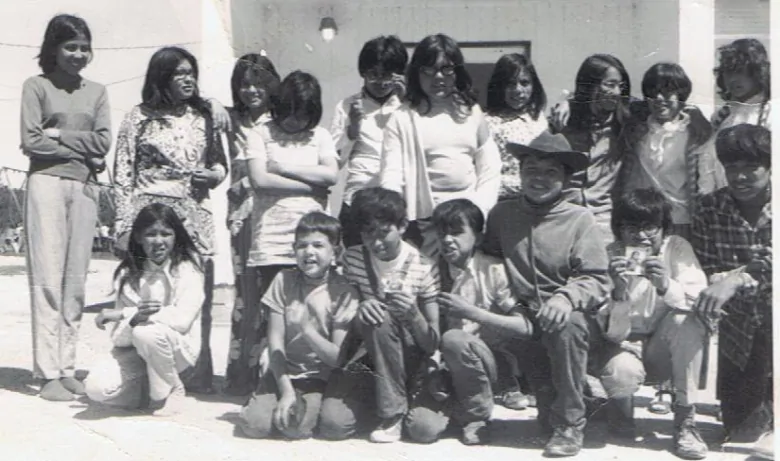

Children at Lake Manitoba Indian day school were strapped for speaking their language, say former students

Former students of the Lake Manitoba Indian day school, attended by the lead plaintiff of the class action lawsuit, describe it as a place where children spent a good deal of time praying and would get strapped for speaking their language.

“They didn’t really teach us about education,” said former student Russell Maytwayashing.

The Lake Manitoba school, also known as Dog Creek school, was attended by Garry McLean, who was the original lead plaintiff in the Indian day schools class action lawsuit. McLean died in February 2019 of cancer, a month before Canada announced a final settlement agreement had been reached.

McLean started the legal action regarding the forced attendance of Indigenous students at Indian day schools in 2009. It proposed a national class action lawsuit to seek compensation for the damages and abuses suffered by day school students, who were excluded from the $1.9 billion Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

Like residential schools, day schools aimed to assimilate Indigenous children while eradicating Indigenous languages and cultures, and often had religious affiliations to the Roman Catholic, United, Anglican, and other churches.

Russell Maytwayashing was a student at the Lake Manitoba day school from 1964 to 1967. He started attending the school when he was about six and said that McLean was at the school at the same time, although McLean was an older student.

In the 1960s, the day school had two classrooms. One room had Grades 1-3 and the other had Grades 4-6. The school was affiliated with the Roman Catholic church and was administered by the Grey Nuns.

“All we did was pray,” said Russell Maytwayashing, who is now an Ojibway language teacher at a Winnipeg high school.

“When we entered the school classroom, the school building. We prayed before we went out for recess, we prayed before we went for lunch and before we went home.”

He remembers being taught arithmetic, reading and writing. He also remembers the teachers being strict and students not being allowed to talk with each other during school hours.

“You had to comply with them whenever they spoke to you; we had to be on our guard all the time,” he said.

Aside from talking in class, he said the biggest cause for punishment inside the classroom was for speaking Saulteaux/Anishinaabemowin.

“If you were caught speaking in class, you would be called up to the front, and then the nun would give you a strap,” said Russell Maytwayashing.

He said being punished for speaking the language has had a long lasting impact on the people in the community.

“No one seemed to take pride in who they are and acknowledge our identity,” he said.

After he finished Grade 6 at the day school, he went to the Assiniboia Indian Residential School in Winnipeg for three years.

2 weeks at day school

Robert Maytwayashing spent the early years of his life living in and going to schools in Winnipeg.

He doesn’t remember the exact age he was, but he guesses that he was about 12 when he attended the day school in Lake Manitoba in the early 1970s.

He recalls travelling home to Lake Manitoba First Nation so that his dad could trap muskrat, and during the spring, his parents enrolled him in the school.

He said he attended the school for only two weeks, but was sexually assaulted during that time by other students.

He said a group of older boys were bullying him since he was “the strange kid in town.” He said the boys wanted to see how big his penis was.

“A group of them jumped me and they held me down, and they pulled my pants down, that’s what happened,” he said.

Robert Maytwayashing said it took a long time for him to get over the humiliation that he felt from that experience.

“I carried that with me for a long time because I was assaulted. I was very wary and cautious after that.”

He said because the amount of time that he spent at the school was brief, he is unsure of whether he will be eligible for a settlement claim.

Impacts carry forward

Margaret Swan also attended the school in the 1970s.

She said there was all kinds of abuse in the school — physical, sexual, emotional — and that students were often belittled.

Swan was part of the class action lawsuit with McLean and became the lead plaintiff after his death.

“Garry involved me a lot behind the scenes because we were both part of this,” said Swan.

Swan said McLean helped her file her affidavit and helped her to work through the emotions brought up by recounting her experience.

“I did a lot of crying and it was at that point I realized I, too, carried so much trauma from that past and I didn’t even realize that until I was forced to talk about the physical abuse.”

Swan attended the schools for five years and said the schools have had an impact on generations of her family.

“It was not even three years ago that I started to deal with my own issues from back then and how it related to some of the things I could have done better as a parent, as a human being, as a mom and sister,” said Swan.