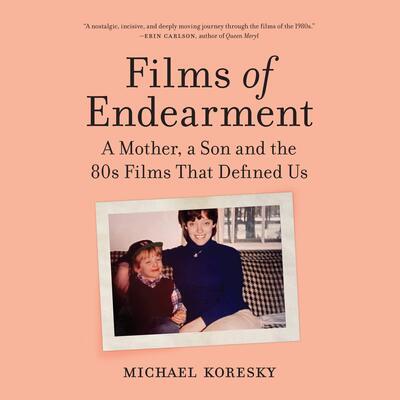

Book Excerpt: Films of Endearment by Michael Koresky

We are proud to present an excerpt from Michael Koresky’s moving new book, Films of Endearment, now available. Get a copy today by clicking here; read our interview with Koresky here.

Synopsis:

A poignant memoir of family, grief and resilience about a young man, his dynamic mother and the ’80s movies they shared together.

Michael Koresky’s most formative memories were simple ones. A movie rental. A mug of tea. And a few shared hours with his mother. Years later and now a successful film critic, Koresky set out on a journey with his mother to discover more about their shared cinematic past. They rewatched ten films that she first introduced to him as a child, one from every year of the ’80s, each featuring women leads.

Together, films as divergent as 9 to 5, Terms of Endearment, The Color Purple and Aliens form the story of an era that Koresky argues should rightly be called “The Decade of the Actress.”

Films of Endearment is a reappraisal of the most important and popular female-driven films of that time, a profound meditation on loss and resilience, and a celebration of the special bond between mothers and their sons.

Leslie Stone was born in 1948, nearly thirty years before me. She grew up in Boston in the 1950s. Regularly taken to the cinema by her mother, Bertha, she was swept away by Audrey Hepburn in romantic comedies like Roman Holiday and Sabrina, by Leslie Caron in musicals like Lili and Gigi, and by Elizabeth Taylor in adult dramas like Giant and Suddenly Last Summer. Regardless of the much-theorized social and political repression of the era, reflected today in clichéd images of subservient women in strictly domestic, homemaking spaces, representations of female indomitability were nevertheless imprinted upon her. For Leslie, it was actresses such as Hepburn, Caron, and Taylor, as well as Natalie Wood, Debbie Reynolds, Jean Simmons, Joanne Woodward, and Deborah Kerr, who helped define her sense of self. Moreover, movies were an escape from her volatile and itinerant childhood. Despite the trauma of her emotionally erratic home life, she and my grandmother, also a lifelong film fanatic, would bond at the movies. Sometimes Bertha would even let Leslie skip school so she could accompany her to one of the many Boston-area theaters that today light up my mother’s memory with intense longing.

When my mother was a teenager, she enrolled in an art appreciation course that was part of her regular curriculum. Though she never went on to a career in the arts, the class proved to be deeply influential. Lessons on Matisse and Picasso, on French impressionism, pointillism, and modern abstract expressionism, on 20th-century modernist architects like Frank Lloyd Wright, were interspersed with presentations of films. She would tell me about this class when I was a kid, but only later did I realize how remarkable this was in the mid-1960s, years before film studies courses were in vogue even in American universities.

This class has long been a source of fascination for me, an apocryphal story of artistic discovery. I have often asked her about the nearly mythic figure of her middle-aged teacher from Newton High, so ahead of the curve, imparting wisdom and knowledge about The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Citizen Kane at a time when few movie-lovers, let alone art instructors, would even have had the basic language to discuss them. “There was no such thing as video yet, so he must have been shown the movies on 16mm projection,” I marvel to my mother one night.

“Mr. Schmidt,” she recalls his name, though quizzically. A couple minutes later, eureka: “No, it was Mr. Schultz!” We went flipping through her high school yearbook—the one I desecrated as a child by scrawling the word MOM across my mother’s senior class photo—looking for a picture of Mr. Schultz, but to no avail. He only exists in her memory now. Aptly for something recalled with such haziness, the course was taught in the basement; she remembers walking through cement corridors with exposed pipes. Nevertheless, it opened up a new world for her—and, decades later, for me.

Without even knowing she was doing it, Leslie would pass on to me a seriousness of intent, a tacit instruction to look at a film as more than just a couple hours of story-driven entertainment. One forgets how resistant many people are to this idea in our culture, in which a movie is most often talked about

in terms of box-office performance, like a gleaming product off the assembly line destined to either “work” or not, like a toaster. Under her influence, I remember trying to look deeper into movies at an early age. I remember chastising other kids in kindergarten when they called Walt Disney’s Fantasia “boring” because it “had no story.” I’m sure I was wildly irritating. I remember when she sat me down to watch 2001: A Space Odyssey on VHS at age seven it was with the understanding that I would be witnessing art. Despite what I would now call an unreasonably small screen on which to watch Stanley Kubrick’s mind- and eye-expanding masterpiece, I was swept away and deeply moved. When the film ended, when the Star Child’s expectant, impassive face filled up the screen, waiting to return to Earth for some unknown but clearly important reason, my eyes welled up with tears. Tears at the sheer power of art to move something inside you, something you can’t touch or explain.

Movies themselves thus had a maternal air cast over them. This could not, of course, produce a full alchemy in which the masculinist film historical narratives we all grew up with—in which men became heroes of mythic proportion and women were supportive at best, subservient and abused at worst—were somehow reversed. But for this gay kid growing up in suburban Massachusetts, it allowed movies to be a wondrous, warm, feminine space in which I could glean an emotional understanding of the world. Throughout my childhood, before I struck out on my own as a rabid cinephile, I wanted to see everything she had seen. I would open the hardcover Oscar book she got me as a Hanukkah present at age eight, go page by page and quiz her on all the classic films listed—not just obvious ones like Casablanca and An American in Paris, but movies with more exotic, enticing titles: Leave Her to Heaven, The Valley of Decision, Johnny Belinda, The Snake Pit, Splendor in the Grass, La Dolce Vita, Love with the Proper Stranger, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, Days of Heaven. Perhaps one day I would actually see these movies, but for now it was enough that she had. An entire history was slowly coming into focus.

The eighties, then, were for me an era of absorption, taking it all in—to borrow a phrase from the critic Pauline Kael—in a steady, mostly unthinking stream. Later I would become too opinionated about movies to be quite so open-minded. Even in my teen years, even on glorious summer days, when watching movies all alone, up in my room, lonely and hermitized with my weekly stack of videotapes from local libraries, I was often seeing films through my mother’s eyes, implicitly understanding them and their situations as projections of her own thoughts, wishes, and fears. Paired with the inherent loneliness and solitude of cinephilia, of the need to retreat into a safe space untouched by the masculine cruelties of daily life, I now see it as the gradual creation of a refracted queer consciousness.

As she approached middle age, and I was graduating college in New York, things changed drastically for her and all of us with my father’s diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s. The painful, decade-long process, leading to his death in 2011, changed us all immeasurably; acting as his primary caretaker, she struggled with his sickness more than any of us. Throughout all this, my mother and I never stopped watching and talking about movies: old and new, good and bad, inspiring and depressing. Only later did I realize how much we needed movies, and though she never said it to me, what a persistent source of comfort, what an intellectual and emotional escape, they remained for her. At least through movies we could momentarily forget what was going on and redirect our focus to ideas, characters, images, costumes, performances—other people’s narratives. Movies speak to our anxieties and despair and say the things we don’t. They keep our secrets.

One chilly October night in 2018, while I was visiting home, the two of us were in the dining room, eating takeout from the preferred Cantonese-American restaurant of my youth, the amusingly, dubiously named Hong & Kong. Unhealthy fried delights scattered the table. She was nibbling, I was devouring; I used chopsticks, my mother a fork. A merlot was uncorked. There have been few simpler pleasures in life than opening a bottle of wine—a single glass for her, more than that for me—and talking at the dining room table with her as evening gives way to night. These days, alone together in that house, as the shadows outside grow long, it can feel like we’re the only ones in the world.

Dinner conversation turned, as it always does, to movies. Leslie is always thrilled to animatedly express disgust at the latest aging actress who has noticeably had “work done,” or to sing the praises of some Jennifer Aniston rom-com she’s watched for the seventh time—but she’s also apt to rummage through her cinematic past with meditative rigor. We started discussing films she grew up with, talking about the differences between distinct movie eras. Out of curiosity, I asked her which decade stands out as her favorite.

“The eighties,” she responded, barely missing a beat, before taking a sip of wine.

As I helped clear the table, putting the leftover egg rolls and spare ribs in Tupperware, I kept obsessing over what felt, strangely, like a revelation: that my movie decade was also somehow her movie decade. I wanted to do the research into my mother’s past and present, to seek out things I didn’t know or learn more about the things I only thought I knew.

I asked myself, What do I really understand of her life before she was a mother? About her various jobs, both before and after I was born? About the curtailed singing career of her youth? How does she define her political selfhood, and her aspirations and dreams, then and now? I really didn’t know very much even about her current life as a widow, living alone with that sweet-faced little cat in that quiet suburban house that once burst with family life.

Conversely, what have I allowed her to really understand about me, about my identity as a gay man now and my struggles as a queer kid growing up in the years before homosexuality was much talked about, if at all, in the home or the culture at large?

There are things we’ve just never spoken about. However, taking a seat and just asking my mother about her life felt like anathema to me. It’s not my way. Movies, in effect, started these conversations, and movies would have to finish them. After all, they provided us with a kind of private language.

Sitting down to make a list of the most important female-driven films of the eighties, I realized that my mother had introduced me to practically all of them, brought into the house on VHS tapes, boxed treasures presented to me with anticipation, intrigue, or foreknowledge. Yes, throughout my childhood, my mother was impressing upon me the importance and centrality of Beethoven and Monet, John Steinbeck and Aretha Franklin, but also Sissy Spacek and Jessica Lange, and why not? For families, movies are totems, passed down through generations, and like relationships, how we perceive films deepens with time.

The more I thought about these female actors, and the films they were in, the more I realized that each could unlock a new facet of my mother’s life left too long uninvestigated by me. If I watched some of these movies again with her, we might open up a new dialogue. I’d also have an excuse to visit more often. I wasn’t moving back home—heaven forbid—but I would be coming home more regularly than I had in years, which would have the effect of making me feel like I was journeying back in time.

Thus, over the course of sixteen months, we would rewatch and discuss ten female-driven films from the eighties that were either influential on me or which I knew spoke to her on a deep level. There would be one selection from each year, better to give the proper span of a complete decade. They’d vary in genre and tone, from comedy to tragedy, from low-budget to blockbuster; each reveals an aspect of the era’s social mores and industrial realities, as well as new things about my mother’s life that I never knew. Some are favorites we’ve shared many times, others she forgot about after first introducing me to them, and still others are films she has willfully avoided since last seeing them in the eighties. As part of the mission—not quite a game, but I like to give myself rules and challenges in my writing—I wouldn’t tell her ahead of time each new movie I selected, perhaps all the better to let each marinate as its own specific experience with its own particular emotional contours. The project took on a life of its own, naturally weaving its way into the fabrics of rituals and events: holidays and celebrations, health concerns and worldwide crises.

By exploring and discovering truths about my mother’s perspective and interior life I may never have known or seen, I was creating a personal history via a pop cultural one. After all, we often wrestle with movies and their meaning more frequently and willingly than we do our own lives. I once watched these films through this forty-something woman’s eyes; what does it mean, in this radically shifted world, to watch them through a seventy-something woman’s eyes? And what do I acknowledge about myself now, as a married gay man who has entered his early forties, when I revisit these films through this double lens?

And if I do not have children of my own, will these movies as I know them, as we know them, get lost to time? For me, the story of film is the story of a mother and a son, and both the fragile and unbreakable bonds that unite us.

Excerpted from: FILMS OF ENDEARMENT: A Mother, a Son and the 80s Films That Defined Us (Hanover Square Press) by Michael Koresky. © 2021 by Michael Koresky, used with permission from HarperCollins/Hanover Square Press. To order your copy, click here.