Against a common foe, nations around the world go their own way on pandemic

When Queen Elizabeth recently broadcast a message of reassurance to the British people in the age of COVID-19, not surprisingly perhaps, she invoked that old wartime spirit many Britons still relate to.

She referenced her own experiences during the Second World War and a broadcast she made from Windsor Castle as a young princess to children separated from their families.

But the Queen also implied that the crisis facing the world today was a little less lonely for nation states.

“While we have faced challenges before, this one is different,” she said. “This time we join with all nations across the globe in a common endeavour.”

It hasn’t often felt like it, though.

U.S. President Donald Trump’s “America First” rings loud and clear with, among other things, threats to withhold funding from the World Health Organization.

The European Union faces an existential crisis as it struggles to agree on acts of solidarity for its most stricken member states.

And all the while the world’s strongmen are seizing upon the chaos to consolidate their power further.

Taking care of their own

Individual countries may indeed be toiling against a common foe in the form of the virus, but the picture of an international community working together and offering a co-ordinated response remains very much a work in progress.

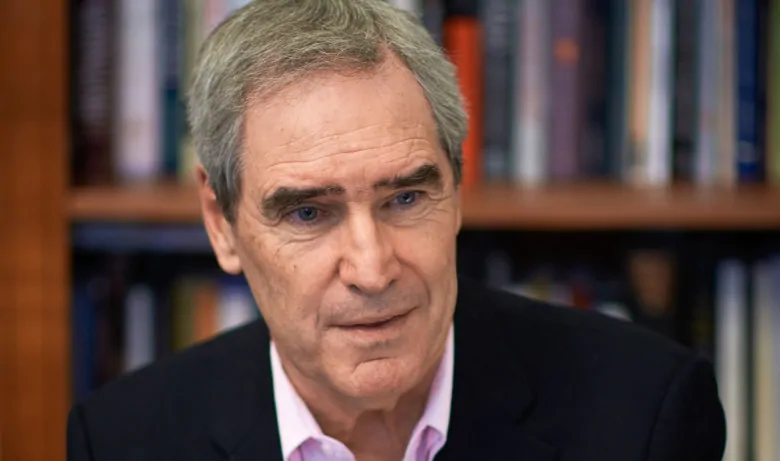

“The pandemic is laying bare a truth about the international global political system that you can never underestimate, which is that this is an order of sovereign states,” said Canadian academic and former federal Liberal opposition leader Michael Ignatieff, who is now the president of Central European University in Budapest.

“And when really bad trouble hits, every national political system draws up the drawbridge, closes frontiers, shuts down and takes care of its own. This is just a hard fact of the world we’re in.”

Igantieff was speaking from a town near Budapest not long after the Hungarian Prime Minister, Victor Orban, had himself awarded the power to rule by decree because of the coronavirus crisis but without a time limit.

The global pandemic has swung wide open the closets where world dictators keep their not-so-secret skeletons.

Amnesty International recently condemned Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, for example, for threatening that those opposing coronavirus directives could be shot dead.

4 hours’ notice for lockdown

“People like myself have been writing about [injustices] for years,” said the Indian writer Arundhati Roy in a Skype interview from her home in New Delhi.

“But it was as if it was a chemical experiment in which what is hidden suddenly came to light and you just saw it visually: the shamefulness of the society.”

She was describing the latest round of misery unleashed on India’s poor when Prime Minister Narendra Modi ordered a nationwide lockdown in a country of 1.3 billion people with just four hours’ notice.

Manageable perhaps, for the upper and middle classes able to retreat to comfortable homes, but for millions of migrant workers far from their villages or living crammed in slums and shanty-towns it was a disaster.

“You had police brutalizing them, beating them up,” said Roy. “In some places they were caught and sprayed with disinfecting chemicals.”

She also accuses Modi and his Hindu nationalist government of quite deliberately using the pandemic to stigmatize the already marginalized Muslim community.

“One of the greatest crises that’s faced any of us, certainly in the modern Western world, comes at a time where the most toxic, low-IQ, totalitarian men are in power,” said Roy, citing Trump, Modi and Orban in that order.

U.S. global leadership ‘over’

There has been much written in recent years, particularly in the European media, about the absence of U.S. leadership on the world stage since the election of Trump in 2016.

Ignatieff believes the notion of U.S. global leadership is “over” for the time being, even though he’s clearly uncomfortable with being drawn into criticism of the Trump administration’s handling of the pandemic given the vast challenges he says it brings with it.

“There is no substitute for competent national government,” he says. “And it goes against the idea that what we actually need is more global governance.”

WATCH | 3M strikes deal to keep sending masks to Canada after White House halts exports

But what about the existing mechanisms of global governance?

This week some 90 former presidents and prime ministers, including Britain’s John Major, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, and Canada’s Paul Martin, appealed to G20 leaders to spearhead a co-ordinated response to the pandemic.

United Nations agencies including the World Health Organization continue to mobilize in the fight against the pandemic across the globe, but the UN Security Council itself has been largely missing in action.

Back in 2014 the Security Council sent a strong message during the Ebola crisis afflicting West Africa by adopting a resolution declaring it a “threat to international peace and security.”

There has been no such declaration on the coronavirus even though it has wrapped its way around the globe.

“Leadership requires a recognition that you can’t abandon the rest of the world in this process, not only because it’s a humanitarian imperative, but also because it’s self-serving,” said the former Canadian politician and diplomat Stephen Lewis.

“If I can be crass: Unless this virus is defeated everywhere, it will come back.”

‘Nail in the coffin’ of EU?

Lewis is a former Canadian ambassador to the UN. He also served a term as the UN’s special envoy for HIV/AIDS in Africa, where his Stephen Lewis Foundation remains active.

“In a place like South Africa you have 7.7 million people with HIV, and three million of them are not in treatment,” he said.

“So they’re not receiving anti-retroviral drugs. It means that their immune systems are probably fragile and susceptible to a thrashing from the coronavirus.”

One bellwether in terms of the multilateral order’s health, he says, is whether or not countries respond to UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres’s appeal for $2 billion US to tackle the pandemic in poorer countries.

Analysts point to the European Union as a cautionary tale when it comes to solidarity even amongst those countries bound in more formal unions.

“It could be one of the nails in the coffin of the European Union,” said Josef Janning of Germany’s Council on Foreign Relations when asked about the impact of the coronavirus crisis.

“When our reflexes are tested, the reflex is national,” he said, pointing to Germany’s early decision to ban the export of medical equipment to other EU countries during the early stage of the pandemic, contrary to EU principle.

Germany has since taken some of Italy’s most critical medical cases to its own hospitals in a bid to ease the pressure there.

But Janning says the real test will come after the worst of the pandemic is over, when EU countries will have to agree on financial assistance to countries most in need.

This week, EU finance ministers agreed on a rescue package worth some $500 billion. But it is short of what many analysts believe will be needed to kick-start the European economy.

And the ministers did not agree on proposals for a joint-borrowing instrument proposed by Italy and Spain.

Lasting change?

One thing many nations afflicted by the pandemic share, not just in Europe but around the world, is a daily or weekly ritual where people open their windows or come out onto their doorsteps to bang pots, ring bells or applaud for the front-line health care workers battling the virus under such enormous pressure.

It is a moving expression of solidarity. But when all is said and done, will it leave behind any meaningful change in terms of the way societies value those health care workers or order society?

Janning doesn’t think so.

“Nor will it lead to a de-globalization, as some people now believe it will. I think we will all be longing to go back to where we were before.”

WATCH | Queen urges unity, strength in special COVID-19 address

Lewis thinks the pandemic has exposed weaknesses in the established ways.

“There is a very strong feeling, I think, in many countries now that the existing systems, the old systems, just have not prepared us for this and haven’t been working,” he said.

He doesn’t believe that means radical change, like an end to capitalism.

“On the other hand, what is happening now has never happened before historically,” he said. “And it gives all of us a chance to create something new.”

Ignatieff is less confident.

“We all come through these crises thinking everything will be totally different on the other side,” said Michael Ignatieff. “I just think we don’t know.

Roy has a more philosophical take.

“It’s as if there is no present,” said Roy. “There is a past and there’s an unfolding future that we don’t know. The present is an artificial bubble right now.”

All the more reason to pay attention to it — and not just at home.