How a pandemic struck a British PM and changed the world. No, not this one

Britain’s prime minister lay sequestered in a room for days, struggling to survive the deadliest pandemic of the century, while scant details trickled out to the public.

Boris Johnson in 2020? No, David Lloyd George in 1918.

The Spanish flu left a staggering trail of consequences on politics around the world, with Lloyd George one of numerous world leaders afflicted.

It killed the South African prime minister and the prince of Sweden. It sickened the Spanish king, the German kaiser and possibly the American president. It crippled First World War armies.

The long-term effects echoed even further: It spurred calls for universal health care and shaped the history of India, South Africa, the Soviet Union, Germany and beyond.

“You can’t lose that many people in the world — you can’t lose between 2.5 and five per cent of the population — without it impacting human activity in every domain, including politics,” British science writer Laura Spinney, author of the Spanish flu history Pale Rider, said in an interview.

She suspects the current smaller-scale pandemic will also shape major global events, and accelerate geopolitical developments already in motion.

WATCH | Boris Johnson admitted to ICU after COVID-19 symptoms worsen

Her own instinct is that future historians will see this coronavirus pandemic as a milestone moment in the great-power rivalry between China and the U.S.

Their already frosty relationship now includes bitterness over the pandemic, finger-pointing, expelled U.S. journalists and new trade tensions as countries fight over China’s supply of life-saving medical products.

Lloyd George survives

Britain was on the cusp of victory in the First World War, and authorities suppressed the morale-sapping news that Britain’s leader was gravely ill.

In her book Pandemic 1918, Catharine Arnold describes how traffic was diverted from a Manchester town square, away from the room where Lloyd George fought for his life.

Newspapers contained scraps of information: a brief two-sentence story in the New York Times announced Lloyd George was ill; two days later, an equally brief story said he was better; then a day later that he’d suffered a relapse.

Lloyd George survived the Spanish flu and went on to live another three decades.

The British empire, meanwhile, was collapsing.

India

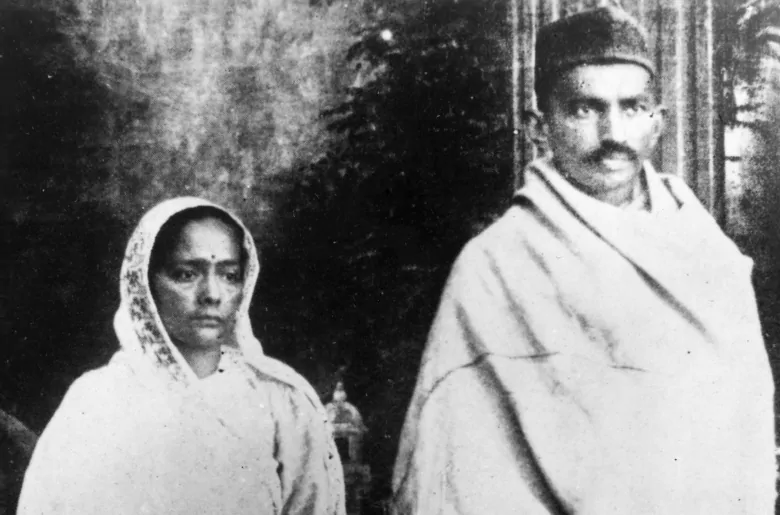

In India, a middle-aged Mahatma Gandhi had just moved back home from South Africa to pursue the independence cause.

A staggering number of Indians were killed by the flu — up to 17 million, making it the hardest-hit country.

The illness raged through Gandhi’s ashram and he fell ill. His daughter-in-law and grandson died, and he told loved ones he was also resigned to death.

Gandhi survived. His country, meanwhile, fumed at British-led authorities, seen as indifferent to Indian suffering and too incompetent to offer basic medical care.

“Indian nationalists blamed the [British] Raj for the pandemic — one nationalist newspaper ran the comment ‘The Raj are doing nothing and we are dying like dogs!'” Arnold told CBC News.

Gandhi’s popularity surged.

Until that point, Spinney said, Gandhi’s movement had elite appeal but lacked grassroots backing.

“Then the pandemic happens,” she said.

“In 1921 he called a general strike, and had millions of supporters — which he’d never had before.”

He became leader of the Indian National Congress in 1920. By the next year, he’d led a mass movement that included burning foreign clothes. British troops had fired at civilian crowds, and when one crowd burned a police station, Gandhi declared a fast.

In 1921, he was a globally recognized figure, on the front page of the New York Times, heralded for his “sway over Indians.”

While independence wasn’t declared until a few years later, and not achieved until 1947, Spinney says 1918 shaped India’s independence cause as it spurred a mass movement and established Gandhi as the undisputed leader.

South Africa

Meanwhile, the flu was also aggravating racial tensions in the country Gandhi had recently left: South Africa.

Influenza ripped through the country and killed about 300,000 South Africans in six weeks. It killed Louis Botha, the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa, forerunner to the modern state.

Medical historian Howard Phillips of the University of Cape Town describes corpses lying in pastures where animals wandered unherded.

And he writes that, as is often the case in a life-threatening epidemic, blame-mongering soon began across the fault lines of a divided society.

“Some whites blamed Africans for recklessly spreading the disease.… There were even calls for them to be barred from the trains to curb this,” Phillips writes in his book Epidemics: The Story of South Africa’s Five Most Lethal Human Diseases.

Racial animus was already rampant. But Spinney said that in the aftermath of the pandemic, pivotal new segregation laws were enacted that discriminated against blacks.

“[The flu] was kind of like the stimulus that pushed those existing tensions over the edge,” she said.

“That’s kind of the beginning of apartheid. And it’s really tragic.”

The Soviet Union

Her book also describes how the flu struck Russia’s new Bolshevik leadership.

Yakov Sverdlov had been Vladimir Lenin’s right-hand man since Lenin survived an assassination attempt in early 1918. He was also officially Russia’s leader, as chairman of the Central Executive Committee.

Sverlov caught the flu and died within a week. In Spinney’s book, revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky described getting telephoned by an anguished Lenin saying, “He’s gone. He’s gone,” followed by dead silence for the rest of the call.

“Sverdlov replacements came and went — all of them lacking his formidable energy, all of them unequal to the enormous task of building a communist state from scratch,” Spinney writes.

“[That’s] until in 1922, [when] Joseph Stalin stepped into the role.”

Europe, North America

Meanwhile, western European nations emerged bitterly divided from the war. Several were in a vengeful mood against the country they viewed as the instigator: Germany.

At the 1919 Paris conference, the role of peacemaker fell to American President Woodrow Wilson.

He pressed the hawks for leniency and threatened to leave the conference.

At one point a furious French leader Georges Clemenceau called Wilson pro-German and left the room, John Barry writes in his book The Great Influenza.

There’s debate over what happened next to Wilson. Barry is adamant that he was struck by the Spanish flu: a young aide, Donald Frary, got sick the same day as Wilson and died four days later.

Another aide describes Wilson being seized with violent paroxysms of coughing, and a fever that hit 39.4 C.

Wilson lay in bed for several days, unable to move.

A feeble president eventually returned to the table, and shocked onlookers, including his own delegation — he suddenly caved to the hardliners.

A stunned future president Herbert Hoover was at that conference and described Wilson as a changed man.

Hoover was incredulous at the one-sided deal Wilson accepted, and warned it would tear Europe apart.

Barry lists the conditions forced upon Germany: financial reparations, an apology, demilitarization of the Rhineland, ceded control of coal fields, parts of the country given to France and Poland, the eradication of Germany’s air force, its army limited in size.

“No one can know what would have happened [had Wilson remained healthy],” writes Barry, professor at the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine in New Orleans.

“One can only know what did happen. Influenza did visit the peace conference. Influenza did strike Wilson [and affected him].

“Historians with virtual unanimity agree that the harshness toward Germany of the Paris peace treaty helped create the economic hardship, nationalistic reaction and political chaos that fostered the rise of Adolf Hitler.”