CBC News poll: Why the economic crisis could speed up transition to renewable energy

Editor’s note: CBC News commissioned this public opinion research before concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic mounted. About half of the total survey of 1,200 respondents was conducted before stock markets and oil prices plunged (March 2-8). The other half of the interviews took place after this economic shock (March 9-18). Our analysis found no real difference in public opinion about energy transition between the two periods. Growing concerns about the pandemic continue to shape public attitudes.

As with all polls, this one is a snapshot in time. CBC News — and the public opinion experts consulted on this survey research — believe the data offers some valuable insights into Albertans’ attitudes about the economy and politics just at the moment when COVID-19 changed everything.

This is the fifth article to come out of this research. Read the previous articles here:

It was sombre. It was serious.

Premier Jason Kenney’s televised address to Albertans last week delivered a sobering reckoning of “perhaps the greatest challenge of our generation” facing the Prairie province.

First — and most pressing — the health crisis sparked by the coronavirus pandemic could, in a probable scenario, see as many as 800,000 infections, and between 400 and 3,100 deaths in Alberta.

The economic ramifications of the infection are profound, with the most recent forecast estimating that one in four Albertans will lose their jobs and the crisis will “permanently reshape” the province’s economy. As Kenney has said, it could be an economic disaster equivalent to or worse than the Great Depression.

The International Monetary Fund’s most recent estimates forecast massive global decline, and a terrible situation for energy prices — Alberta’s bedrock industry.

The future of the industry is unclear.

A CBC News poll, taken just before the economic implications of the coronavirus were becoming clear, suggests 79 per cent of Albertans already thought that the province should transition toward renewable energy. More than nine in 10 Albertans also think the province should do more to encourage the development of the technology sector.

And 51 per cent think that the province should transition away from oil and gas.

While support for transitioning away from oil and gas is highest in Edmonton (58 per cent), it has similar levels of support in Calgary (55 per cent). Outside the province’s two major cities, only about a third of Albertans (37 per cent) support moving away from oil and gas.

There is general agreement that Alberta needs more renewables. Albertans are divided on whether or not to wind down the oil and gas industry.

The question is, how do you fix and reshape Alberta’s energy-dependent economy while looking after people caught up in the change?

Albertans have debated diversification for years, but there’s an argument to be made that the coronavirus crisis offers an opportunity to speed up diversifying the economy and transitioning to more renewable energy sources.

A blend of traditional and renewable energy

Calgary-based pollster Janet Brown has detected an increasing desire amongst Albertans to diversify Alberta’s oil and gas-dependent economy over the past couple of years.

“Albertans don’t necessarily want to abandon the oil and gas industry, but that doesn’t mean they don’t want to see the economy transition away from the oil and gas industry,” said Brown, who conducted the research for CBC News.

“It’s about … keeping the industries that we rely on strong, and diversifying so that in the future we’re not so reliant on any single industry,” she added.

And that’s key: To keep oil and gas viable in the short term, while beginning a green transition.

Even before COVID-19, Kenney acknowledged that Alberta “will see a gradual shift from hydrocarbon-based energy to other forms of energy.”

That said, in recent weeks, Kenney has pressured the federal government to help the province’s beleaguered energy industry, recently suggesting that he anticipates significant federal support for the sector.

That assistance has been expected for some time but hasn’t yet arrived.

The renewable energy industry, for its part, is pressuring Ottawa to stimulate the pandemic ravaged economy by investing in wind energy, hydro power and electric vehicles.

At the same time, hundreds of academics — including prominent Alberta scholars — recently called on the federal Liberal government to reject bailing out Canada’s energy industry, and instead accelerate a green transition.

They stressed that “growing demand for climate-friendly energy sources further threatens the viability of high cost, carbon-intensive oilsands production.”

In an email statement to CBC News, Kavi Bal, the senior press secretary with Alberta’s Ministry of Energy, said, “We’ve always acknowledged the gradual energy transition, but by all accounts, oil and gas will be needed for decades to come — not just in Alberta, but globally.”

In the same statement, Bal described the academics’ open-letter as “rich,” noting that the “Alberta-based signatories benefit from generous salaries, in part, because of the very oil and gas that they denounce.”

For decades, Albertans have talked about economic diversification and energy transition, but the economic crisis brought on by the pandemic has intensified the argument.

As Rahm Emmanuel, former U.S. president Barack Obama’s first chief of staff, quipped to the Wall Street Journal, “you never want a serious crisis to go to waste.”

Don’t waste a good crisis

Years ago, energy analysts debated when we’d reach “peak oil” or run out of the stuff. Recently, some analysts have wondered when the demand for Alberta’s crude will dwindle, replaced by alternative — greener — sources of energy. Others study how a balance could be achieved and how the transition could occur.

Respected Calgary-based energy economist and investment strategist Peter Tertzakian foresees demand for oil returning after social distancing ends, but a “bruised global economy with soft oil demand is a foregone conclusion.”

Travel and commuting habits, he contends, may have forever changed because of the pandemic.

And Tertzakian anticipates an acceleration of the renewable energy transition.

“I think it’s going to happen. I support it,” he said.

“But that should not be confused with the idea of putting the oil and gas industry here to bed.”

Morgan Bazilian, a professor of public policy at the Colorado School of Mines and the director of the Payne Institute, which researches public policy on earth resources, energy and the environment, says that the collapse in oil prices and the decline in its demand triggered by the pandemic highlights the need for Alberta to diversify its economy.

Bazilian believes government stimulus packages aimed at kick starting the economy in the wake of the global pandemic need to be balanced between fossil fuels and renewable energy.

“But simply saying that we will move all the stimulus money on the energy sector to change and become low-carbon right away is unlikely to be the wisest use of the … stimulus money,” he added.

The pandemic and the economic fracture it triggered have revealed that there’s no “going back to business as usual,” predicts Severson-Baker, the Alberta regional director for Pembina.

“It’ll be a long, slow recovery, if it ever recovers fully,” for Alberta’s energy industry, Severson-Baker added.

“And it’ll be immediately followed by another decline in demand as a result of the world responding to the challenge of climate change.”

If change is upon us, the question becomes, how to deal with change the right way.

Academics have studied historical energy transitions: what worked, and what didn’t. They have identified some potential roads, and some potential roadblocks, ahead.

Possible paths

Writing last May in the prestigious journal Nature, several respected energy analysts, including the above mentioned Bazilian, described four possible paths to a low-carbon future.

In the first scenario — what they call the Big Green Deal — government policies, investment and global co-operation accelerate a rapid decarbonization. Governments across the world spend billions on renewable energy, and financial markets divest themselves of fossil-fuel assets, reallocating to low-carbon investments.

In the second imagined future — Technology Breakthrough — significant technological achievements allow renewable energy to displace fossil fuels, mitigating climate change.

In the third, somewhat dystopian future — Dirty Nationalism — populist governments protect the fossil fuel industries in their jurisdictions, fragmenting the global energy market and slowing the transition to a low-carbon economy.

In the final predicted future — Muddling On — the status quo persists. Fossil fuels remain the world’s main energy source. Renewable energy claims a share of the energy mix as its costs decline, but not enough to mitigate climate change.

Bazilian, believes the four models still hold up even in a post-pandemic world, adding that the “dirty nationalism” model was most closely aligned with the pre-pandemic situation where Saudi Arabia and Russia waged war over oil prices.

Tertzakian, who has written two books about energy transition, stresses that Alberta is already transforming its energy system, pointing out that the province is moving to mothball coal-fired power plants by 2030.

The long-time energy watcher supports diversifying Alberta’s economy and increasing renewable energy use. But he wonders what will replace the economic benefits of the oil industry.

Canada remains, after all, the fourth largest producer and fourth largest exporter of oil in the world. In 2018, oil and gas extraction alone accounted for more than seven per cent of Canada’s total gross domestic product (GDP), and it is our largest export.

“The reality is that the bulk of our oil and gas, the vast majority of it is exported and used elsewhere, for which we have substantial economic activity. So merely transitioning to renewables is not going to backfill that economic activity,” Tertzakian said.

A balanced approach

Bazilian says it’s important for any energy transition strategy to take care of the people who lose jobs in the planned switch from, for example, coal-fired power plants to renewable power, such as wind-powered turbines.

“You have to think about how it affects society from a social perspective,” he cautioned.

The speed of change must be handled carefully as well.

“Pace of change could really have some very negative connotations for citizens … the poor and the marginalized will suffer even more.”

So how to support both change and people?

Part of Alberta’s plan to reduce its carbon emissions could begin with the existing oil and gas industry.

The Pembina Institute’s Severson-Baker wants the federal government to invest stimulus money in carbon capture and storage and reducing methane emissions from upstream oil and gas production.

The energy industry, for its part, says any federal money should also help pay for the reclamation of inactive and orphan wells, creating jobs for out-of-work oil service workers.

Tertzakian expects some of the coming stimulus spending will be directed into renewable energy, such as wind and solar, and into energy efficiency retrofits. But again, he cautions that, in the long run, it won’t be enough to replace the economic activity generated by Alberta’s oil and gas industry.

Tertzakian suggests turning to other natural resources, including forestry and agriculture.

Alberta also has the advantage of relatively low electricity rates that could power newer industries, such as manufacturing and high-tech.

“Now we have the opportunity to use what we have under our feet and around us to create an economy that is more resilient,” he said.

But when you discuss jobs, livelihoods and people, you run into political territory.

The politics of transition

The CBC News Road Ahead 2020 poll found that, just as the economic impact of COVID-19 was hitting, 54 per cent of Albertans believed oil and gas companies have too much say in Alberta politics.

Some longtime political watchers say that, even before the coronavirus crisis began, the current provincial government was out of step with Albertans’ hopes for energy diversification.

“The government is not, I think, listening to the public on these matters,” said Duane Bratt, the head of the department of economics, justice, and policy studies at Mount Royal University.

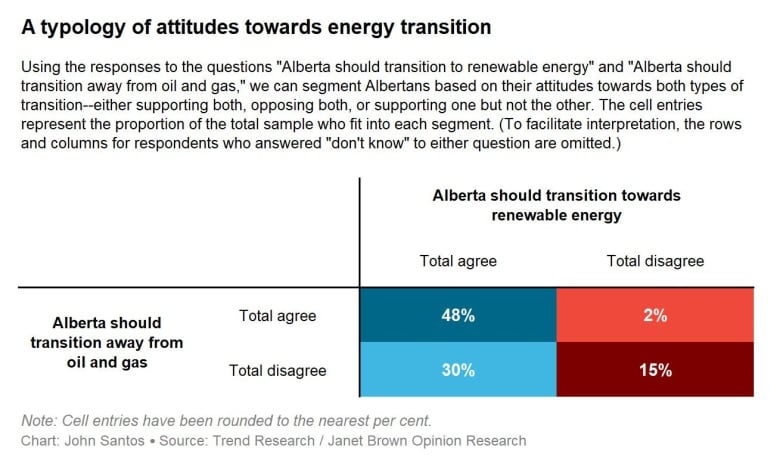

Taking a closer look at the polling data, we can break down Albertans based on their attitudes toward both types of energy transition. Almost half (48 per cent) agree with both increasing renewable energy and decreasing oil and gas production. One in three (30 per cent) support more renewables but don’t want to move away from oil and gas.

Contrast that with only 16 per cent of Albertans who are opposed to both types of transition. And a mere two per cent who hold the curious position of wanting less oil and gas but not wanting more renewable energy sources.

So, the debate isn’t about whether Alberta needs more renewable energy. The argument in Albertans’ minds is about the extent to which oil and gas remains a part of the province’s future.

These divergent Alberta opinions on what exactly our next moves should be are something the provincial (and federal) government must grapple with in a post-pandemic economic reality.

Certainly, there are efforts already underway in Alberta to transition toward green energy.

A spokesperson for the province’s minister of energy points out that Alberta already supports renewable energy projects, such as the country’s largest solar energy project near Vulcan, south of Calgary.

But current circumstances could force the UCP to accelerate economic diversification and energy transition, especially if demand for Alberta oil remains soft.

Tertzakian thinks economics will ultimately underpin politics.

He predicts the UCP will definitely be talking more about diversification in the expected anemic economy that follows the coronavirus.

“I don’t think it’s lost on them,” he said.

Methodology:

The CBC News random survey of 1,200 Albertans was conducted using a hybrid method between March 2 and March 18, 2020, by Edmonton-based Trend Research under the direction of Janet Brown Opinion Research. The sample is representative along regional, age and gender factors. The margin of error is +/- 2.8 percentage points, 19 times out of 20. For subsets, the margin of error is larger.

The survey used a hybrid methodology that involved contacting survey respondents by telephone and giving them the option of completing the survey at that time, at another more convenient time, or receiving an email link and completing the survey online. Trend Research contacted people using a random list of numbers, consisting of half land lines and half cellphone numbers. Telephone numbers were dialled up to five times at five different times of day before another telephone number was added to the sample. The response rate among valid numbers (i.e. residential and personal) was 13.2 per cent.