The long journey to safety: Northern women travel farthest to access domestic violence shelters

This story is part of Stopping Domestic Violence, a CBC News series looking at the crisis of intimate partner violence in Canada and what can be done to end it.

It was the first and only time Ann Kasook attempted to run away.

She still feels shaken when she talks about that frigid winter night in Inuvik, N.W.T., in the early 1970s. Kasook was 20 years old.

“I was always told if I ever ran away, he would kill me,” said Kasook, who said she experienced verbal and physical abuse in her marriage for decades.

In the early hours of the morning, she fled her home with two of her children — one on her back and the other on foot — fearing her sleeping husband would wake and become violent.

She set out for a family member’s home only to find no one there.

“I felt so alone. I felt so lost. I had nowhere else to go so I had to go home.”

At that time, there was no women’s shelter in Inuvik, though there is one there now.

“It’s hard to explain the kind of fear that you have. It was just something that I had to live with,” Kasook said. Her husband died two years ago.

“That abuse still happens [to other women],” she said.

Nearly 50 years later, women across the North still don’t have the equal access to domestic violence shelters compared with women elsewhere in Canada.

Highest rates of intimate partner violence

Rates of intimate partner violence in the territories are among the highest in the country.

In 2018, there were eight intimate partner homicides in the three territories. The rate is nearly 30 times the rate for the rest of Canada, according to Statistics Canada’s Homicide Survey.

A lack of housing, stress from poverty, colonization and intergenerational trauma from residential schools contribute to the higher rates of violence in the North, says a report on intimate partner violence in the territories from the International Journal of Circumpolar Health.

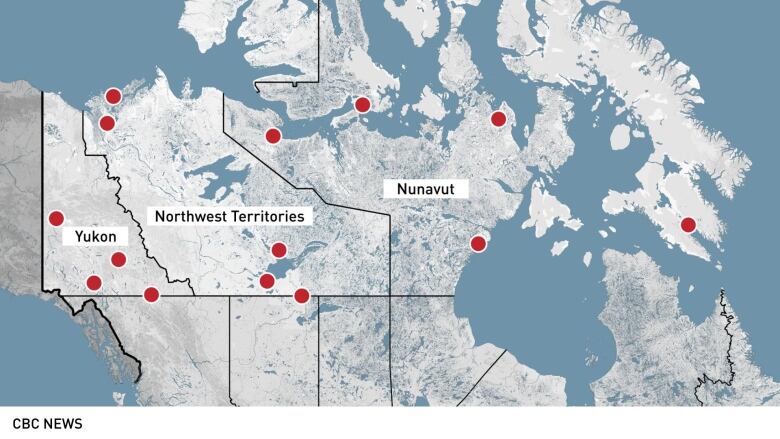

Across Nunavut, Northwest Territories and Yukon, there is a total of 14 family violence shelters. According to an exclusive analysis by CBC News based on 2016 Census Data, one in three people in the territories live more than 100 kilometres away from a domestic violence shelter.

By contrast, just one per cent of Canada’s population lives more than 100 kilometres from a shelter.

“We’ve had women who have snowmobiled out of communities and had a family member meet them on the highway and bring them out to a shelter,” said Lyda Fuller, executive director of the YWCA NWT, which operates two emergency shelters in the N.W.T.

In the winter, 14 of the Northwest Territories’ 33 communities are accessible only by plane or by driving on a winter road or ice highway. In the summer, the communities can be reached by plane or boat.

“So women are often put in precarious positions trying to escape,” said Fuller.

We’ve had women who have snowmobiled out of communities and had a family member meet them on the highway and bring them out to a shelter.– Lyda Fuller, executive director of the YWCA NWT

In the N.W.T., there’s funding available to help women and children access shelters in other communities. Women seeking shelter “frequently” fly in to Yellowknife from other communities, said Fuller.

But getting to safety is still difficult.

“It’s a lot of steps,” said Fuller. Once travel has been approved there’s waiting at the airport, the potential of delays due to weather, and the possibility a partner will find out the woman is fleeing, she added. Most N.W.T. airports don’t have security checkpoints like southern airports do.

“If this happens at midnight or two in the morning, then the helping agency might not be staffed at that point to do a flight out,” said Fuller. “So you might have to wait for the next day.”

In Nunavut, nearly all the communities are fly-in only.

More than half of that territory’s population is more than 100 kilometres away from a domestic violence shelter. People in Pond Inlet, Nunavut, are the farthest — roughly 1,175 kilometres from the nearest shelter.

Regardless, said Fuller, most women don’t want to leave their home communities at all.

High cost of operating a shelter

But creating more shelters isn’t simple.

“It hasn’t even been possible to protect the shelters we already have,” said Fuller, citing exorbitant operating costs.

One medium-sized shelter in the N.W.T., that operates 24 hours a day and has room for eight beds, costs roughly $600,000 annually to operate, said Fuller. What’s more, there are few buildings in the territory that are appropriate to house shelters.

The YWCA NWT is preparing to test out another option — safe houses. It’s heading up a $1-million pilot project to establish three safe houses in the N.W.T.’s shelter deserts.

A safe house is a designated safe place in a home, or a public space that is staffed when a person needs help.

Safe houses have been operating informally in some communities, but not on a consistent basis, said Fuller.

“That could save a life,” she said. Women wouldn’t have to leave their community, either.

‘For the first time … I could just breathe’

In a small Baptist Church in Aklavik, N.W.T., near the Peel River, Clarissa Gordon prays for her family and for strength.

She left an abusive relationship in Yellowknife two years ago, after giving birth to her second child.

While she was seven months pregnant, she said, her partner assaulted her in front of her six-year-old son.

“He was like, ‘Mom I got really scared. I thought he was going to kill you … I can’t lose you.’ And it was at that moment when … I was like, ‘What am I doing?'”

Gordon said in Yellowknife, she had a support network and access to a shelter if she had needed one. Only after she sought out counselling and treatment for her addictions was she ready to leave the relationship.

Gordon said women in Aklavik don’t have the same options for support.

The nearest shelter is in Inuvik, N.W.T., more than an hour drive over an ice road in the winter.

“I definitely see that as a barrier — having to get up and go,” said Gordon. She doesn’t know any women who have done that.

Reluctance to speak up

Gordon shares her experiences of intimate partner violence with teenage girls and women in her community whenever she can, one-on-one and at wellness gatherings.

She said women in the community are opening up to her in return.

But they remain reluctant to speak publicly about their experiences.

“Everybody knows everybody … so that really keeps people from opening up,” she said. Doing so can further isolate some women.

Along with more shelters, more education about intimate partner violence is critical to curbing the North’s high rates, said Gordon.

“Most of my life I thought this was normal. If we start with the younger generation we could really make a difference because they are our future.”

Gordon has since remarried and said she’s in a healthier relationship.

“For the first time, I feel like, I could just breathe,” she said.

If you need help and are in immediate danger, call 911. To find assistance in your area, visit sheltersafe.ca or http://endingviolencecanada.org/getting-help.