Attempted sextortion leads to call for stricter phone porting rules

When Randall Baran-Chong received a notification on his smartphone late one night last week indicating the device was no longer in service, it was the first sign of trouble.

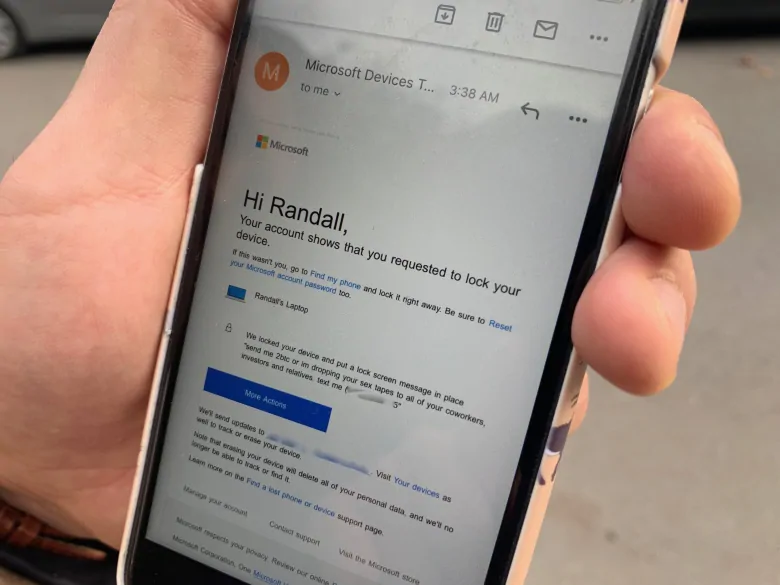

Around 3:30 a.m., emails started appearing in his inbox, warning him of changes made to his Microsoft account. His password had been reset and his email address removed as a verification method.

“I knew things were about to go badly,” he said.

In the hours that followed, the 33-year-old Toronto businessman says someone locked down his laptop, purchased an Xbox video game gift card using Baran-Chong’s credit card, accessed his personal files and threatened him with extortion — all because someone was able to steal his cellphone number.

It had been fraudulently “ported” — transferred from his Rogers account to a Bell prepaid customer. The fraudster then seems to have used a password retrieval process involving text message verification to gain access to Baran-Chong’s Microsoft account, tied to his computer’s operating system and a cloud-based file backup service.

Sextortion threat

In another message, the fraudster threatened to take the attack a step further: send two bitcoins (about $25,000 at the time) “or I’m dropping your sex tapes to all of your coworkers, investors and relatives.”

Baran-Chong had several years’ worth of photos and videos saved in his cloud account. Among them were clips of him engaging in sex acts with women. (He says the sex was consensual and the women involved have been told of the breach.)

“I cried at 3:30 in the morning,” he said, “because I was like ‘why is this happening to me?'”

Baran-Chong rushed to contact his mobile carrier, but was only able to regain his number the following day. By then, it had become clear to him the fraudster had looked through his files — and thoroughly.

He received another threatening message, with images attached this time: a scan of his passport — which he had saved when applying for a travel visa — and screen captures of the intimate videos the fraudster was threatening to release.

“It’s a violation,” Baran-Chong told CBC in his Toronto home. “I see it the same way as being held hostage in the middle of Yonge-Dundas Square with a gun to my head.”

How the scheme works

Canadian police have warned the public about phone porting fraud before. Similar schemes were apparently used to tweet offensive, unauthorized messages from Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey’s account and to publish naked photos of pop star Justin Bieber on the Instagram page of his ex-girlfriend, fellow performer Selena Gomez.

Baran-Chong’s ordeal, though, highlights how lesser-known users can fall victim and see their password-protected profiles unlocked with just a mobile number.

“The proper mechanisms have not been put in place to protect consumers and everyday people,” said Ritesh Kotak, a Toronto-based cybersecurity expert.

The premise is simple: a scammer identifies a victim’s cellphone number and provider, then tricks the company into porting the number to the fraudster’s device.

Many online services allow users to reset their password using a two-step process involving a code sent by text message to a registered number. With this scheme, the code is intercepted and the password is changed, opening the door for criminals to steal personal data.

Until the carriers “fix” porting, there remains “a gap that’s going to be exploited by hackers for nefarious reasons,” Kotak warned.

Porting rules

In Canada, the CRTC established wireless number portability in 2007, streamlining the process to keep the same number when switching carriers. All service providers must follow the same guidelines, which are administered by the Canadian Wireless Telecommunications Association (CWTA), an industry body.

In Baran-Chong’s case, “the fraudster had all of the required information to port the telephone number and the automated system processed the number transfer in compliance with the CWTA rules,” Bell spokesperson Nathan Gibson told CBC.

According to details posted on the CWTA’s website, a user can request to have a mobile number ported to another device with as little information as the number itself and the customer’s account number. CBC’s Marketplace revealed earlier this year that such details can sometimes be obtained by conning a customer service representative.

Carriers update guidelines when “fraudsters find a way to cheat the system,” Robert Ghiz, the CWTA’s president and CEO, said in an interview. “Once you find a way to prevent them from going about it one way, then they try to find another way, so also it’s up to us to continuously evolve.”

As for Baran-Chong, it wasn’t even the first time he was targeted. He said his number was briefly stolen in June, but that no other data had been accessed then.

WATCH | Randall Baran-Chong says he felt violated after his cellphone number was stolen:

He said he added a four-digit PIN to his Rogers account after the first attack, but that the carrier didn’t provide any additional protection to prevent his number from being fraudulently ported again. The second time, he said Rogers offered to contact him in the event someone tried to transfer his number in the future.

“I said ‘of course, that should be the norm. All of us should have that protection.'”

Rogers only offers the added security measure to victims of unauthorized porting or fraud.

Rogers apologizes

The company offered an apology for Baran-Chong’s “experience” in an email to CBC.

“We take protecting our customers’ personal information very seriously, and as fraudsters evolve their tactics, we work with other carriers to continually strengthen processes to prevent unauthorized porting,” Rogers spokesperson Sarah Schmidt said.

Rogers is rolling out a text message notification measure if there’s a request to port a customer’s number, but as it stands, Canadian cellphone users have limited options for safeguarding their number.

Meanwhile, Bell is considering a customer notification service “to further strengthen the porting process, while keeping the system as seamless as possible for customers,” Gibson said.

Baran-Chong suspects his attack was targeted — and carried out by a former acquaintance — but said “every single Canadian with a cellphone is at risk.”

The CRTC says it has received three complaints related to phone porting since the start of this year.

‘It’s going to hang over my head’

Baran-Chong is demanding stricter regulations to prevent scammers from porting other customers’ phone numbers and using it to steal data.

“There’s not enough protection for our digital selves,” he said.

He reported the incident to police, who are treating it as a case of attempted extortion. Toronto police confirmed to CBC that the force is investigating, but that the probe is only “in its infancy.”

Baran-Chong said he hasn’t paid the ransom to prevent his intimate videos from being released. They haven’t been sent to anyone he knows. But he fears they will be, one day.

“The problem is I live under the sword of Damocles, in a way,” he said. “It’s going to hang over my head for the rest of my life.”