

Strode is perfectly cast and gives a powerful performance in one of the very few lead roles he ever played. However, it’s interesting to note how Strode was treated in other Ford films. As Pompey in “Liberty Valance” he is John Wayne’s hired hand and eventual savior, though his part does not stray far from the submissive stereotypical Black lackey role. In fact, James Stewart complained to Ford that he felt Strode’s outfit in the film was too stereotyped. In “Two Rode Together,” Strode plays a small role as a Native-American warrior and, in “Seven Women,” which is set in 1935 China, Strode plays a Mongolian warlord who terrorizes the Christian missionary women main characters being held captive. The character of Rutledge was in many ways an exception for Strode and Ford, and one that would not be repeated.

“Sergeant Rutledge” was also one the first times in which a Black man was seen as a cowboy or an Army soldier, and not as a slave, a cook, or a Pullman porter in a Hollywood feature Western. There were a few Black Westerns made during the “race films” era of the 1940s, such as “The Bronze Buckaroo” and “Harlem Rides the Range,” but never before had a Black man been the lead character in a Hollywood studio Western film.

Warner Bros. obviously thought that the audience wouldn’t be able to handle it. The studio even tried to trick audiences into thinking that the film was about the white characters. In the film’s trailer, Strode is given third billing. And in the film’s opening credits, he’s not given a single credit like Hunter and Powers but is listed in the credits at the top among other actors grouped together. Even worse is the poster for the film on which Strode appears, though his name is listed fourth and in small letters.

Not surprisingly and given the subject matter as well as the era in which it was made and released, “Sergeant Rutledge” was not a box office success either though it did get genuinely respectful reviews. However, it must have made a real impact on Ford himself, since, in the early 1970s, he planned to come out of retirement with a new film about the life of the first Black graduate of West Point, Henry Flipper. But with his ill health and advancing age, the project was dropped and Ford passed away in 1974.

“Sergeant Rutledge” needs to be rediscovered and appreciated for being a remarkable film from its time, and during a point in Ford’s career where he was exploring new themes and ideas. Though it has many Fordian themes and visual trademarks (Monument Valley makes a majestic appearance), it also marks a different Ford film, one which not only looks at the past but examines the false narratives that have hidden the truth.