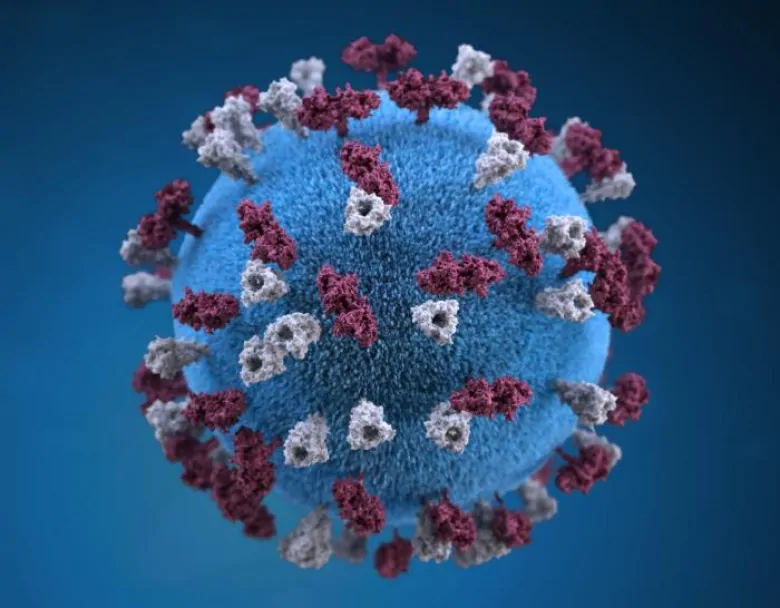

Measles limits immune system's ability to fight off other infections, studies suggest

The measles virus has not only made a devastating resurgence worldwide, but it may also cripple the immune system’s ability to fight off other infections in the long term, two new studies suggest.

The highly contagious measles virus causes coughing, rashes and fever and can lead to serious complications. Last month, the World Health Organization said reported cases rose 300 per cent globally in the first three months of this year compared with same period in 2018 .

A two-dose vaccine has helped to slash measles cases since 2000, saving an estimated 21.1 million lives between 2000 and 2017, WHO said.

But the rise of anti-vaccination campaigns, non-vaccinating religious communities and other factors have led to outbreaks causing tens of thousands infections in Congo, Madagascar, the Philippines, Sudan, Thailand and Ukraine, among other countries, according to WHO.

Now researchers say measles vaccination not only controls measles, but it also protects the immune system from losing its ability to suppress other infections.

Stephen Elledge, a geneticist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and a co-author of one of the papers presenting evidence that the measles virus destroys part of the immune system, compared the damage to a head injury.

“You can be in an accident and you could have a head injury and you could lose your memory,” Elledge said. “The measles virus is like an accident for your immune system. It loses its memory. But we know how to deal and prevent a lot of these head injuries. It’s called seatbelts and vaccines are like a seatbelt for your immune system.”

Normally, when we’re exposed to an infection, the immune system’s antibody factory kicks into high gear to recognize, remember and defend against a pathogen if it comes along again by making lots of fighter cells.

But the two teams of researchers found that after measles infection, the fighter cells, called B cells, seemed to be wiped out for months or even years. Without them, the body is vulnerable to pathogens such as the influenza virus or pneumococcal bacteria that cause ear infections.

The experiments were only possible because 77 families of unvaccinated children in the Netherlands agreed to donate blood samples after they were infected in a measles outbreak in 2013. Researchers compared those samples to ones from healthy volunteers.

In infants who were not vaccinated and caught measles, the level of antibodies that could fight off other infections plunged. That didn’t happen in infants who were vaccinated against measles.

At the same time, Colin Russell, a professor of applied evolutionary biology at the Academic Medical Center at the University of Amsterdam, and his team looked at how the immune system loses its ability to fight other infections using another laboratory method.

Together, the studies offer independent and complementary pieces of evidence of how the immune system can lose its memory, Russell said.

Consequence can last years

Russell said in 10 per cent of the unvaccinated children, one part of the immune system found in the bone marrow — the naïve component — was completely reset. Their immune system reverted to a naïve, infant-like state.

What’s more, the degree of suppression was comparable to taking powerful, immunosuppressive drugs for organ transplants.

“The immune consequence for measles can last for years and all of this really just goes to underscore the importance of measles vaccination because all of these things are entirely preventable just by getting your kids vaccinated,” Russell said.

Dr. Manish Sadarangani, who directs the Vaccine Evaluation Centre at BC Children’s Hospital, wasn’t involved in the research, but called it fascinating and important work that uses cutting-edge techniques to study how the measles virus affects the human immune system.

Previously, evidence on how measles infection suppresses the immune system was just circumstantial, Sadarangani said.

Sadarangani called it “incredible” how measles infection profoundly affects parts of the immune system similar to powerful immunosuppressive drugs.

Sadarangani said when he speaks to parents who have concerns about measles, some ask about complications that mostly occur in the few days after measles infections.

“This adds a whole new dimension,” he said. “It makes the argument to my mind of vaccinating much more powerful because you’re now preventing not just measles but all of these knock-on complications that may be related to measles.”

The researchers said limitations of their work include the small number of subjects from just one population. Some of the authors also serve as advisers to vaccine makers.