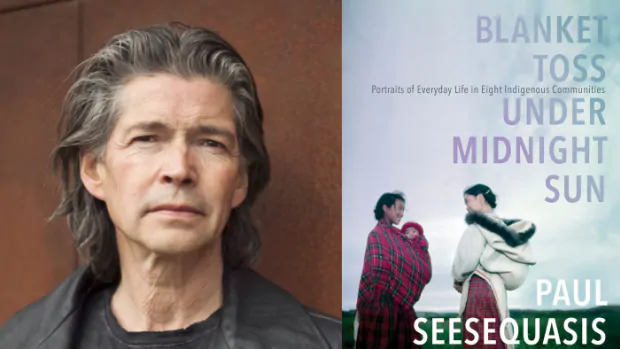

Why Paul Seesequasis wanted to reclaim everyday Indigeneity through archival images

After Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission report was released, Willow Cree writer, cultural activist and journalist Paul Seesequasis felt compelled to do something to contribute and understand what his mother, a residential school survivor, went through.

He began to collect and share never-before-published photos of Indigenous communities across North America, and learned the stories of those photographed. Blanket Toss Under Midnight Sun shares some of the most compelling images and stories from this project.

The Saskatoon-based Seesequasis spoke with Shelagh Rogers about how Blanket Toss Under Midnight Sun came to be.

Inspired by his mother

“This book began from a comment my mother made to me when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was happening. She is a residential school survivor. She felt that she wasn’t hearing anything on the news that reflected the strength of our families, our kinships and our relations with each other through the hardest of times.

This book began from a comment my mother made to me when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was happening.– Paul Seesequasis

“That piqued my interest. I started my research and delved into these photos. I began to post some of them online, just to see what the response would be. I had no idea it would evolve into what it is today.”

The power of the past generation

“I was looking for photos that reflected kinship, strength and families’ relationship with the land. It’s the idea that previous generations, even going through the hardest times of forced relocations or residential schools, had strength that enabled today’s resurgence of languages and culture of so many great artists, writers and filmmakers that we see today.

I was looking for photos that reflected kinship, strength and families’ relationship with the land.– Paul Seesequasis

“I really wanted to pay homage to that generation; photography became the medium to do it.”

Visual reclamation

“I discovered these images in public archives, libraries and museums across North America. The public response to these photos was actually quite shocking at first, but in a positive way.

“In a lot of cases, the photos were unnamed or they had the most generic of titles and archaic terminologies such as Two Indians in a Canoe, that kind of thing. As I began to post these photos, people began to recognize themselves or their family members in the images.

As I began to post these photos, people began to recognize themselves or their family members in the images.– Paul Seesequasis

“It began this process of visual reclamation, which I think was an important aspect of this whole project. It’s evolved to become this book and also into a travelling art exhibit.”

The evolution of everyday culture

“I hope these photos portray the fact that Indigenous cultures have always evolved and adapted. While images of Indigenous regalia and powwows are important, they’re not the extent of who we are as Indigenous people.

I hope these photos portray the fact that Indigenous cultures have always evolved and adapted.– Paul Seesequasis

“In selecting these photos I was looking for day-to-day things: people hunting and living off the land, people going to gatherings just dressed in their normal everyday clothing.

“I was very much trying to avoid that static ‘beads and feathers’ kind of framing you see through an outsider’s gaze.”

Paul Seesequasis’s comments have been edited for length and clarity.