Day school claimants say lessons about trauma should have been learned from residential schools settlement

A new report examining the impacts of the 2006 Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) highlights some of the same issues arising with the current Indian Day School settlement claim process, say former students and their supporters.

The report, named “Lessons Learned: Survivor Perspectives,” released Thursday by the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, examines feedback gathered since 2018 from residential school survivors who participated in the IRSSA.

The report focuses on survivors’ experiences with the Common Experience Payment (CEP) and the Independent Assessment Process (IAP), as well as related health and funding initiatives and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

The 68-page document outlines survivors’ perspectives on the benefits and drawbacks of the process and suggests solutions.

‘I don’t think they learned anything’

Indian day schools operated separately from residential schools, so day school students were left out of the IRSSA. Day schools were operated by many of the same groups that ran residential schools, however. The Indian Day Schools Settlement was approved by the federal court last year and the claims application process opened in January.

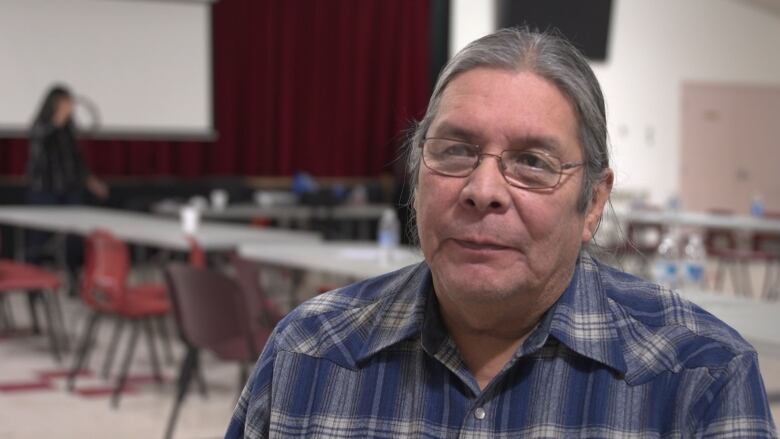

“I don’t think they learned anything, actually,” said Alan Knockwood, of Sipekne’katik First Nation in Nova Scotia.

Knockwood started his childhood education at a day school, spent three years at Shubenacadie Indian Residential School starting when he was nine, and then went back to day school until he was in Grade 7.

He completed the IAP process and recently filed a day school settlement claim. He said that while he hasn’t read the NCTR report yet, he participated in the feedback gathering process in 2018.

One of Knockwood’s frustrations with the IAP was the requirement for survivors to talk about their traumatic experiences over and over. In contrast, he said the day school settlement application took about an hour and a half, at his local health centre.

“The one for the Indian day school was a little easier,” he said.

“For the [IAP process], I had to make seven or eight trips to a lawyer’s office … I had to repeat and repeat and repeat.”

Under the day school settlement, there are five levels of compensation that former students can qualify for, each representing a greater severity of abuse or harm. Knockwood said he thought he would only qualify under the first, but as he got through the application, he was told that his experiences were classified under the third.

Despite the streamlined paper-based process, he said he takes issue with the lack of mental health and aftercare support for day school settlement claimants.

“I can walk in there and tell a story about my Indian day school and that’s that, but I’m going to go home and I’m going to relive it again, and I don’t know how many times that’s going to happen,” he said.

‘Spirit’ diluted by bureaucratic process

Ry Moran, director of the NCTR, said the Lessons Learned report is aimed at improving the lives of survivors and their families by informing policy makers, government agencies and any organizations looking to effectively work with, and for, Indigenous Peoples.

“I think the general call to action here is to always be very cautious and very cognizant about the communities that you serve,” said Moran.

The feedback revealed that survivors generally found the “spirit” of the initiative was diluted by the overly-bureaucratic and legally complex process, Moran said.

“Unfortunately, a survivor-focused, trauma-informed approach was sadly lacking in many elements of the IRSSA process,” the report’s conclusion reads.

While many survivors said they’d found some benefit to having their traumatic experiences “vindicated” through the TRC, some said the process may have done more harm than good. The most commonly identified complaints were related to re-victimization or re-traumatization during the process.

“The IRSSA process should have been designed from the outset to be trauma-informed, but was not,” the report reads.

‘A Kleenex and a hug’

Gibbet Stevens, a former Eskasoni Day School student herself and executive assistant to the community’s chief, has been helping hundreds of fellow students navigate the registration and applications forms.

“It’s constant. I barely have time to do my regular job,” she said.

She said she’s had to ask several people to stop filling out the forms, because she recognized they were being re-traumatized.

“It’s overwhelming, the stories I’ve heard … All I could do was offer them a Kleenex and a hug,” she said..

Debra Ginnish, another former student of the Eskasoni Day School, has been working with the Union of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq (UNSM) to help co-ordinate community-led support in the Unama’ki area, or Cape Breton Island.

When she took the position, Ginnish said she intended on working three days a week but addressing the needs of former students at the community level has since become a full time job.

“The need was there,” she said.

Ginnish said that while her contract is with the UNSM, she’s essentially become a liaison between community members and Gowling WLG.

Representatives from the law firm will be in Eskasoni First Nation Feb. 26 and 27, offering free legal advice and assistance with filling out the claim form. Ginnish said she’s hoping that the law firm’s team will have reviewed the NCTR’s report, and adopt a more trauma-informed approach.

“It would be good for them to learn the lessons from the residential school [process] and put some supports in place like they did back then,” she said.