Astronomers believe we could be in for a rare meteor storm

There’s a chance a rare meteor “storm” will occur Thursday night, and eastern Canada might be able to catch it.

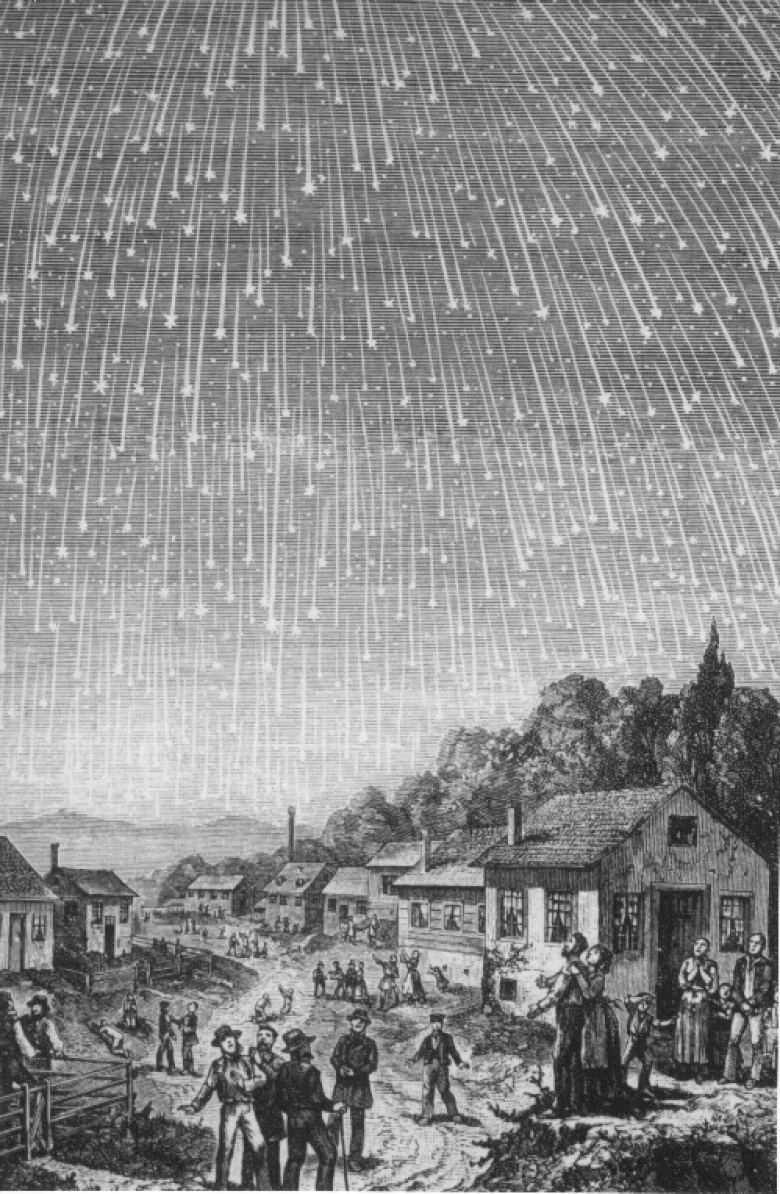

Meteor storms can be defined as a substantially higher-than-normal outbursts of meteors entering our atmosphere, and occur when Earth sweeps through a dense cloud of leftover cometary debris.

These events can produce several hundred meteors per second. In 1833, a storm associated with the Leonid meteor shower produced 13,000 meteors per hour at its peak.

While the annual alpha Monocerotids is forecast to produce an outburst this year, it is not expected to be anywhere close to that rare 1833 event. But it will still be something to see — if the weather co-operates.

“We might see a meteor, and then a few seconds another meteor, and then two more meteors,” said Peter Brown, professor and Canada research chair at Western University’s department of physics and astronomy.

However, there are a few things that make this potential outburst unpredictable, particularly for us here in Canada.

One is that the radiant, or the area from which the meteors appear to originate — the constellation Monoceros, which is where the shower gets its name — will be low in the south, to the lower left of the very familiar constellation Orion.

The other is that, unlike with many meteor showers, it’s not known which comet is responsible for this one, which makes it more difficult to understand where much of the debris is and how spread out it is.

As well, there’s the good old Canadian fall weather: it’s typically cloudy this time of year.

And finally, it’s how brief the shower will be: the peak is between just 15 and 20 minutes.

“Hollywood always has this view of meteor showers as these things that happen in 20 minutes and it’s all over,” Brown said. “And every other meteor shower is not like that — except this one … and that’s rare.”

Up for debate

The potential storm is making headlines due to the prediction by astronomers and meteor experts Peter Jenniskens and Esko Lyytinen, recently published on the site Meteor News, that there’s the potential for this year’s shower to produce between 100 meteors an hour and upwards of 1,000 an hour.

To put that in perspective, two of the year’s best meteor showers — the Perseids in August and the Geminids in December — can produce, at their peak, about 100 to 150 meteors per hour in a dark-sky location.

The alpha Monocerotids, however, which occur at this time of year, typically only produce just a few an hour.

The last outburst, in 1995, produced roughly 400 an hour.

Jenniskens and Lyytinen made the forecast for the burst because the geometry — the location of Earth, the location of the debris field — is believed to be roughly the same as it was in 1995.

However, because there are a lot of unknowns, some astronomers believe the outburst will produce far fewer than their prediction.

“This year is the best geometry encounter since 1995,” Brown said. “The problem is the exact encounter geometry depends on really knowing the orbit of the meteoroids as well, and we don’t know them that precisely. So within that uncertainty, it could be that we just glance the trail or miss it — in which case nothing happens — to we plow right through the middle.”

If Earth does plow right through it, that means we’ll get an intense shower for 15 or 20 minutes, perhaps seeing five or six meteors every minute.

“Even if everything works out well, you’d see in 30 minutes to 40 minutes as many meteors as you’d see during the peak of the Perseids when the radiant is right overhead,” Brown said. “It’ll be obvious that something is going on.”

But even in the best-case scenario, with a perfectly clear sky, there’s still that narrow window.

When and where

And even then, the entire country won’t be privy to the show.

Anyone west of roughly Saskatoon won’t be able to see it.

The peak will begin at roughly 4:50 a.m. UTC, which would be 11:50 p.m. Eastern Time; 10:50 Central; 12:50 a.m. Atlantic; and 1:20 a.m. Newfoundland Time.

If you’re clouded out, you can always try watching online (providing there are clear skies). The Virtual Telescope Project will attempt to catch the outburst and cover it live.

If we do indeed see any, these meteors are fast-moving, and there could be “grazers” — meteors that come in at a shallow angle. These meteors are going through more atmosphere, producing long tails before finally burning up entirely.

Whether or not it puts on a show, astronomers will be able to learn more about this strange annual meteor shower.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that astronomers began to realize this was an annual meteor shower. And it wasn’t until 1995 that it became clear the comet responsible was unknown, and highly unusual in its orbit.

But for the general public, it’s yet another reminder that there’s a lot going on in our solar system and that it’s not always so predictable.

“It’s neat. I think people should go out and take a look,” Brown said. “You never know.”