Here's the backstory on this Inuvialuit parka left at an Edmonton thrift shop

Margaret Kanayok squinted her eyes scanning an image of a sealskin parka on Facebook.

If she could just touch it, and examine the stitch work, Kanayok said she could tell exactly who made it.

“When I saw it I said, ‘Oh that’s from Holman,'” said the 70-year-old Kanayok, who lives in Ulukhaktok, N.W.T., formerly called Holman, the community where the parka was made several decades ago.

“Holy, people still have them,” she said in surprise.

The parka that Kanayok is referring to appeared in a donation bin outside an Edmonton thrift shop earlier this week. Staff knew it was unique and from the Northwest Territories. Instead of selling the parka they put out a call for information on social media.

They were happy people working together enjoying the company of each other.– Margaret Kanayok

The tag on it reads “Holman, N.W.T. Handmade by Eskimos.”

The coat was commercially produced by the Holman Eskimo Co-operative likely in the 1960s and 1970s, said Kanayok.

“It’s [was] an income for the people. The only way they were making money [was] by sewing these items,” said Kanayok who worked at the Holman Eskimo Co-operative for more than 40 years and managed the craft store during that time.

“I tell you we made quite a bit of those parkas for people.”

Founded in 1961, the co-operative — located on Victoria Island in the Canadian Arctic — began commercially producing sealskin products for southern markets. Those products included everything from tapestries, to stuffed animals and parkas.

It was part of the movement to help the Inuit market and sell their traditional crafts and art.

“They used to buy thousands of sealskins each summer and send them out to be tanned and get them back to make all sorts of items,” she said.

“It makes them proud,” she said speaking about the women and men who made the parkas.

The co-op took orders and gave out patterns and supplies to local sewers, explained Kanayok. The seamstresses often came up with their own designs to dress the hems and the fur cuffs, she said.

Each sewer was paid for their work and skill.

“They were happy people working together enjoying the company of each other. I used to love that, seeing all the people talking and telling stories,” said Kanayok, who helped distribute the supplies and ship orders.

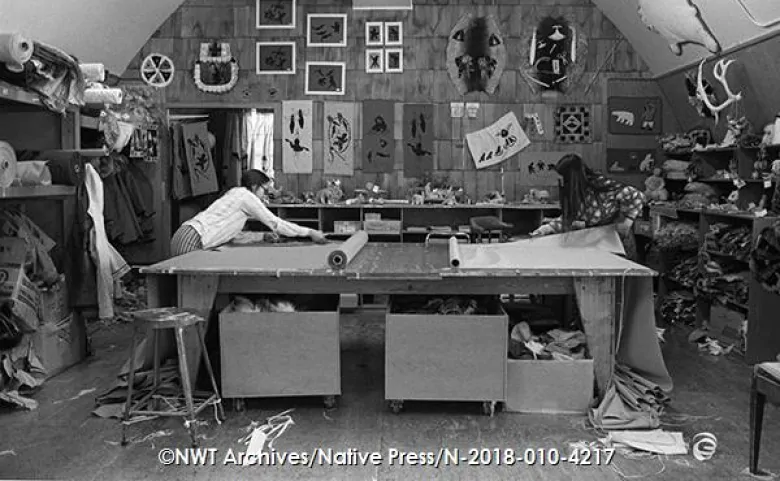

Calvin David Abrahamson, a former supervisor for arts and crafts development for the territorial government in the N.W.T., recalls that era well.

“A lot of people including Canadian artistic producers from Ottawa bought things from Holman Island,” said Abrahamson, who is nearly 90 years old. He describes seeing a “parka factory” that resembled a garage.

“It wasn’t anything famous,” he said.

He said the sealskin parka that showed up at an Edmonton Goodwill is likely valuable.

“Looks like it was well-done by a craftsman who knew what they were doing,” he said.

A similar sealskin parka is currently on display at the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre in Yellowknife and is part of the museum’s permanent collection.

‘Visually stunning and very warm’

The parka was designed for a man, made of two or more ring sealskins with wolverine fur trim and produced by the Holman Eskimo Co-operative in the 1960s, said Ryan Silke, the museum curator’s assistant.

“They are very visually stunning and very warm. There was an incredible demand for these things not only with northerners but with southern markets,” said Silke.

He said while the parka discovered in Edmonton is a great thrift store treasure, it is not a rare cultural relic.

“They are quite common,” he said.

It’s hard to say how many of the parkas were made during the 1960s and 1970s. The market for sealskin parkas cooled in the 1980s, said Silke.

Several have been offered to the museum over the last decade. He said government workers often bought the parkas and brought them south.

Only now, many of the parkas are resurfacing from people’s closets and basements.

“People want to find a home for them,” said Silke, who says unless the parka has a personal story behind it, it likely won’t end up in his museum.

“We have decided to preserve a couple of examples made by the co-op to tell the story of these co-operatives and how important they were economically in the communities.”